The second of Webern's Five Canons, op.16:

This lullaby text, from a sixteenth-century engraving by Hieronymus Wierix, was copied by Coleridge during his visit to Germany with Wordsworth and published two years later, in 1801. Coleridge would publish an English translation, also below, in 1810.

quae tam dulcem somnum videt,

dormi, Jesu! blandule!

Si non dormis, Mater plorat,

inter fila cantans orat,

blande, veni, somnule.

Sleep, sweet babe! my cares beguiling:

Mother sits beside thee smiling;

sleep, my darling, tenderly!

If thou sleep not, mother mourneth,

singing as her wheel she turneth:

come, soft slumber, balmily!

Friday, 30 December 2011

Thursday, 29 December 2011

Christmas Music from Liszt and Schoenberg

We rightly tend to think of choral music at Christmas time, but there are instrumental gems, often little known, to be heard too. In a late studio recording, Vladimir Horowitz plays 'Ehemals' from Liszt's Weihnachtsbaum:

And here is Schoenberg's adorable Weihnachtsmusik, from the Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna. When I hear it, I fancy that it tells us as much about the composer as the Variations for Orchestra. The contrapuntal mastery cannot be gainsaid, not least that wondrous interpolation of Stille Nacht, nor the command of tonal relations, here most obviously between the tonic C major and its subdominant, F major. Nor, of course, should one or could one ignore the mastery of textural balance: think also of the Johann Strauss arrangements. What nevertheless comes across every bit as strongly is Schoenberg's profound humanity. Is this his Siegfried-Idyll?

And here is Schoenberg's adorable Weihnachtsmusik, from the Arnold Schoenberg Center in Vienna. When I hear it, I fancy that it tells us as much about the composer as the Variations for Orchestra. The contrapuntal mastery cannot be gainsaid, not least that wondrous interpolation of Stille Nacht, nor the command of tonal relations, here most obviously between the tonic C major and its subdominant, F major. Nor, of course, should one or could one ignore the mastery of textural balance: think also of the Johann Strauss arrangements. What nevertheless comes across every bit as strongly is Schoenberg's profound humanity. Is this his Siegfried-Idyll?

Wednesday, 28 December 2011

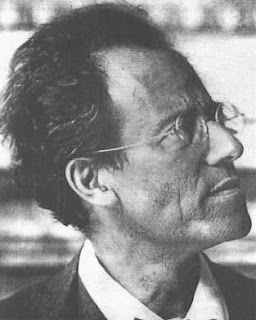

At the End of (another) Mahler Year...

... I find myself on a reasonably lengthy railway journey. Having foolishly packed books and my iPod in an inaccesible suitcase, more or less the only amusement - relatively speaking - available is my laptop. Or, of course, whatever I still can muster in my head. Any regular readers may recall a distinct lack of enthusiasm for this year's - and last year's - Mahler anniversaries. I shall not rehearse the arguments now, other than to say that a greater tribute would have been a period of silence; Mahler is a composer I love dearly, perhaps too dearly, but the last thing he needed was a further run of unnecessary performances. (Lorin Maazel... No, I shall stop myself there.) I decided a little earlier en route to set myself a logical puzzle. Not to recommend a favourite recorded version of each symphony, but something a little different: to select a favoured set, with no more than one performance per conductor. Trying to do the same with respect to orchestras proved too much. Doubtless I should change my mind tomorrow, but here are the results, with Amazon links for any who might be interested.

1: Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra/Rafael Kubelík

2: Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra/Otto Klemperer

3: London Symphony Orchestra/Jascha Horenstein

4: London Philharmonic Orchestra/Klaus Tennstedt

5: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Leonard Bernstein

6: WDR Symphony Orchestra, Cologne/Dmitri Mitropoulos

7: Staatskapelle Berlin/Daniel Barenboim

8: Staatskapelle Berlin/Pierre Boulez

Das Lied von der Erde: Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Bruno Walter

9: Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir John Barbirolli

10: Berlin Symphony Orchestra/Kurt Sanderling

Please feel free to comment/to tear apart, and/or to suggest alternative lists.

May next year bring fewer and superior Mahler performances...

Friday, 23 December 2011

OSJ/Lubbock - Handel, Messiah, 22 December 2011

Hall One, Kings Place

Hannah Davey (soprano)

Roderick Morris (counter-tenor)

John Pierce (tenor)

David Pike (baritone)

OSJ Voices (chorus master: Jeremy Jackman)

Orchestra of St John’s

John Lubbock (conductor)

This was a delight: very much a tonic to December blues. Time was when Hall One of Kings Place would have been considered risibly small for a performance of the Messiah – though time was when anywhere smaller than the Royal Albert Hall or even the Crystal Palace would have been. Monster Victorian performances from the likes of Sir Michael Costa are long gone, though we should do well to recall not only the popular enthusiasm they engendered but also their musical influence: Haydn, in London, heard a performance, which, if not Victorian, employed forces inconceivable today. It set him on the road to writing The Creation.

Back to Kings Place. This was a chamber performance, at least in terms of the orchestra, strings fewer than I have ever previously encountered: 3, 2, 2, 2, 1. That presents a few problems, not so much in terms of volume – even my knowledge of acoustics informs me that thirty first violins are not ten times as loud as three – but blend and tonal quality. (Indeed, one to a part, true chamber music, will lose the rough edges.) So there were occasions, especially when playing softly, when ensemble could prove a little rough. They should not, however, be exaggerated in importance, and should be balanced against considerable cultivation at other times. Vibrato was not eschewed, even if there were passages, more so in the First Part than later on, when more would have been welcome. Leader Richard Milone’s solo work was especially finely turned. And if there were occasions when John Lubbock indulged the contemporary fashion for abrupt endings to phrases – believe me, I have heard much, much worse – much of his characterisation of individual numbers proved both apt and refreshing. For instance, I do not recall hearing ‘He trusted in God that He would deliver Him’ performed with such anger, malice even: the great turba choruses of Bach’s St John Passion came to mind. Given that the words are those of the vicious mob, they who ‘laugh Him to scorn’, such a performance made excellent sense, imparting a greater narrative drive to a section of the oratorio that is not entirely without longueurs, whichever version is employed. (The present version did not, off the top of my head, correspond to any particular Handel performance, but worked well enough.)

Choral singing, from OSJ Voices, was excellent throughout. Forty-eight strong, according to the programme, this was by contemporary standards a fair-sized chorus, but it lacked little in agility, responding with alacrity to Lubbock’s keenness in numbers such as ‘And the glory of the Lord’. Weight was present where necessary too: indeed, the wholeheartedness to the closing choruses of the second and third parts was quite moving. (Almost everyone stood for the ‘Hallelujah’ Chorus. Two notable refuseniks were those who had chattered and disrupted with sweet-wrappers throughout. I shall remember their faces…) This, then, was a choral performance that would put many professional choirs to shame, for which considerable credit must also be ascribed to chorus master, Jeremy Jackman.

Vocal soloists impressed too. If John Pierce’s recitatives sometimes passed uncomfortably into bluster, his arias were generally well phrased. David Pike’s rich tone did not preclude intelligent response to the words. I am not sure that anyone can redeem the dull ‘B’ section of ‘The trumpet shall sound’, but the principal material was especially pleasing, not least thanks to Paul Archibald’s excellent trumpet solo. Hannah Davey’s diction and phrasing often made one consider anew arias one might have thought one knew all too well. Perhaps the most welcome discovery of all was counter-tenor, Roderick Morris. Holding a prejudice here for a contralto, I was delighted to discover that I did not miss the female voice in the slightest. Morris’s voice brought a splendid sense of Baroque theatre to the occasion: despite his Oxford and Cambridge background, this was a supple, dramatic performance more in the mould of David Daniels than Alfred Deller (not that there is anything wrong with the latter). Ornamentation was tasteful and meaningful, less restrained than once would have been heard, but lending new life to Handel’s da capo arias, which can otherwise sometimes become a bit of a trial. There is plenty of life in Messiah yet.

For the greatest panache, utterly irresistible, save to those Beecham dubbed 'drowsy armchair purists':

For what remains to my mind the most recommendable 'straight' Messiah, full of life and supremely musical:

For Mozart's version:

An underrated digital account:

Hannah Davey (soprano)

Roderick Morris (counter-tenor)

John Pierce (tenor)

David Pike (baritone)

OSJ Voices (chorus master: Jeremy Jackman)

Orchestra of St John’s

John Lubbock (conductor)

This was a delight: very much a tonic to December blues. Time was when Hall One of Kings Place would have been considered risibly small for a performance of the Messiah – though time was when anywhere smaller than the Royal Albert Hall or even the Crystal Palace would have been. Monster Victorian performances from the likes of Sir Michael Costa are long gone, though we should do well to recall not only the popular enthusiasm they engendered but also their musical influence: Haydn, in London, heard a performance, which, if not Victorian, employed forces inconceivable today. It set him on the road to writing The Creation.

Back to Kings Place. This was a chamber performance, at least in terms of the orchestra, strings fewer than I have ever previously encountered: 3, 2, 2, 2, 1. That presents a few problems, not so much in terms of volume – even my knowledge of acoustics informs me that thirty first violins are not ten times as loud as three – but blend and tonal quality. (Indeed, one to a part, true chamber music, will lose the rough edges.) So there were occasions, especially when playing softly, when ensemble could prove a little rough. They should not, however, be exaggerated in importance, and should be balanced against considerable cultivation at other times. Vibrato was not eschewed, even if there were passages, more so in the First Part than later on, when more would have been welcome. Leader Richard Milone’s solo work was especially finely turned. And if there were occasions when John Lubbock indulged the contemporary fashion for abrupt endings to phrases – believe me, I have heard much, much worse – much of his characterisation of individual numbers proved both apt and refreshing. For instance, I do not recall hearing ‘He trusted in God that He would deliver Him’ performed with such anger, malice even: the great turba choruses of Bach’s St John Passion came to mind. Given that the words are those of the vicious mob, they who ‘laugh Him to scorn’, such a performance made excellent sense, imparting a greater narrative drive to a section of the oratorio that is not entirely without longueurs, whichever version is employed. (The present version did not, off the top of my head, correspond to any particular Handel performance, but worked well enough.)

Choral singing, from OSJ Voices, was excellent throughout. Forty-eight strong, according to the programme, this was by contemporary standards a fair-sized chorus, but it lacked little in agility, responding with alacrity to Lubbock’s keenness in numbers such as ‘And the glory of the Lord’. Weight was present where necessary too: indeed, the wholeheartedness to the closing choruses of the second and third parts was quite moving. (Almost everyone stood for the ‘Hallelujah’ Chorus. Two notable refuseniks were those who had chattered and disrupted with sweet-wrappers throughout. I shall remember their faces…) This, then, was a choral performance that would put many professional choirs to shame, for which considerable credit must also be ascribed to chorus master, Jeremy Jackman.

Vocal soloists impressed too. If John Pierce’s recitatives sometimes passed uncomfortably into bluster, his arias were generally well phrased. David Pike’s rich tone did not preclude intelligent response to the words. I am not sure that anyone can redeem the dull ‘B’ section of ‘The trumpet shall sound’, but the principal material was especially pleasing, not least thanks to Paul Archibald’s excellent trumpet solo. Hannah Davey’s diction and phrasing often made one consider anew arias one might have thought one knew all too well. Perhaps the most welcome discovery of all was counter-tenor, Roderick Morris. Holding a prejudice here for a contralto, I was delighted to discover that I did not miss the female voice in the slightest. Morris’s voice brought a splendid sense of Baroque theatre to the occasion: despite his Oxford and Cambridge background, this was a supple, dramatic performance more in the mould of David Daniels than Alfred Deller (not that there is anything wrong with the latter). Ornamentation was tasteful and meaningful, less restrained than once would have been heard, but lending new life to Handel’s da capo arias, which can otherwise sometimes become a bit of a trial. There is plenty of life in Messiah yet.

For the greatest panache, utterly irresistible, save to those Beecham dubbed 'drowsy armchair purists':

For what remains to my mind the most recommendable 'straight' Messiah, full of life and supremely musical:

For Mozart's version:

An underrated digital account:

Tuesday, 20 December 2011

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Royal Opera, 19 December 2011

|

| Pogner (Sir John Tomlinson) Images: Clive Barda/Royal Opera |

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Hans Sachs – Wolfgang Koch

Walther von Stolzing – Simon O’Neill

Eva – Emma Bell

Sixtus Beckmesser – Peter Coleman-Wright

Veit Pogner – Sir John Tomlinson

David – Toby Spence

Magdalene – Heather Shipp

Kunz Vogelsang – Colin Judson

Konrad Nachtigall – Nicholas Folwell

Fritz Kothner – Donald Maxwell

Hermann Ortel – Jihoon Kim

Balthazar Zorn – Martyn Hill

Augustin Moser – Pablo Bemsch

Ulrich Eisslinger – Andrew Rees

Hans Foltz – Jeremy WhiteHans Schwarz – Richard Wiegold

Nightwatchman – Robert Lloyd

Graham Vick (director)

Elaine Kidd (revival director)

Richard Hudson (designs)

Wolfgang Göbbel (lighting)

Ron Howell (movement)

Royal Opera Chorus (chorus master: Renato Balsadonna)

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

Antonio Pappano (conductor)

Hans Sachs would be the first to counsel us of the dangers of extolling past achievements at the expense of the present. It is an apt warning in the case of Wagner, for whom great performances, whether recorded or in the theatre, sear themselves with into the memory with perhaps unusual tenacity, acting as Mastersinger-guardians of the imagination. That said, whilst we should all beware the tendency to act as Beckmesser or worse, not every newcomer proves to be a Stolzing. At a time of year when some midsummer warmth, even magic, could hardly be more welcome, glad tidings were, sadly, thin onstage or in the pit.

|

| Walther (Simon O'Neill), Eva (Emma Bell), congregation |

This Marker has fond memories of Graham Vick’s production. It was the first he saw in the theatre, in 2000 and again in 2002; it seemed so full of joy and good humour; above all, it provided a seemingly perfect backdrop for the unforgettable greatness of Bernard Haitink’s conducting. (Mark Wigglesworth was far from put to shame in 2002.) Now, alas, it looks tired: there are few cases of production styles failing to date; in this, as in so much else, Patrice Chéreau’s Ring offers a near-miraculous exception. The evocation of Nuremberg in Richard Hudson’s sets seems as much of its time as John Major’s ‘Back to Basics’ (not that David Cameron seems to have noticed). Where once one saw Breugel, now one registers the lack of darkness in a work every bit as Schopenhauerian as Tristan und Isolde. What once was joyous now seems evasive. The ‘amusing’ antics of the apprentices now merely irritate. Time has passed, yes, but a good part of the problem seems to be the revival direction. Perhaps matters would have been different had Vick himself returned, but there seems to be precious little to Elaine Kidd’s direction beyond having singers don their costumes and sing: it resembles a repertory production in a provincial house rather than a performance on one of the world’s great stages. Oddly, the chorus often seems better directed than the singers. As for the codpieces, it would be an act of charity for all concerned to consign them to the dustbin of history.

|

| Beckmesser (Peter Coleman-Wright) attempting to sing the Prize Song |

|

| Apprentices, David (Toby Spence), Walther |

Sunday, 18 December 2011

Performances of the Year, 2011

If fate be tempted by the presentation of such a reckoning prior to the year's end, all the better: I should be delighted, verging upon astonished, if another performance this year came close to those below. The past couple of years, I have presented a list of twelve: an arbitrary number, of course, but akin to one per month, which did not seem unreasonable. This year, I have decided, in doubtless equally arbitrary fashion, to present four performances in each of six categories: instrumental, chamber, orchestral, vocal/choral, opera, and contemporary. The categories seemed a reasonable reflection of my listening: I am certainly not claiming that one could not come up with others, but it would be rather silly for me to have, say, a 'period performance' or an 'operatic recitals' category - though who knows what 2012 may bring? Part of the reason for this experiment was to give opera more of a chance, since almost any operatic performance is likely, given the large number of variables, to have something that might persuade one to eliminate it from consideration. It is not easy in any sense, of course, to give an outstanding performance of chamber music, but it almost seems so by comparison. I was in two minds concerning 'contemporary', since I do not wish to ghettoise new music from any other. However, on balance, I thought it a good way of drawing attention to excellent performances of excellent music that is truly of our time. (Not that Beethoven is not of our time, but that is another matter...) In the hope that such a preamble has not dissuaded readers from venturing further, here are my choices:

Instrumental

Performance of the Year

This is doubtless grossly, even obscenely, unfair to any other instrumentalist this year, since what could possible compare with the Southbank Centre's 'Pollini Project'? Five recitals, opening with the first book of Bach's Forty-Eight Preludes and Fugues, and culminating in Boulez's Second Piano Sonata. It might be thought cheating to select a whole series, rather than a single concert; if so, so much the better for cheating. Any one of Pollini's recitals could and would have made this list - save for the unfortunate matter of having chosen four performances per category - but the whole was even more than the sum of the parts, and those parts include an astounding account of the three final Beethoven sonatas.

Other contenders

Konstantin Lifschitz's Art of Fugue led one from Bergian chromaticism to Birtwistle's labyrinth, or rather Bach did. This, I wrote at the time, 'was music both for and beyond the piano, shimmering Romanticism and old-fashioned organ-reed registration dissolving or sublating themselves seamlessly into abstraction that yet reached beyond abstraction.' I also wrote that I should be astonished if it did not prove to be one of my performances of the year: no need for further astonishment.

Pollini again, I am afraid: this time in Salzburg, with four more Beethoven sonatas, nos 21-24. The tragic inevitability of the Appassionata and the coruscating chiaroscuro of the Waldstein simply had to be heard to be believed, but equally estimable was the emergence of the scandalously-overlooked F-sharp major sonata as Romantic character-piece.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard's two-concert 'Liszt Project' - might we perhaps rid ourselves of the modish 'project' next year? - placed a little of the still grossly misunderstood composer's finest piano music in the context of followers from Wagner to Marco Stroppa. Context may mean a great deal, but not all, for Aimard's B minor sonata could hold its own in any company whatsoever.

Chamber

Performance of the Year

The Quatuor Ebène's visits to the Wigmore Hall are eagerly awaited; I have yet to be disappointed. Prokofiev, Debussy, and Brahms all received exquisite, profoundly musical treatment from this fine group of musicians. Unanimity of ensemble never sounded slick; it simply arose out of the excellence of their playing - and listening. Prokofiev's first quartet emerged as far more than a concatenation of melodies; Debussy's quartet formed a perfect cyclical whole; Brahms's second essay in the genre glowed, captivated, and profoundly satisfied.

Other Contenders

Sir Simon Rattle's Berlin Philharmonic account of Mahler's Third Symphony was roaringly acclaimed, though in truth it was a dreadfully mannered affair. The opening concert of the BPO's four-night London residency was an immeasurably superior experience, offering the musicians in chamber mode for works by Schubert, Mahler, and Schoenberg. The Schoenberg performances will perhaps linger longest in the memory. For the Second String Quartet, Anna Prohaska joined the ensemble, violence and melodic profusion proving two sides of the Schoenbergian coin. Rattle directed his players in the First Chamber Symphony, an exhilirating ride with none of the infuriating mannerisms of his Mahler, whose early piano quartet can rarely have received such persuasive advocacy.

Schoenberg again, for the Jerusalem Quartet and friends. Verklärte Nacht was performed as true chamber music, not an aspirant orchestral work, though with no loss to its glittering 'pictorial' elements, quite the contrary. Climaxes sent shivers down the spince. Brahms's string sextet offered ghosts from the Classical past, battling and yet affirming them.

It sounds like madness, and it probably is, to perform Schubert's C major String Quintet in the Royal Albert Hall. Yet somehow, the Belcea Quartet and Valentin Erben managed to draw one in. Ambivalence and regret were certainly present; so was quiet determination. Heavenly lengths seemed all too short, all too mortal.

Orchestral

Performance of the Year

The Staatskapelle Berlin and Pierre Boulez provided, along with Aimard's 'project' (see above), the highlight of this year's Liszt anniversary. Despite an erratic performance of the second piano concerto from Daniel Barenboim, the first concerto emerged very much in the line of Beethoven: a musicianly riposte to any idea of Liszt as mere showman. Finer still, though, were Boulez's Wagner performances, both revelatory: a questing Faust Overture and a truly magical, properly symphonic Siegfried-Idyll, outstripping any I have ever heard, live or on record. For that alone, this concert would surely deserve top billing. If only the Wagner pieces had been recorded along with the concertos by Deutsche Grammophon .

Other contenders

Bernard Haitink's Ravel and Mendelssohn with the LSO presented the Mother Goose Suite with an unforced nobility that hinted at Elgar, with no cost to orchestral bite. Solos were as excellent as one would expect from this orchestra. The Midsummer Night's Dream music offered almost Wagnerian musico-dramatic flow through which gossamer delight was spun.

The hype surrounding a visit to London from Claudio Abbado and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra - would The Guardian kindly calm down, at least until after a few notes have been played? - inclines one to react adversely, but these performances were outstanding. Abbado's latter-day way with Mozart has won ecstatic plaudits, though I have remained sceptical; not so here, for this was a Haffner Symphony of surpassing elegance. Bruckner's Fifth Symphony remains something of an enigma to me, but Abbado's reading probed, without offering easy answers. What a collection of musicians, moreover, is to be heard in this orchestra!

Throughout the year, the Philharmonia and Esa-Pekka Salonen have been celebrating Bartók, in a series named 'Infernal Dance'. An October concert brought Contrasts, the Wooden Prince suite, the Dance Suite, and the second piano concerto (Yefim Bronfman). An utterly gorgeous account of the Wooden Prince suite left one longing for the entire ballet, rhythmic exactitude and sheer fantasy united.

Vocal/Choral

Performance of the Year

No question whatsoever here: Sir Colin Davis's Proms performance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis. If you think no one has come close to Klemperer, listen to Davis. With the LSO and London Symphony Chorus on superlative form, we were taken to the abyss, and never quite drew back. Perfection is not a word this work recognises, but greatness and impossibility both are; the same goes for this performance. LSO Live only issues recordings from the Barbican, but might it make an exception, or might someone else issue a recording? It is not only desirable but absolutely necessary to do so.

Other Contenders

The same orchestra and chorus offered a scintillating performance, this time under the baton of Sir Mark Elder, of Elgar's resolutely unfashionable oratorio, The Kingdom. Urgency, dramatic tension, and again, that trademark Elgar word, 'nobility, were there in abundance. I doubt that the work has ever received more glorious choral singing than it did from the LSC.

Bach's St John Passion suffers none of the difficulties concerning taste that The Kingdom does, though I am not sure why that ought to be the case. Many of those who sing its praises would surely be distressed by its message, were they to heed it. For the rest of us, it remains, of course, a towering masterpiece, though present-day performances often fall horrendously short of registering its shattering impact. This Good Friday performance from the Thomaskirche came closer than many, in part because its unassuming quality simply permitted the extraordinary narrative to emerge for itself. Johannes Chum was an excellent Evangelist, Stephan Loges a richly toned, dignified Christ.

Another masterpiece only a madman would deny, though perhaps it renders one more than a little mad to experience it, is Schubert's Winterreise. Movingly, indeed terrifyingly, performed by Pierre-Laurent Aimard (again, I know) and Simon Keenlyside, Schubert in Salzburg offered no Mozartkugeln consolations: instead we looked forward to Wozzeck, even beyond. (Audience behaviour, alas, was nothing short of unforgivable.)

Opera

Performance of the Year

Monteverdi brought musical drama to a level that has been surpassed, perhaps, only by Mozart and Wagner, and equalled by very few. The English National Opera's Return of Ulysses, was, quite simply, essential theatre. Benedict Andrews's production at the Young Vic grabbed one from the outset, the Prologue's Abu Ghraib-style abuse of Human Frailty gloatingly captured on camera, and never let one go. Minerva emerged more a trickster than Ulysses? Was she even a goddess at all? Jonathan Cohen led members of the ENO orchestra with great dramatic flair, Pamela Helen Stephen and Tom Randle heading an outstanding cast.

Other Contenders

Christoph Marthaler's Katya Kabanova received its final outing in Paris, at the Palais Garnier. Thank goodness I caught up with it in time. A drab apartment block and its closed moral world provided the setting for searing musical drama, courtesy of Angela Denoke, Jane Henschel, et al. Katya's goodness shone through with almost unbearably moving effect; the Kabanicha horrified as only she can.

Back to the Coliseum, for ENO's brilliant Midsummer Night's Dream. Leo Hussain, making his ENO debut, conducted a magical account of the score, that magic questioned and deepened at every turn by Christopher Alden's tremendous production. Anathema to loyalists to an Aldeburgh that never was, this was a world of twisted abuse, tormented memory, and troubled defiance. The school entrance said it all, in brazen capital letters: 'BOYS'.

Stefan Herheim's Bayreuth production of Parsifal is, not to beat about the bush, one of the great Wagner stagings of all time. It remains electrifying; it remains faithful; it remains questioning; it remains far more than anyone could possibly take in on a single viewing, which is why I felt properly blessed to be granted a second helping. The tightrope remains precarious: can he really simultaneously tell the story of Parsifal both in Wagner's terms and those of its reception? Yes he can. Daniele Gatti's masterly pacing upset some impatient souls, but the score unfolded as if in a single breath: the only true measure of Wagner performance. If only the roles of Gurnemanz and Parsifal himself had been better filled, this would have been my opera, and not just my Bühnenweihfestspiel, of the year.

Contemporary

Performance of the Year

As with the 'Pollini Project', the Southbank Centre did not permit anything else a chance with its unforgettable weekend, 'Exquisite Labyrinth: the Music of Pierre Boulez'. Pierre-Laurent Aimard - what a year for him! - and Tamara Stepanovich offered the almost-complete piano works, replete with second-to-none analytical commentary from Aimard. The London Sinfonietta provided the mesmerising moment when I fell head over heals in love with ...explosante-fixe. Above all, Barbara Hannigan, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, and Boulez himself put one in no doubt whatsoever that Pli selon pli is not just a modern masterpiece, but a masterpiece tout court. This was as seductive as Mozart.

Other Contenders

The Arditti Quartet performed four contemporary quartets, two world premieres, two mere London premieres. James Clarke's second quartet proved an intense musico-dramatic experience, Bryan Ferneyhough's sixth less fragmentary, more melodic, than one might have expected, though certainly no less challenging. Hilda Parades’s Canciones lunáticas, with Jake Arditti as counter-tenor soloist, delightfully enjoined us to dance with the moon.

Bruno Mantovani's Akhmatova received its world premiere at the Bastille earlier this year. From the opening viola solo, there was no doubt that musical considerations were to the fore of this new opera. (What a contrast with Anna Nicole, which I had heard just the month before, in London!) Akhmatova is almost a concerto for orchestra, with voices. Yet not quite; for, even if Christophe Ghristi's libretto is far from avant-garde, a burning question remains with one, the question that is Anna Akhmatova's own: should a poetess have children?

There is certainly a French theme in this contemporary selection, my final choice being an outstanding performance from the Neuevocalsolisten Stuttgart and the Ensemble Intercontemporain of works by Mantovani, Ivan Fedele, and Johannes Maria Staud. Fedele's Animus anima II exulted and beguiled; Staud's Par ici! emerged almost as a Lisztian tone-poem for the twenty-first-century; Mantovani's Cantata no.1 proved fully worthy of Rilke's verse, Bach refracted through the ages.

Instrumental

Performance of the Year

This is doubtless grossly, even obscenely, unfair to any other instrumentalist this year, since what could possible compare with the Southbank Centre's 'Pollini Project'? Five recitals, opening with the first book of Bach's Forty-Eight Preludes and Fugues, and culminating in Boulez's Second Piano Sonata. It might be thought cheating to select a whole series, rather than a single concert; if so, so much the better for cheating. Any one of Pollini's recitals could and would have made this list - save for the unfortunate matter of having chosen four performances per category - but the whole was even more than the sum of the parts, and those parts include an astounding account of the three final Beethoven sonatas.

Other contenders

Konstantin Lifschitz's Art of Fugue led one from Bergian chromaticism to Birtwistle's labyrinth, or rather Bach did. This, I wrote at the time, 'was music both for and beyond the piano, shimmering Romanticism and old-fashioned organ-reed registration dissolving or sublating themselves seamlessly into abstraction that yet reached beyond abstraction.' I also wrote that I should be astonished if it did not prove to be one of my performances of the year: no need for further astonishment.

Pollini again, I am afraid: this time in Salzburg, with four more Beethoven sonatas, nos 21-24. The tragic inevitability of the Appassionata and the coruscating chiaroscuro of the Waldstein simply had to be heard to be believed, but equally estimable was the emergence of the scandalously-overlooked F-sharp major sonata as Romantic character-piece.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard's two-concert 'Liszt Project' - might we perhaps rid ourselves of the modish 'project' next year? - placed a little of the still grossly misunderstood composer's finest piano music in the context of followers from Wagner to Marco Stroppa. Context may mean a great deal, but not all, for Aimard's B minor sonata could hold its own in any company whatsoever.

Chamber

Performance of the Year

The Quatuor Ebène's visits to the Wigmore Hall are eagerly awaited; I have yet to be disappointed. Prokofiev, Debussy, and Brahms all received exquisite, profoundly musical treatment from this fine group of musicians. Unanimity of ensemble never sounded slick; it simply arose out of the excellence of their playing - and listening. Prokofiev's first quartet emerged as far more than a concatenation of melodies; Debussy's quartet formed a perfect cyclical whole; Brahms's second essay in the genre glowed, captivated, and profoundly satisfied.

Other Contenders

Sir Simon Rattle's Berlin Philharmonic account of Mahler's Third Symphony was roaringly acclaimed, though in truth it was a dreadfully mannered affair. The opening concert of the BPO's four-night London residency was an immeasurably superior experience, offering the musicians in chamber mode for works by Schubert, Mahler, and Schoenberg. The Schoenberg performances will perhaps linger longest in the memory. For the Second String Quartet, Anna Prohaska joined the ensemble, violence and melodic profusion proving two sides of the Schoenbergian coin. Rattle directed his players in the First Chamber Symphony, an exhilirating ride with none of the infuriating mannerisms of his Mahler, whose early piano quartet can rarely have received such persuasive advocacy.

Schoenberg again, for the Jerusalem Quartet and friends. Verklärte Nacht was performed as true chamber music, not an aspirant orchestral work, though with no loss to its glittering 'pictorial' elements, quite the contrary. Climaxes sent shivers down the spince. Brahms's string sextet offered ghosts from the Classical past, battling and yet affirming them.

It sounds like madness, and it probably is, to perform Schubert's C major String Quintet in the Royal Albert Hall. Yet somehow, the Belcea Quartet and Valentin Erben managed to draw one in. Ambivalence and regret were certainly present; so was quiet determination. Heavenly lengths seemed all too short, all too mortal.

Orchestral

Performance of the Year

The Staatskapelle Berlin and Pierre Boulez provided, along with Aimard's 'project' (see above), the highlight of this year's Liszt anniversary. Despite an erratic performance of the second piano concerto from Daniel Barenboim, the first concerto emerged very much in the line of Beethoven: a musicianly riposte to any idea of Liszt as mere showman. Finer still, though, were Boulez's Wagner performances, both revelatory: a questing Faust Overture and a truly magical, properly symphonic Siegfried-Idyll, outstripping any I have ever heard, live or on record. For that alone, this concert would surely deserve top billing. If only the Wagner pieces had been recorded along with the concertos by Deutsche Grammophon .

Other contenders

Bernard Haitink's Ravel and Mendelssohn with the LSO presented the Mother Goose Suite with an unforced nobility that hinted at Elgar, with no cost to orchestral bite. Solos were as excellent as one would expect from this orchestra. The Midsummer Night's Dream music offered almost Wagnerian musico-dramatic flow through which gossamer delight was spun.

The hype surrounding a visit to London from Claudio Abbado and the Lucerne Festival Orchestra - would The Guardian kindly calm down, at least until after a few notes have been played? - inclines one to react adversely, but these performances were outstanding. Abbado's latter-day way with Mozart has won ecstatic plaudits, though I have remained sceptical; not so here, for this was a Haffner Symphony of surpassing elegance. Bruckner's Fifth Symphony remains something of an enigma to me, but Abbado's reading probed, without offering easy answers. What a collection of musicians, moreover, is to be heard in this orchestra!

Throughout the year, the Philharmonia and Esa-Pekka Salonen have been celebrating Bartók, in a series named 'Infernal Dance'. An October concert brought Contrasts, the Wooden Prince suite, the Dance Suite, and the second piano concerto (Yefim Bronfman). An utterly gorgeous account of the Wooden Prince suite left one longing for the entire ballet, rhythmic exactitude and sheer fantasy united.

Vocal/Choral

Performance of the Year

No question whatsoever here: Sir Colin Davis's Proms performance of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis. If you think no one has come close to Klemperer, listen to Davis. With the LSO and London Symphony Chorus on superlative form, we were taken to the abyss, and never quite drew back. Perfection is not a word this work recognises, but greatness and impossibility both are; the same goes for this performance. LSO Live only issues recordings from the Barbican, but might it make an exception, or might someone else issue a recording? It is not only desirable but absolutely necessary to do so.

Other Contenders

The same orchestra and chorus offered a scintillating performance, this time under the baton of Sir Mark Elder, of Elgar's resolutely unfashionable oratorio, The Kingdom. Urgency, dramatic tension, and again, that trademark Elgar word, 'nobility, were there in abundance. I doubt that the work has ever received more glorious choral singing than it did from the LSC.

Bach's St John Passion suffers none of the difficulties concerning taste that The Kingdom does, though I am not sure why that ought to be the case. Many of those who sing its praises would surely be distressed by its message, were they to heed it. For the rest of us, it remains, of course, a towering masterpiece, though present-day performances often fall horrendously short of registering its shattering impact. This Good Friday performance from the Thomaskirche came closer than many, in part because its unassuming quality simply permitted the extraordinary narrative to emerge for itself. Johannes Chum was an excellent Evangelist, Stephan Loges a richly toned, dignified Christ.

Another masterpiece only a madman would deny, though perhaps it renders one more than a little mad to experience it, is Schubert's Winterreise. Movingly, indeed terrifyingly, performed by Pierre-Laurent Aimard (again, I know) and Simon Keenlyside, Schubert in Salzburg offered no Mozartkugeln consolations: instead we looked forward to Wozzeck, even beyond. (Audience behaviour, alas, was nothing short of unforgivable.)

Opera

Performance of the Year

Monteverdi brought musical drama to a level that has been surpassed, perhaps, only by Mozart and Wagner, and equalled by very few. The English National Opera's Return of Ulysses, was, quite simply, essential theatre. Benedict Andrews's production at the Young Vic grabbed one from the outset, the Prologue's Abu Ghraib-style abuse of Human Frailty gloatingly captured on camera, and never let one go. Minerva emerged more a trickster than Ulysses? Was she even a goddess at all? Jonathan Cohen led members of the ENO orchestra with great dramatic flair, Pamela Helen Stephen and Tom Randle heading an outstanding cast.

Other Contenders

Christoph Marthaler's Katya Kabanova received its final outing in Paris, at the Palais Garnier. Thank goodness I caught up with it in time. A drab apartment block and its closed moral world provided the setting for searing musical drama, courtesy of Angela Denoke, Jane Henschel, et al. Katya's goodness shone through with almost unbearably moving effect; the Kabanicha horrified as only she can.

Back to the Coliseum, for ENO's brilliant Midsummer Night's Dream. Leo Hussain, making his ENO debut, conducted a magical account of the score, that magic questioned and deepened at every turn by Christopher Alden's tremendous production. Anathema to loyalists to an Aldeburgh that never was, this was a world of twisted abuse, tormented memory, and troubled defiance. The school entrance said it all, in brazen capital letters: 'BOYS'.

Stefan Herheim's Bayreuth production of Parsifal is, not to beat about the bush, one of the great Wagner stagings of all time. It remains electrifying; it remains faithful; it remains questioning; it remains far more than anyone could possibly take in on a single viewing, which is why I felt properly blessed to be granted a second helping. The tightrope remains precarious: can he really simultaneously tell the story of Parsifal both in Wagner's terms and those of its reception? Yes he can. Daniele Gatti's masterly pacing upset some impatient souls, but the score unfolded as if in a single breath: the only true measure of Wagner performance. If only the roles of Gurnemanz and Parsifal himself had been better filled, this would have been my opera, and not just my Bühnenweihfestspiel, of the year.

Contemporary

Performance of the Year

As with the 'Pollini Project', the Southbank Centre did not permit anything else a chance with its unforgettable weekend, 'Exquisite Labyrinth: the Music of Pierre Boulez'. Pierre-Laurent Aimard - what a year for him! - and Tamara Stepanovich offered the almost-complete piano works, replete with second-to-none analytical commentary from Aimard. The London Sinfonietta provided the mesmerising moment when I fell head over heals in love with ...explosante-fixe. Above all, Barbara Hannigan, the Ensemble Intercontemporain, and Boulez himself put one in no doubt whatsoever that Pli selon pli is not just a modern masterpiece, but a masterpiece tout court. This was as seductive as Mozart.

Other Contenders

The Arditti Quartet performed four contemporary quartets, two world premieres, two mere London premieres. James Clarke's second quartet proved an intense musico-dramatic experience, Bryan Ferneyhough's sixth less fragmentary, more melodic, than one might have expected, though certainly no less challenging. Hilda Parades’s Canciones lunáticas, with Jake Arditti as counter-tenor soloist, delightfully enjoined us to dance with the moon.

Bruno Mantovani's Akhmatova received its world premiere at the Bastille earlier this year. From the opening viola solo, there was no doubt that musical considerations were to the fore of this new opera. (What a contrast with Anna Nicole, which I had heard just the month before, in London!) Akhmatova is almost a concerto for orchestra, with voices. Yet not quite; for, even if Christophe Ghristi's libretto is far from avant-garde, a burning question remains with one, the question that is Anna Akhmatova's own: should a poetess have children?

There is certainly a French theme in this contemporary selection, my final choice being an outstanding performance from the Neuevocalsolisten Stuttgart and the Ensemble Intercontemporain of works by Mantovani, Ivan Fedele, and Johannes Maria Staud. Fedele's Animus anima II exulted and beguiled; Staud's Par ici! emerged almost as a Lisztian tone-poem for the twenty-first-century; Mantovani's Cantata no.1 proved fully worthy of Rilke's verse, Bach refracted through the ages.

Saturday, 17 December 2011

Chapelle du Roi/Dixon: Byrd, Fayrfax, Sheppard, Tallis, and Victoria, 17 December 2011

St John’s, Smith Square

Sarum chant: A solis ortus cardine

Byrd – Rorate cœli

Fayrfax – Magnificat, ‘Regale’

Sheppard: Verbum caro

Tallis – Beati Immaculati

Tallis – Suscipe quæso Domine

Tallis – If ye love me

Sheppard – I give you a new commandment

Byrd – Hodie Christus natus est

Tallis – Videte miraculum

Tallis – Te Deum

Victoria – Alma Redemptoris Mater

Chapelle du Roi

Alistair Dixon (director)

The ‘Christmas Festival’ at St John’s, Smith Square is now well under way, despite there being a week to go of Advent, a peculiarity of nomenclature rendered all the more peculiar given that sacred music provides the staple diet. But the name chosen for the present concert was also a little odd: ‘Meet the Tudors’. There was nothing especially regal about the works performed, no more or no less than one might expect from a programme of late-fifteenth-, sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century English sacred music. Byrd’s Gradualia, from which both the motets performed here are taken, was published two years after the death of Elizabeth I. Victoria’s presence, whilst welcome, also seemed odd, given the vague ‘concept’: a nod to Philip II perhaps? Chapelle du Roi, or rather its director, Alistair Dixon, would have been better advised either to let the music speak for itself, or to provide more of a guiding thematic link.

For the music is perfectly capable of speaking for itself, especially in capable performances such as these generally proved to be. The opening, processional Sarum hymn provided more ‘historical’ perspective than much of the rest of the programme, reminding us of the richness of English mediæval tradition, liturgical and musical, much of it wantonly destroyed by the Reformers’ zeal. Byrd’s introit, Rorate cœeli, flowed yet yielded, the eight voices of Chapelle du Roi, showing the advantages of a small choir even to those of us who might be inclined to hanker after the likes of King’s College, Cambridge, in such repertoire. Robert Fayrfax’s Magnificat was the sole representative of the Eton Choirbook. It unfolded as ‘naturally’ as one had any right to expect, a fine centrepiece to the first half. Not for the last time, however, there was a degree of dryness to the lower voices, the tenors especially, and there were a few intonational difficulties. More seriously, the ‘Esurientes’ section had to be restarted following a serious lapse of ensemble, though Dixon carried that difficult task off with a minimum of fuss.

John Sheppard’s Christmas Day Verbum caro suffered from occasional shortness of breath, leading phrases to fall away a little more than they should, though there were some properly plangent contributions to enjoy from the two counter-tenors. It was a pity, then, that they lapsed somewhat into hooting at the opening of Tallis’s Beati Immaculati. That, otherwise, was an interesting as well as musically satisfying performance, given that it was presented in a Latin version, on the supposition that the composer’s Blessed are those that be undefiled was itself a contrafactum version of a Latin original. Tallis’s Suscipe quæso Domine received a disarmingly heartfelt, expressive reading, its unusual qualities – not least the seven-part texture – observed and communicated, without undue exaggeration.

Tallis returned after the interval. If ye love me – most collegiate choirs love this anthem very much – was sung by four solo men’s voices, likewise Sheppard’s I give you a new commandment, albeit four different voices: now two tenors and two basses. (Neither piece was conducted.) Byrd’s Hodie Christus natus est was beset by a degree of fuzziness from the tenors, though it received a lively, if perhaps unduly hard-driven, performance. Videte miraculum, by Tallis, formed the counterpart to Fayrfax’s work in the first half. Written for the First Vespers of Candlemas, its Marian dissonances – it being impressed upon us how Mary is laden with a noble burden, ‘Stans onerata nobili onere Maria’ – were expressively handled and projected. ‘Knowing that she is not a wife, she rejoices to be a mother’ (‘Et matrem se lætam cognosci, quæ se nescit uxorem’), the two sopranos in particular emphasising the imploring nature of Tallis’s word-setting here.

We remained with Tallis for his English Te Deum. The initial cantorial intonation was not blessed with the strongest intonation in another sense. There was, moreover, something oddly chamber-like to the performance, the only occasion when I truly missed the forces of a larger choir. Somehow, the style seemed more appropriate to a recusant Byrd motet than to the grandeur of words and music. Nevertheless, antiphonal placing of the singers – essentially, one-to-a-part double choir – offered compensatory keenness of response, almost madrigalian in relatively-restrained English fashion. No ‘Gloria’ was given. Victoria’s Alma Redemptoris Mater sounded as if from another world, the warmth of its opening immediately felt: this was clearly music from Mediterranean, albeit Counter-Reformatory, climes.

Sarum chant: A solis ortus cardine

Byrd – Rorate cœli

Fayrfax – Magnificat, ‘Regale’

Sheppard: Verbum caro

Tallis – Beati Immaculati

Tallis – Suscipe quæso Domine

Tallis – If ye love me

Sheppard – I give you a new commandment

Byrd – Hodie Christus natus est

Tallis – Videte miraculum

Tallis – Te Deum

Victoria – Alma Redemptoris Mater

Chapelle du Roi

Alistair Dixon (director)

The ‘Christmas Festival’ at St John’s, Smith Square is now well under way, despite there being a week to go of Advent, a peculiarity of nomenclature rendered all the more peculiar given that sacred music provides the staple diet. But the name chosen for the present concert was also a little odd: ‘Meet the Tudors’. There was nothing especially regal about the works performed, no more or no less than one might expect from a programme of late-fifteenth-, sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century English sacred music. Byrd’s Gradualia, from which both the motets performed here are taken, was published two years after the death of Elizabeth I. Victoria’s presence, whilst welcome, also seemed odd, given the vague ‘concept’: a nod to Philip II perhaps? Chapelle du Roi, or rather its director, Alistair Dixon, would have been better advised either to let the music speak for itself, or to provide more of a guiding thematic link.

For the music is perfectly capable of speaking for itself, especially in capable performances such as these generally proved to be. The opening, processional Sarum hymn provided more ‘historical’ perspective than much of the rest of the programme, reminding us of the richness of English mediæval tradition, liturgical and musical, much of it wantonly destroyed by the Reformers’ zeal. Byrd’s introit, Rorate cœeli, flowed yet yielded, the eight voices of Chapelle du Roi, showing the advantages of a small choir even to those of us who might be inclined to hanker after the likes of King’s College, Cambridge, in such repertoire. Robert Fayrfax’s Magnificat was the sole representative of the Eton Choirbook. It unfolded as ‘naturally’ as one had any right to expect, a fine centrepiece to the first half. Not for the last time, however, there was a degree of dryness to the lower voices, the tenors especially, and there were a few intonational difficulties. More seriously, the ‘Esurientes’ section had to be restarted following a serious lapse of ensemble, though Dixon carried that difficult task off with a minimum of fuss.

John Sheppard’s Christmas Day Verbum caro suffered from occasional shortness of breath, leading phrases to fall away a little more than they should, though there were some properly plangent contributions to enjoy from the two counter-tenors. It was a pity, then, that they lapsed somewhat into hooting at the opening of Tallis’s Beati Immaculati. That, otherwise, was an interesting as well as musically satisfying performance, given that it was presented in a Latin version, on the supposition that the composer’s Blessed are those that be undefiled was itself a contrafactum version of a Latin original. Tallis’s Suscipe quæso Domine received a disarmingly heartfelt, expressive reading, its unusual qualities – not least the seven-part texture – observed and communicated, without undue exaggeration.

Tallis returned after the interval. If ye love me – most collegiate choirs love this anthem very much – was sung by four solo men’s voices, likewise Sheppard’s I give you a new commandment, albeit four different voices: now two tenors and two basses. (Neither piece was conducted.) Byrd’s Hodie Christus natus est was beset by a degree of fuzziness from the tenors, though it received a lively, if perhaps unduly hard-driven, performance. Videte miraculum, by Tallis, formed the counterpart to Fayrfax’s work in the first half. Written for the First Vespers of Candlemas, its Marian dissonances – it being impressed upon us how Mary is laden with a noble burden, ‘Stans onerata nobili onere Maria’ – were expressively handled and projected. ‘Knowing that she is not a wife, she rejoices to be a mother’ (‘Et matrem se lætam cognosci, quæ se nescit uxorem’), the two sopranos in particular emphasising the imploring nature of Tallis’s word-setting here.

We remained with Tallis for his English Te Deum. The initial cantorial intonation was not blessed with the strongest intonation in another sense. There was, moreover, something oddly chamber-like to the performance, the only occasion when I truly missed the forces of a larger choir. Somehow, the style seemed more appropriate to a recusant Byrd motet than to the grandeur of words and music. Nevertheless, antiphonal placing of the singers – essentially, one-to-a-part double choir – offered compensatory keenness of response, almost madrigalian in relatively-restrained English fashion. No ‘Gloria’ was given. Victoria’s Alma Redemptoris Mater sounded as if from another world, the warmth of its opening immediately felt: this was clearly music from Mediterranean, albeit Counter-Reformatory, climes.

Thursday, 15 December 2011

When Valery Abisalovich called Vladimir Vladimirovich...

According to The Guardian, Valery Gergiev has called the Russian Prime Minister on his annual 'phone-in'. Luke Harding reports:

Valery Gergiev, lest anyone need reminding, is Principal Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra. It is difficult to conceive of his predecessor, Sir Colin Davis, having behaved similarly. Imagine Sir Colin, when Music Director of the Royal Opera, calling Margaret Thatcher and likening her to Gloriana...

Gergiev likens Putin to the composer Sergei Prokoviev "who came up with a lot of different productions". (Is this a way of saying Putin should go on and on?) Russia isn't just an oil and gas country but a country rich in poets and writers, Gergiev says. A classic piece of quality toadying, if you ask me.(I wonder what the original Russian for 'different productions' was; there is always the possibility, doubtless, that something might have been lost in translation.) Click here for a fuller report from The Guardian on the Russian people's audience with its present Tsar. For a time when Russian rulers - and just maybe, even top-ranking musicians - had a few more scruples, see below:

Putin is clearly delighted by the question. He says he loves St Petersberg [sic], where Gergiev is general and artistic director of the celebrated Mariinsky Theatre. Putin says he will do his best to support Russian culture.

Gergiev is now praising Putin, comparing him to Peter the Great, and Catherine the Great. Putin chides Gergiev for stealing artists for his theatre from Moscow's famous Bolshoi. This is all very pally.

Valery Gergiev, lest anyone need reminding, is Principal Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra. It is difficult to conceive of his predecessor, Sir Colin Davis, having behaved similarly. Imagine Sir Colin, when Music Director of the Royal Opera, calling Margaret Thatcher and likening her to Gloriana...

Tuesday, 13 December 2011

However violent our disagreements concerning movement order in Mahler's Sixth Symphony...

... we can all agree upon the necessity of an excellent cowbell player:

Monday, 12 December 2011

Quatuor Ebène: Prokofiev, Debussy, and Brahms, 12 December 2011

Wigmore Hall

Prokofiev – String Quartet no.1 in B minor, op.50

Debussy – String Quartet in G minor, op.10

Brahms – String Quartet in A minor, op.51 no.2

Pierre Colombet, Gabriel Le Magadure (violins),

Mathieu Herzog (viola)

Raphaël Merlin (violoncello)

The Quatuor Ebène’s visits to the Wigmore Hall have proved chamber music highlights of their respective seasons for some time now; the present concert did nothing to buck that trend. This was an evening of superlative quartet playing, even by the players’ own exalted standards, a welcome respite from but also challenge to the vile weather currently sweeping the streets of London.

First on was Prokofiev. There is some fine music to his two quartets, especially in this, his first, though it would be difficult to argue that he was the most natural of string quartet composers. Even the key, B minor, is somewhat perverse, as any cellist will tell you. Not that one would have guessed the problems from this performance, in which, the Ebène quite rightly acted as counsel for the defence. The first movement witnessed the identity of the themes and greater structure clearly and keenly delineated. Intriguingly, here and throughout, this was a more highly-strung – if the pun may be forgiven – Prokofiev who emerged than one often hears in his chamber music, partly a matter in this first movement of a fastish tempo but also, crucially, truly dramatic tension. There was excellent, productive contrast between the players acting as soloists and as part of an ensemble, voices emerging therefrom where called upon, and seamlessly blending back into the texture thereafter. Last but not least was a recognition that, in this music as in so much of the rest of his output, Prokofiev’s greatest gift was as a melodist. Then there came as powerful a contrast, without undue exaggeration, as one might wish for between the slow, vaguely Beethovenian introduction to the slow movement and the ‘Vivace’ proper, its thrills as visceral as they were musical. Rhythmic command and ensemble were outstanding, the quartet rightly playing Prokofiev with the abandon and the coherence one would expect in Bartók. This was Prokofiev the modernist with a vengeance, all the more striking since one expects to find him more readily elsewhere. The final ‘Andante’ permitted each player to present – ‘display’ would give entirely the wrong impression – his particular quality to the turning of a melodic phrase, and equally his own individuality of tone. In the broadest of generalisations, one therefore heard the suavity of cellist Raphaël Merlin, the richness of Mathieu Herzog’s viola, the burning intensity of Gabriel Le Magadure on second violin, and a sweet-toned, Cinderella-like lyricism, tinged with Grumiaux-like elegance from Pierre Colombet’s first violin. At least that was the impression at one point, for the changing demands of the music at its more hysterical would at least partially transform those qualities, to highly dramatic effect. Yet above all, this movement was lyrical, in a fashion out of which its form could emerge as naturally as I have yet to hear.

Debussy’s quartet completed the first half. Its first movement opened in a different yet recognisable manner: suavely graceful, the tone more obviously Gallic, though that certainly did not preclude intensity at climaxes. Indeed this could, where appropriate, be Debussy as impassioned as one might hope for – though never more so. Cyclic concision was a hallmark of the entire reading, not least in the transmission of the crucial triplet figure from the first to the second movement, and also of course beyond. That second movement burned with concentrated intensity, albeit with plenty of opportunity, never overlooked, for refreshment in contrast. Unanimity of ensemble never sounded clinical or slick – one can think of a few well-known quartets for whom that would not have been the case – but arose out of straightforwardly excellent, ever-alert quartet-playing. The ‘Andantino’ was given an elegant, sweetly melodic reading, exhibiting a degree of repose, though only relatively so, for it was no less attentive than any other movement to the relationship between detail and the whole. An urgent but satisfying cyclic unification marked the finale, movement and work becoming much more than the sum of their parts. Everything fell into place, though not bureaucratically; it was more a matter of ultimate victory for an Apollonian imperative.

Brahms’s second quartet was heard after the interval. Again, the sonority one heard could be characterised as different and yet the same. (I thought of Hans Sachs advising Walther that a song cannot always be for spring.) The general sound was more deeply Germanic, as one would expect, yet remained blessed by the elegance and clarity the best Franco-Flemish players have often brought to this repertoire. There was more than a hint of Schubert’s ‘Rosamunde’ Quartet, perhaps especially to the first movement’s second subject, though the motivic working unsurprisingly emerged more tightly-knit. Throughout, the players showed themselves heedful of Brahms’s melodic impulse, which engenders its own passions; there is no need to apply anything from without. Again, the Classical and Romantic were held in well-judged balance and tension during the second movement: not in some abstract equilibrium, but according to the particular needs of the material. The relative minor’s intervention was impassioned and not without influential, but the intermezzo-like mood ultimately if uneasily prevailed. Brahms’s Beethovenian inheritance was readily felt in the alternating, conflicting material of the third movement, vividly dramatised. There was even a hint of Haydn in the faster scherzo music, though Schubert again proved the principal ghost in its more wistful counterpart. The finale made clear that, as ever with Brahms, any ‘Hungarian’ colouring is just that: colouring. The real battle to be fought is ‘German’, through and through, its contrapuntal travails here evoking Beethoven and Bach, whilst inevitably looking forward also to Schoenberg. There was charm too, of an undeniably Viennese variety, though tragedy would out.

Prokofiev – String Quartet no.1 in B minor, op.50

Debussy – String Quartet in G minor, op.10

Brahms – String Quartet in A minor, op.51 no.2

Pierre Colombet, Gabriel Le Magadure (violins),

Mathieu Herzog (viola)

Raphaël Merlin (violoncello)

The Quatuor Ebène’s visits to the Wigmore Hall have proved chamber music highlights of their respective seasons for some time now; the present concert did nothing to buck that trend. This was an evening of superlative quartet playing, even by the players’ own exalted standards, a welcome respite from but also challenge to the vile weather currently sweeping the streets of London.

First on was Prokofiev. There is some fine music to his two quartets, especially in this, his first, though it would be difficult to argue that he was the most natural of string quartet composers. Even the key, B minor, is somewhat perverse, as any cellist will tell you. Not that one would have guessed the problems from this performance, in which, the Ebène quite rightly acted as counsel for the defence. The first movement witnessed the identity of the themes and greater structure clearly and keenly delineated. Intriguingly, here and throughout, this was a more highly-strung – if the pun may be forgiven – Prokofiev who emerged than one often hears in his chamber music, partly a matter in this first movement of a fastish tempo but also, crucially, truly dramatic tension. There was excellent, productive contrast between the players acting as soloists and as part of an ensemble, voices emerging therefrom where called upon, and seamlessly blending back into the texture thereafter. Last but not least was a recognition that, in this music as in so much of the rest of his output, Prokofiev’s greatest gift was as a melodist. Then there came as powerful a contrast, without undue exaggeration, as one might wish for between the slow, vaguely Beethovenian introduction to the slow movement and the ‘Vivace’ proper, its thrills as visceral as they were musical. Rhythmic command and ensemble were outstanding, the quartet rightly playing Prokofiev with the abandon and the coherence one would expect in Bartók. This was Prokofiev the modernist with a vengeance, all the more striking since one expects to find him more readily elsewhere. The final ‘Andante’ permitted each player to present – ‘display’ would give entirely the wrong impression – his particular quality to the turning of a melodic phrase, and equally his own individuality of tone. In the broadest of generalisations, one therefore heard the suavity of cellist Raphaël Merlin, the richness of Mathieu Herzog’s viola, the burning intensity of Gabriel Le Magadure on second violin, and a sweet-toned, Cinderella-like lyricism, tinged with Grumiaux-like elegance from Pierre Colombet’s first violin. At least that was the impression at one point, for the changing demands of the music at its more hysterical would at least partially transform those qualities, to highly dramatic effect. Yet above all, this movement was lyrical, in a fashion out of which its form could emerge as naturally as I have yet to hear.

Debussy’s quartet completed the first half. Its first movement opened in a different yet recognisable manner: suavely graceful, the tone more obviously Gallic, though that certainly did not preclude intensity at climaxes. Indeed this could, where appropriate, be Debussy as impassioned as one might hope for – though never more so. Cyclic concision was a hallmark of the entire reading, not least in the transmission of the crucial triplet figure from the first to the second movement, and also of course beyond. That second movement burned with concentrated intensity, albeit with plenty of opportunity, never overlooked, for refreshment in contrast. Unanimity of ensemble never sounded clinical or slick – one can think of a few well-known quartets for whom that would not have been the case – but arose out of straightforwardly excellent, ever-alert quartet-playing. The ‘Andantino’ was given an elegant, sweetly melodic reading, exhibiting a degree of repose, though only relatively so, for it was no less attentive than any other movement to the relationship between detail and the whole. An urgent but satisfying cyclic unification marked the finale, movement and work becoming much more than the sum of their parts. Everything fell into place, though not bureaucratically; it was more a matter of ultimate victory for an Apollonian imperative.

Brahms’s second quartet was heard after the interval. Again, the sonority one heard could be characterised as different and yet the same. (I thought of Hans Sachs advising Walther that a song cannot always be for spring.) The general sound was more deeply Germanic, as one would expect, yet remained blessed by the elegance and clarity the best Franco-Flemish players have often brought to this repertoire. There was more than a hint of Schubert’s ‘Rosamunde’ Quartet, perhaps especially to the first movement’s second subject, though the motivic working unsurprisingly emerged more tightly-knit. Throughout, the players showed themselves heedful of Brahms’s melodic impulse, which engenders its own passions; there is no need to apply anything from without. Again, the Classical and Romantic were held in well-judged balance and tension during the second movement: not in some abstract equilibrium, but according to the particular needs of the material. The relative minor’s intervention was impassioned and not without influential, but the intermezzo-like mood ultimately if uneasily prevailed. Brahms’s Beethovenian inheritance was readily felt in the alternating, conflicting material of the third movement, vividly dramatised. There was even a hint of Haydn in the faster scherzo music, though Schubert again proved the principal ghost in its more wistful counterpart. The finale made clear that, as ever with Brahms, any ‘Hungarian’ colouring is just that: colouring. The real battle to be fought is ‘German’, through and through, its contrapuntal travails here evoking Beethoven and Bach, whilst inevitably looking forward also to Schoenberg. There was charm too, of an undeniably Viennese variety, though tragedy would out.

Sunday, 11 December 2011

Bavouzet/Philharmonia/Ashkenazy - Dukas, Ravel, Falla, and Debussy, 11 December 2011

Royal Festival Hall

Dukas – L’apprenti sorcier

Ravel – Piano Concerto in G major

Falla – Noches en los jardines de España

Debussy – La mer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (piano)

Philharmonia Orchestra

Vladimir Ashkenazy

All too often, one witnesses a thoughtless reflex reaction directed toward pianists-turned-conductors. Maurizio Pollini suffered considerable hostility on beginning to conduct; the experience appears to have put him off for good, save for directing Mozart concertos from the piano. One sometimes still hears people say they wish that Daniel Barenboim would concentrate upon the piano, apparently oblivious to how much his conducting has enriched his performances at the keyboard, and vice versa. Vladimir Ashkenazy presents a more difficult case: clearly he is not a bad conductor, as some instrumentalists or singers have proved, but it would be difficult to argue that he has enjoyed similar success in that role as he did as a pianist. One can imagine, though, how much a pianist might value having him as a concerto ‘accompanist’, knowing so many works as a pianist himself. Ashkenazy presents such a genial, collegiate personality on the stage that one cannot help but wish him well; however, my experience on this occasion, as in the past, turned out to be mixed.

Dukas’s scherzo, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, received a disappointing performance. Following slight rhythmic hesitancy at the opening – on Ashkenazy’s part, rather than the Philharmonia’s – the conductor seemed to over-compensate, imparting thereafter a frankly brutal drive, which never relented. The mechanical entirely supplanted the fantastical; a smile was nowhere to be heard.

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet then joined the orchestra for two works, the first being Ravel’s G major Piano Concerto. The elegant ease with which Bavouzet despatched the opening piano flourishes was something to savour. Throughout the first movement, he remained alert to Ravel’s twists and turns – and, crucially, to their motivations. Ashkenazy’s handling of the orchestral music was less sure: there were a few minor imprecisions. More seriously, he was often too much the mere ‘accompanist’, following but never really leading. There was nevertheless a great deal to enjoy in the bluesy solos so evidently relished by various Philharmonia principals. The lengthy opening piano solo to the slow movement was not just exquisitely shaped but intriguingly alert to darker undercurrents, Bavouzet bringing the mood a little closer to that of the Left Hand Piano Concerto than s generally the case. Here and later on, his playing was full of subtle shading and phrasing. Again, there was some very fine woodwind playing, not least from Jill Crowther on English horn. The finale I found more problematic. It received a brisk, no-nonsense reading that rather lacked charm: Bavouzet’s delivery, followed by Ashkenazy’s, seemed at times closer to Prokofiev than to Ravel in its muscular approach. There were no such problems, however, with his encore, a darkly atmospheric account of Debussy’s ‘La puerta del Vino’ from the second book of Préludes. Rhythmic insistence was somehow combined with subtle and supple variation.

That ‘Spanish’ piece also offered a good link to the two pieces in the second half: Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain and Debussy’s own La mer. Ashkenazy’s conducting seemed much sharper in the Falla: full of energy and with a considerably broader colouristic range, those two facets well integrated. Indeed, both he and Bavouzet moved convincingly between languor and biting precision in the first movement, ‘En el Generalife’. The Philharmonia’s cello section was on especially fine form, but all the strings, indeed all the orchestra, contributed to a tremendous climax. The second movement, ‘Danza lejana’, was equally well judged: atmospheric, yet not at the cost of melodic and rhythmic definition. There was a true sense of dialogue now between piano and orchestra, similarly in the final movement, ‘En los jardines de la Sierra de Córdoba’, though occasionally I wondered whether it was a touch on the driven side. I am not sure that the movement presents Falla at his most distinguished, but it received a fine performance nonetheless.

La mer had much to offer too. The outer movements received for the most part eminently musicianly readings, though I have heard saltier accounts. No matter: there were some beautifully hushed moments and Ashkenazy conveyed an impressive degree of quasi-symphonic logic throughout, which, if anything became more pronounced during the course of the first movement. I do not recall a performance in which the presence of Franck has been so pronounced. Ashkenazy reinstated the brass fanfares at the conclusion of ‘De l’aube à midi sur la mer’. (I approve, though some do not.) ‘Jeux de vagues’ offered glitter but purpose too, precision but not too much, its mystery retained. What I missed, and this registered most strongly in the final movement, was a sense of Debussy’s modernity. This was, broadly speaking, Debussy emerging from the nineteenth century – Liszt, Tchaikovsky, and Borodin all sprang to mind – rather than the progenitor of Messiaen and Boulez. There is room for both approaches, of course, and doubtless for others too, though the final climax proved surprisingly brash. A little more refinement there would not have gone amiss.

Dukas – L’apprenti sorcier

Ravel – Piano Concerto in G major

Falla – Noches en los jardines de España

Debussy – La mer

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet (piano)

Philharmonia Orchestra

Vladimir Ashkenazy

All too often, one witnesses a thoughtless reflex reaction directed toward pianists-turned-conductors. Maurizio Pollini suffered considerable hostility on beginning to conduct; the experience appears to have put him off for good, save for directing Mozart concertos from the piano. One sometimes still hears people say they wish that Daniel Barenboim would concentrate upon the piano, apparently oblivious to how much his conducting has enriched his performances at the keyboard, and vice versa. Vladimir Ashkenazy presents a more difficult case: clearly he is not a bad conductor, as some instrumentalists or singers have proved, but it would be difficult to argue that he has enjoyed similar success in that role as he did as a pianist. One can imagine, though, how much a pianist might value having him as a concerto ‘accompanist’, knowing so many works as a pianist himself. Ashkenazy presents such a genial, collegiate personality on the stage that one cannot help but wish him well; however, my experience on this occasion, as in the past, turned out to be mixed.

Dukas’s scherzo, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, received a disappointing performance. Following slight rhythmic hesitancy at the opening – on Ashkenazy’s part, rather than the Philharmonia’s – the conductor seemed to over-compensate, imparting thereafter a frankly brutal drive, which never relented. The mechanical entirely supplanted the fantastical; a smile was nowhere to be heard.

Jean-Efflam Bavouzet then joined the orchestra for two works, the first being Ravel’s G major Piano Concerto. The elegant ease with which Bavouzet despatched the opening piano flourishes was something to savour. Throughout the first movement, he remained alert to Ravel’s twists and turns – and, crucially, to their motivations. Ashkenazy’s handling of the orchestral music was less sure: there were a few minor imprecisions. More seriously, he was often too much the mere ‘accompanist’, following but never really leading. There was nevertheless a great deal to enjoy in the bluesy solos so evidently relished by various Philharmonia principals. The lengthy opening piano solo to the slow movement was not just exquisitely shaped but intriguingly alert to darker undercurrents, Bavouzet bringing the mood a little closer to that of the Left Hand Piano Concerto than s generally the case. Here and later on, his playing was full of subtle shading and phrasing. Again, there was some very fine woodwind playing, not least from Jill Crowther on English horn. The finale I found more problematic. It received a brisk, no-nonsense reading that rather lacked charm: Bavouzet’s delivery, followed by Ashkenazy’s, seemed at times closer to Prokofiev than to Ravel in its muscular approach. There were no such problems, however, with his encore, a darkly atmospheric account of Debussy’s ‘La puerta del Vino’ from the second book of Préludes. Rhythmic insistence was somehow combined with subtle and supple variation.