Philharmonie

Rameau:

Les

Indes Galantes: Suite

Lachenmann:

Mouvement (– vor der Erstarrung)

Berlioz: Harold en Italie, op.16

Tabea Zimmermann (viola)

Les Siècles

François-Xavier Roth (conductor)

|

| Images: © Monika Karczmarczyk |

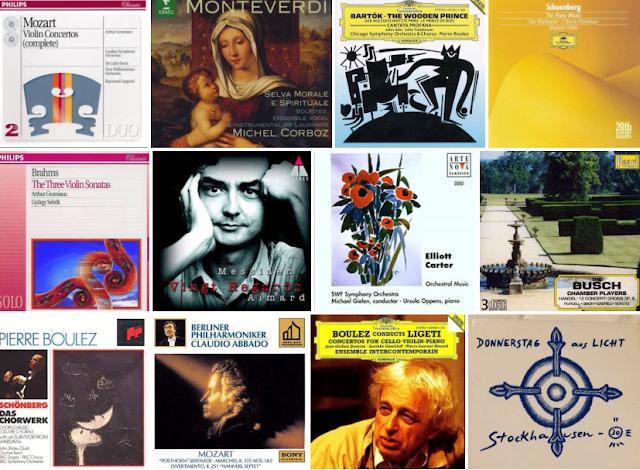

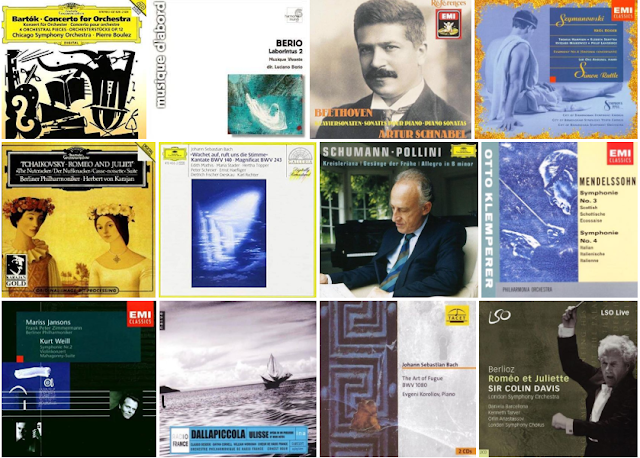

Charles Ives’s father

famously insisted that his son stretch his ears. It was partly in that spirit

that I went to this concert from the French period-instrument orchestra, Les

Siècles, and its founder, François-Xavier

Roth. Hand on heart, I remain a sceptic, though certainly not an opponent, when

it comes to period instruments. I reacted very strongly against them, or rather

against the underlying ideologies of those preaching their use, when coming of

musical age. No one was successfully going to tell this teenager that he could

not play Bach – or Handel, or Rameau, or Byrd… – on the piano; no one likewise

was going to create anything other than an enemy by telling him the Bach of

Klemperer or Furtwängler or, God help us, even Karl Richter was ‘incorrect’, or

as Gustav Leonhardt put it in the case of Furtwängler, ‘disgusting’. (To be

fair, ‘disgusting’ at least shows some emotional engagement; the idea of a

performance being ‘correct’ or ‘incorrect’ is considerably worse.) However, not

everyone is like that, especially today; many ‘period’ musicians indeed never

were. Partly through curiosity, partly through friendship with many musicians

with varying degrees of commitment to such music-making, and partly through re-examination

of my own prejudices and that imperative to stretch my ears, I have latterly

shown greater interest and sympathy.

When it comes, say, to

seventeenth-century music, I frankly have little choice, if I ever want to hear

that music performed live. With the eighteenth-century, opportunities to hear

its music on modern instruments vary according to repertoire and instrument: pianists

are clearly never going to give up Bach, yet how often do we hear a symphony or

even chamber orchestra perform a Handel oratorio that is not Messiah, let alone a Rameau opera? The

nineteenth century is another matter again; I have never felt any particular

need here, but curiosity led me here to give Berlioz on instruments of the

period. So too did the ethos of the orchestra in question: that is, playing

each piece, as close as possible, on the instruments of its time, thus

affording a contrast between instruments of the mid-eighteenth, mid-nineteenth,

and the late twentieth centuries. So too did the programme – how often, if

ever, have Rameau, Lachenmann, and Berlioz appeared together like this? – and the

conductor, whose work I have long admired. Why mention all of this? I hope that

is not simply self-absorption, but also to try to explain what will perhaps be

an unusually personal response. My aim is certainly not to dissuade musicians from

performing and listeners from listening to Berlioz on period instruments – why on

earth should I wish to do that? – but to describe and also to reflect a little

on my experience. By all means call me an antediluvian, if it helps – whilst

also acknowledging the ‘historicist’ irony that may entail.

First, however, Rameau, and a

suite from Les Indes galantes

(instruments of 1750, A=415 Hz). As it happens, I had actually heard another

suite from the same opera on modern instruments (LSO/Rattle)

earlier this year. I had also, once before, heard Roth conduct Rameau dances, albeit from Dardanus,

with a modern orchestra (the BBC NOW), at the Proms. If my prejudices may lie

in that direction, I am not at all sure that this was not the best performance

of the three. It certainly left me in no doubt that I was happy to listen to

this music on instruments of any period, which would doubtless have surprised

my younger self. Roth and his players, mostly standing with obvious exceptions,

offered an introduction, the ‘Entrée de la suite d’Hébée’, as enticing and in

its way as fantastical as anything in Berlioz: an array of percussion,

responded to by light, lithe, yet far from inexpressive or indeed vibrato-less

playing. It set an infectious precedent, to which subsequent dances fully lived

up. Two rigaudons (‘pour les Matelots provençaux et Matelotes provençales’) both offered expressive lilt and meaningful contrast, both with what had come and

with each other. Here and in the pair of tambourins (also for those Provencal

sailors) one could pretty much see the dancers in one’s mind’s eyes, fully

alert to the dramatic possibilities of the dance’s intensification on repetition

(and dynamic variation). Two numbers in common with Rattle’s selection, music

for the ‘savages’ and the great chaconne, brought the suite to a memorable

conclusion, the latter’s sequential sense of drama firmly founded in rhythm and

harmony. Indeed, it was Raymond Leppard, rather than any period-instrument

conductor, who came to mind for me. Not that these instruments lacked their own

character and colour, in many respects delightful, but those were not ends in

themselves.

Lachenmann’s Mouvement ( – vor der Erstarrung) for

ensemble dates from almost two-and-a-half centuries after Rameau’s opera

(1982-4, as opposed to 1735). It was played on modern instruments, or, as the

programme had it, ‘instruments from the year 1980’, tuning at A=442. This was

at least as committed a performance, not only revealing something akin to a

sonic palimpsest, but also revelling in the drama of effort in music-making, as

well as its reward, by players truly in sovereign command of their instruments.

Webern and Nono, as in the Tanzsuite mit

Deutschlandlied heard that morning, were present guests at the feast, yet

in no sense could any of the music have been said to sound like theirs; rather,

their methods, or memories thereof, helped us – or at least me – find a way in.

Extreme ‘expressivity’ – I am not sure that that is quite the right word – of

twin precision and intensity bade, even insisted, that one listen, and listen

with ears both old and new: an idea not without implications for such an

orchestra and such a programme. I could even have sworn I heard a Rameau rhythm

echoed at one point: a coincidence at best, yet a pleasing one. Lachenmann’s

music was played with all the skill and understanding of a dedicated new music

ensemble, but does this music, the best of forty years all, still qualify as ‘new

music’? Does it matter? Eruptions as powerful as those in Mahler (or Webern),

whispered confidences as hyper-expressive as those of Nono, riots of wind and

percussion to rival Messiaen’s: those and many other aspects, moments, of

death, yet also surely in some sense of life, offered a world-kaleidoscope different

from Rameau’s, yet one which could surely be heard with profit in succession to

it. A performance exhilarating in its aggression had me ask whether my ears

would ever be quite the same again, and why on earth I should wish them to be.

Finally, then, Berlioz, and Harold en Italie (instruments from 1850,

A=438), for which the orchestra was joined by Tabea Zimmermann. I learned much

from the performance, yet emerged from it less convinced. That may simply, or

principally, be more a matter of my resistance; perhaps I was hearing it not

dissimilarly from the way some notably dissatisfied members of the audience

appeared to have heard Lachenmann. Perhaps that was no bad thing at all. Certainly

the darker, less resonant string tone with which the first movement opened, had

its own potentialities. It was woodwind blend, or lack thereof, both within the

section and with the strings, that troubled me more. That will doubtless have

been part of the attraction for many, but I found it had me listen more to the

instruments, less to what they played. On her entry, Zimmermann proved unfussy

yet expressive; so too was the harpist with whom she duetted. (The idea of

placing the harp at the front of the stage, almost as a second soloist, offered

a definite advantage here.) As time went on, though, Zimmermann proved surprisingly

wayward, not just of mood, but of tuning, a problem far from restricted to this

movement. Roth’s basic tempo was faster than usual, but it worked well, and was

far from inflexible. If a relative thinness of orchestral tone contrasted greatly

with Roméo et Juliette from the Berlin

Philharmonic just two nights previously, stretching my ears was always intended

as part of the exercise.

For the second movement, I was

gain struck by the difference in balance and blend. The mood was very

different, too, from any performance I could recall: less solemn, more a motley

crew of pilgrims. Why not? Again, it made me listen, and there was something

quite Catholic, even if renegade Catholic, to the conception, which fitted

well. The mountaineer serenading his beloved in the third movement benefited

from splendidly rustic sound, period woodwind here coming into its own (for me,

at any rate), in what proved another swift account. There was plenty of nervous

energy to the finale, whose darker colours and moods came off best, Roth

handling its many twists and turns with typical skill and conviction. There

were some pretty wild sounds, all in all: many will have found them exciting;

alas, they soon became rather wearing for me. I suspect they would have done so

still more on repetition. As an encore, the ‘Marche hongroise’ from La Damnation de Faust proved infinitely

more colourful and involving than it had during a dreary trudge on modern instruments

through the entire work at Glyndebourne this summer with Robin Ticciati. Swings and roundabouts, then; I had at any rate stretched

my ears and been made to think.