This double 'Bank Holiday Weekend', with apologies to non-British readers whom it does not affect, has brought little musical cheer. The musical choices for yesterday's Royal Wedding ranged from Last Night of the Proms-style Walton and Elgar to the truly execrable, Westminster Abbey's gift to the happy couple being an anthem by John Rutter. (Whatever would the Royal Peculiar inflict upon those it dis-liked?!) Sadly, the hope that had promised to sustain some of us through a day of fatuous 'commentary' - 'We can exclusively reveal that so-and-so is a relatively approachable person and sometimes remembers servants' birthdays', etc. - had already been denied, influenza having caused Maurizio Pollini to postpone his evening recital at the Royal Festival Hall. No Boulez second piano sonata, then, until June...

To lift the Boulezian spirits, then, however vain the hopes, another coda to the Fantasy Opera season (which opened here): a non-partisan, first-past-the-post readers' poll. The following twenty operas present but a meagre selection, of course, and the choice is shamelessly a reflection of a few works that would interest me, but there is only one work per composer and I hope that there will be something for everyone. For what it is worth, I should be very happy with any of them. So far as I am aware, the Royal Opera has never staged any of these works. And if it has, so be it: our fantasy house can do so again. Which would you select to feature next season? (And feel free to substitute your own house, real or imaginary, for Covent Garden, should that make more sense.) Readers are kindly invited to cast their votes; otherwise my musical misery will only continue...

(P.S. Apologies for the misspelled 'Sonntag' on the results display; I cannot work out how that happened, since it reads correctly on the present page. At any rate, I have no idea how to alter it. Sirius may or may not prove forgiving...)

Saturday, 30 April 2011

Thursday, 28 April 2011

Konstantin Lifschitz - Bach, Art of Fugue, 28 April 2011

Wigmore Hall

The only other time I can recall that I have heard the complete Art of Fugue in concert was also at the Wigmore Hall, in a performance given a little over two years ago by Pierre-Laurent Aimard (click here). Aimard’s performance had its strengths, but also had its weaknesses, not least that it sometimes seemed more of a lecture than a performance. At the time I mused, as a consequence of a curiously unsatisfying experience: ‘One might claim that any performance of Bach’s Art of Fugue is bound to fall short, especially given the uncertainties attendant to all issues regarding performance (even, for a few, its desirability). Yet one could with more or less equal justice claim the opposite, namely that Bach’s contrapuntal compendium should be able to satisfy like almost nothing else, at least if one leaves aside its lack of completion.’ If Aimard led me to lean towards the former option, Konstantin Lifschitz left me with no doubt whatsoever that Bach’s summa might satisfy like nothing else; his was a truly outstanding performance, with which I could find nothing whatsoever to quibble, an extraordinary outcome given the number of plausible, let alone possible, options for performance.

The only feeling that might have approximated to doubt arose with Lifschitz’s una corda rendition of Contrapunctus I. Yet use of the soft pedal, which might often have seemed mannered, soon came to seem beside the point in a performance that somehow sounded, and not only because Lifschitz began before the opening applause had subsided, as though it began in medias res. It was as if what was going on had always been going on, prompting – as the performance did throughout – philosophical speculation. Is this the pre-Socratic, monistic thought of Parmenides that what has always been must continue to be, and that change is therefore impossible? Not at all, once one thinks, or listens; rather it is the Christian: ‘As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end, Amen.’

Contrapunctus II came as a surprising contrast, opening in almost unrelenting fortissimo, redolent if abstracted from the particular performance, of Mussorgsky’s Bydlo. But the point is that, abstract as the music may be, it is not abstracted. Everything had its place under Lifschitz’s hands, so much that I began to think about Bach as a musical equivalent to great scholastic schemes such as that of St Thomas Aquinas – only surpassing them in every respect. Not for nothing did Lifschitz’s rhythmic surety point towards the late Beethoven of the op.111 sonata and the Diabelli Variations, whilst remaining faithful to Bachian musical science ( the German Wissenschaft so much more broadly construed than modern English ‘science’). Everything was to be heard in what followed, or so it seemed. Extraordinary pianistic delicacy and fugues seemingly led by ‘modern’ harmonic concerns mixed shoulders with, or rather interacted with, stile antico deliberation that yet revealed the music’s inner workings upon the outside, not unlike the Centre Pompidou, home of IRCAM. (It is no coincidence that Boulez conducted this very work during his Domaine musical years, nor that a modernist pianist such as Aimard has shown himself so attracted to it.) In Contrapunctus V, one could hear Byrd and Chopin – yet at the same time only Bach. The stile francese of Contrapunctus VI immediately brought to mind yet immediately surpassed Couperin, whilst its pianistic conclusion summoned the ghost – or should that be a premonition – of Busoni, who needless to say, reappeared in the supreme consolation of the closing chorale, ‘Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit!’

In between, however, there was much more to hear, as thoughts began to wander from Aquinas to the more dynamic form of Aristotelian ontology, relieved of scholastic encrustation, offered by Hegel – not that ideas of Platonic forms deserted one either. Augmentation and diminution were not only observed but fully experienced, not merely displayed but heard to be absolutely necessary, in a dialectic between freedom and organisation that pointed to and yet beyond Kant. Bergian chromaticism, even Birtwistle’s labyrinth, could be discerned, without the slightest doubt that Bach remained himself throughout. Lifschitz’s magnificent, unforced command of cumulative power, both within fugues and throughout the ‘work’ as a whole, was crucial to this and to much else. Fury could be expressed, but never inappropriately, and never at the cost – so readily paid by many – of sounding hard-driven. Likewise limpidity moved one beyond tears, without the slightest hint of sentimentality. This was music both for and beyond the piano, shimmering Romanticism and old-fashioned organ-reed registration dissolving or sublating themselves seamlessly into abstraction that yet reached beyond abstraction. No sooner had one heard elements of a gigue-like dance then one knew that this was no mere dance: modern ‘authenticist’ reductionism completely misses the point here, as in so much else. But such thoughts concerning other schools of performance only occurred later: at the time, one heard Bach, and only Bach, and believed that there could be nothing else.

I shall be astonished if this does not prove to be one of my performances of the year. Bach remains the Alpha and the Omega of music; a performance that proves worthy of him is distinguished indeed.

The only other time I can recall that I have heard the complete Art of Fugue in concert was also at the Wigmore Hall, in a performance given a little over two years ago by Pierre-Laurent Aimard (click here). Aimard’s performance had its strengths, but also had its weaknesses, not least that it sometimes seemed more of a lecture than a performance. At the time I mused, as a consequence of a curiously unsatisfying experience: ‘One might claim that any performance of Bach’s Art of Fugue is bound to fall short, especially given the uncertainties attendant to all issues regarding performance (even, for a few, its desirability). Yet one could with more or less equal justice claim the opposite, namely that Bach’s contrapuntal compendium should be able to satisfy like almost nothing else, at least if one leaves aside its lack of completion.’ If Aimard led me to lean towards the former option, Konstantin Lifschitz left me with no doubt whatsoever that Bach’s summa might satisfy like nothing else; his was a truly outstanding performance, with which I could find nothing whatsoever to quibble, an extraordinary outcome given the number of plausible, let alone possible, options for performance.

The only feeling that might have approximated to doubt arose with Lifschitz’s una corda rendition of Contrapunctus I. Yet use of the soft pedal, which might often have seemed mannered, soon came to seem beside the point in a performance that somehow sounded, and not only because Lifschitz began before the opening applause had subsided, as though it began in medias res. It was as if what was going on had always been going on, prompting – as the performance did throughout – philosophical speculation. Is this the pre-Socratic, monistic thought of Parmenides that what has always been must continue to be, and that change is therefore impossible? Not at all, once one thinks, or listens; rather it is the Christian: ‘As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end, Amen.’

Contrapunctus II came as a surprising contrast, opening in almost unrelenting fortissimo, redolent if abstracted from the particular performance, of Mussorgsky’s Bydlo. But the point is that, abstract as the music may be, it is not abstracted. Everything had its place under Lifschitz’s hands, so much that I began to think about Bach as a musical equivalent to great scholastic schemes such as that of St Thomas Aquinas – only surpassing them in every respect. Not for nothing did Lifschitz’s rhythmic surety point towards the late Beethoven of the op.111 sonata and the Diabelli Variations, whilst remaining faithful to Bachian musical science ( the German Wissenschaft so much more broadly construed than modern English ‘science’). Everything was to be heard in what followed, or so it seemed. Extraordinary pianistic delicacy and fugues seemingly led by ‘modern’ harmonic concerns mixed shoulders with, or rather interacted with, stile antico deliberation that yet revealed the music’s inner workings upon the outside, not unlike the Centre Pompidou, home of IRCAM. (It is no coincidence that Boulez conducted this very work during his Domaine musical years, nor that a modernist pianist such as Aimard has shown himself so attracted to it.) In Contrapunctus V, one could hear Byrd and Chopin – yet at the same time only Bach. The stile francese of Contrapunctus VI immediately brought to mind yet immediately surpassed Couperin, whilst its pianistic conclusion summoned the ghost – or should that be a premonition – of Busoni, who needless to say, reappeared in the supreme consolation of the closing chorale, ‘Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich hiermit!’

In between, however, there was much more to hear, as thoughts began to wander from Aquinas to the more dynamic form of Aristotelian ontology, relieved of scholastic encrustation, offered by Hegel – not that ideas of Platonic forms deserted one either. Augmentation and diminution were not only observed but fully experienced, not merely displayed but heard to be absolutely necessary, in a dialectic between freedom and organisation that pointed to and yet beyond Kant. Bergian chromaticism, even Birtwistle’s labyrinth, could be discerned, without the slightest doubt that Bach remained himself throughout. Lifschitz’s magnificent, unforced command of cumulative power, both within fugues and throughout the ‘work’ as a whole, was crucial to this and to much else. Fury could be expressed, but never inappropriately, and never at the cost – so readily paid by many – of sounding hard-driven. Likewise limpidity moved one beyond tears, without the slightest hint of sentimentality. This was music both for and beyond the piano, shimmering Romanticism and old-fashioned organ-reed registration dissolving or sublating themselves seamlessly into abstraction that yet reached beyond abstraction. No sooner had one heard elements of a gigue-like dance then one knew that this was no mere dance: modern ‘authenticist’ reductionism completely misses the point here, as in so much else. But such thoughts concerning other schools of performance only occurred later: at the time, one heard Bach, and only Bach, and believed that there could be nothing else.

I shall be astonished if this does not prove to be one of my performances of the year. Bach remains the Alpha and the Omega of music; a performance that proves worthy of him is distinguished indeed.

Berlin Staatsoper season, 2011-12

Just in: a press release, reproduced below, introducing the next season from Daniel Barenboim and Jürgen Flimm. The Chéreau/Rattle From the House of the Dead is an obvious attraction for those, like myself, yet to see the production, the one preserved on an Aix DVD, conducted by Boulez . So is the Breth/Barenboim Lulu, to which I referred in my earlier Wozzeck review. Nono's Al gran sole carico d'amore looks as though it will be the excellent Salzburg production (reviewed here). Achim Freyer will doubtless bring his inimitable - at least I hope so - one-clown-size-fits-all approach to Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo. The visiting Scala Don Giovanni looks very attractive; when I heard Barenboim conduct the short-lived Peter Mussbach production (click here), it was far and away the best live account of the score I had experienced, and still is. Cage fans and doubtless even interested sceptics - I probably fall into the latter camp - will be intrigued by the promised Cage cycle. The list of solo performers looks mouth-watering too, from Pollini to Mutter.

. So is the Breth/Barenboim Lulu, to which I referred in my earlier Wozzeck review. Nono's Al gran sole carico d'amore looks as though it will be the excellent Salzburg production (reviewed here). Achim Freyer will doubtless bring his inimitable - at least I hope so - one-clown-size-fits-all approach to Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo. The visiting Scala Don Giovanni looks very attractive; when I heard Barenboim conduct the short-lived Peter Mussbach production (click here), it was far and away the best live account of the score I had experienced, and still is. Cage fans and doubtless even interested sceptics - I probably fall into the latter camp - will be intrigued by the promised Cage cycle. The list of solo performers looks mouth-watering too, from Pollini to Mutter.

PRESS RELEASE

Berlin, 28 April 2011

Jürgen Flimm and Daniel Barenboim present the Staatsoper programme for the second season at the Schiller Theater. This week artistic director Jürgen Flimm and general music director Daniel Barenboim presented the programme for the 2011/2012 season, the Staatsoper’s second at the Schiller Theater.

The 2011/2012 season will feature eight opera premieres on the main stage, as well as six additional premieres on the Werkstatt studio stage. Furthermore there will be one guest production, two operatic concerts, 19 operas from the repertoire, over 80 concerts, the annual FESTTAGE series at Easter, the second year of the INFEKTION! festival of contemporary music theater, one premiere and four repertoire productions by the Staatsballett Berlin, a continuation of the Schlaflos in Charlottenburg series in the foyer as well as numerous projects by the Junge Staatsoper. The Staatsoper’s programme comprises a total of 370 events.

The season will open on 3 October 2011 with Leoš Janáček’s From the House of the Dead staged by Patrice Chéreau and conducted by Simon Rattle as conductor. Following her Wozzeck production in 2011, Andrea Breth will direct Alban Berg´s Lulu for the 2012 FESTTAGE, once again with Daniel Barenboim conducting. Further premieres will be The Bartered Bride by Bedřich Smetana (Karl-Heinz Steffens / Balász Kovalik), Orpheus in the Underworld by Jacques Offenbach in a new production by Christoph Israel and Thomas Pigor (text) (Christoph Israel / Philipp Stölzl), Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno by Georg Friedrich Händel (Marc Minkowski / Jürgen Flimm), Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo by Emilio de’ Cavalieri (René Jacobs / Achim Freyer) and Dionysos by Wolfgang Rihm (Ingo Metzmacher / Pierre Audi). With the premiere of Luigi Nono’s Al gran sole carico d´amore (Ingo Metzmacher / Katie Mitchell), the Staatsoper will open a new venue, namely the “Kraftwerk Mitte”, a former power station. A guest production of the Teatro alla Scala di Milano will see Daniel Barenboim conducting Mozart’s Don Giovanni – with Anna Netrebko and Christopher Maltman. In addition two operas in concert form will be presented: Montezuma by Carl Heinrich Graun with Vesselina Kasarova and Pavol Breslik, and Bellini’s Norma with Edita Gruberova, Sonia Ganassi and Johan Botha.

Additional outstanding guest artists in the Staatsoper’s coming season at the Schiller Theater include Plácido Domingo, Rolando Villazón, Mojca Erdmann, Waltraud Meier, Anja Harteros, Erwin Schrott, Giuseppe Filianoti, Deborah Polaski, Michael Volle, Magdalena Kožená, Georg Nigl, Kristine Opolais and Pavel Černoch.

Daniel Barenboim will conduct the Staatskapelle in four concert programmes as well as the traditional New Year’s concert, two charity events for the reconstruction of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, a gala concert celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Jewish MuseumBerlin, and three symphony concerts with both the Staatskapelle and the Filarmonica dellaScala as part of the FESTTAGE 2012. The concert soloists include Anna Netrebko, Elīna Garanča, Anne-Sophie Mutter, Alisa Weilerstein, Jonas Kaufmann, Maurizio Pollini and Radu Lupu. The Barenboim Cycle will offer collaborations with Christine Schäfer, Dorothea Röschmann and Thomas Quasthoff. A song recital by René Pape with Daniel Barenboim as accompanying pianist is a set part of the 2012 FESTTAGE. The Staatsoper will also present a six-part piano cycle featuring Daniel Barenboim, the young Chinese pianist Yuja Wang as well as András Schiff and Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

Two conductors who recently debuted with the Staatskapelle, Pietari Inkinen and Andris Nelsons, will return. Kirill Petrenko, another new-generation conductor, will lead the orchestra as a guest for the first time. Principal guest conductor Michael Gielen will conduct a symphony concert. Three song recitals with Anna Prohaska, Bejun Mehta and Ian Bostridge, in addition to a Baroque concert under the direction of Marc Minkowski, will further enrich the programme at the Schiller Theater. The chamber music series, successfully launched last season at the Rotes Rathaus (Berlin City Hall) and the Bode Museum, will be continued. The Werkstatt studio stage at the Schiller Theater, whose first season last year was enthusiastically received as a venue for innovative musical theater in Berlin, will present a John Cage cycle entitled Die Musik ist los – 100 Jahre Cage as part of the INFEKTION! festival, in addition to five premieres and one revival: Lucia Ronchetti’s Last Desire based on Oscar Wilde’s Salome, Manfred Stahnke’s Wahnsinn, das ist die Seele der Handlung based on texts by Edgar Allan Poe, Lehrstück by Paul Hindemith and Bertolt Brecht, and the Junge Staatsoper’s productions of Aschenputtel (Cinderella) by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari and Moskau Tscherjomuschki, a musical comedy by Dmitri Shostakovich. Following more than 40 soldout performances, the opera Der gestiefelte Kater by César Cui is once again on the programme. The highly successful “Satie” evening Wissen Sie, wie man Töne reinigt? Satiesfactionen – with actors Jan Josef Liefers, Stefan Kurt and Klaus Schreiber – will also be revived.

And finally, the Staatsoper will return both this year and next year to the Bebelplatz. Against the backdrop of the opera building Unter den Linden, as impressive as ever despite reconstruction work, we are looking forward to celebrating STAATSOPER FÜR ALLE with many thousands of visitors - made possible by our partner BMW Berlin. On Sunday 26 June 2011 at 1:00 pm, Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin will perform an open-air concert. On 30 June 2012 the performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni with Anna Netrebko at the Schiller Theater will be shown live on wide screens on the Bebelplatz, followed on 1 July 2012 by a concert with Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin.

The complete 2011/2012 programme and all information is now online at: http://www.staatsoperberlin.de/.

Advance sales for all performances of the 2011/2012 season will begin on 14 May 2011.

Subscription sales start on 30 April 2011. FESTTAGE 2012 cycle tickets are on sale now.

Members of the Staatsoper Association (Förderverein), subscribers and StaatsopernCard holders enjoy advance purchase rights for all performances starting on 7 May 2011.

Tickets are available online at http://www.staatsoper-berlin.de/, by phone at 0049 30 20 35 45 55 and at the Staatsoper box office at the Schiller Theater.

PRESS RELEASE

Berlin, 28 April 2011

Jürgen Flimm and Daniel Barenboim present the Staatsoper programme for the second season at the Schiller Theater. This week artistic director Jürgen Flimm and general music director Daniel Barenboim presented the programme for the 2011/2012 season, the Staatsoper’s second at the Schiller Theater.

The 2011/2012 season will feature eight opera premieres on the main stage, as well as six additional premieres on the Werkstatt studio stage. Furthermore there will be one guest production, two operatic concerts, 19 operas from the repertoire, over 80 concerts, the annual FESTTAGE series at Easter, the second year of the INFEKTION! festival of contemporary music theater, one premiere and four repertoire productions by the Staatsballett Berlin, a continuation of the Schlaflos in Charlottenburg series in the foyer as well as numerous projects by the Junge Staatsoper. The Staatsoper’s programme comprises a total of 370 events.

The season will open on 3 October 2011 with Leoš Janáček’s From the House of the Dead staged by Patrice Chéreau and conducted by Simon Rattle as conductor. Following her Wozzeck production in 2011, Andrea Breth will direct Alban Berg´s Lulu for the 2012 FESTTAGE, once again with Daniel Barenboim conducting. Further premieres will be The Bartered Bride by Bedřich Smetana (Karl-Heinz Steffens / Balász Kovalik), Orpheus in the Underworld by Jacques Offenbach in a new production by Christoph Israel and Thomas Pigor (text) (Christoph Israel / Philipp Stölzl), Il Trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno by Georg Friedrich Händel (Marc Minkowski / Jürgen Flimm), Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo by Emilio de’ Cavalieri (René Jacobs / Achim Freyer) and Dionysos by Wolfgang Rihm (Ingo Metzmacher / Pierre Audi). With the premiere of Luigi Nono’s Al gran sole carico d´amore (Ingo Metzmacher / Katie Mitchell), the Staatsoper will open a new venue, namely the “Kraftwerk Mitte”, a former power station. A guest production of the Teatro alla Scala di Milano will see Daniel Barenboim conducting Mozart’s Don Giovanni – with Anna Netrebko and Christopher Maltman. In addition two operas in concert form will be presented: Montezuma by Carl Heinrich Graun with Vesselina Kasarova and Pavol Breslik, and Bellini’s Norma with Edita Gruberova, Sonia Ganassi and Johan Botha.

Additional outstanding guest artists in the Staatsoper’s coming season at the Schiller Theater include Plácido Domingo, Rolando Villazón, Mojca Erdmann, Waltraud Meier, Anja Harteros, Erwin Schrott, Giuseppe Filianoti, Deborah Polaski, Michael Volle, Magdalena Kožená, Georg Nigl, Kristine Opolais and Pavel Černoch.

Daniel Barenboim will conduct the Staatskapelle in four concert programmes as well as the traditional New Year’s concert, two charity events for the reconstruction of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden, a gala concert celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Jewish MuseumBerlin, and three symphony concerts with both the Staatskapelle and the Filarmonica dellaScala as part of the FESTTAGE 2012. The concert soloists include Anna Netrebko, Elīna Garanča, Anne-Sophie Mutter, Alisa Weilerstein, Jonas Kaufmann, Maurizio Pollini and Radu Lupu. The Barenboim Cycle will offer collaborations with Christine Schäfer, Dorothea Röschmann and Thomas Quasthoff. A song recital by René Pape with Daniel Barenboim as accompanying pianist is a set part of the 2012 FESTTAGE. The Staatsoper will also present a six-part piano cycle featuring Daniel Barenboim, the young Chinese pianist Yuja Wang as well as András Schiff and Pierre-Laurent Aimard.

Two conductors who recently debuted with the Staatskapelle, Pietari Inkinen and Andris Nelsons, will return. Kirill Petrenko, another new-generation conductor, will lead the orchestra as a guest for the first time. Principal guest conductor Michael Gielen will conduct a symphony concert. Three song recitals with Anna Prohaska, Bejun Mehta and Ian Bostridge, in addition to a Baroque concert under the direction of Marc Minkowski, will further enrich the programme at the Schiller Theater. The chamber music series, successfully launched last season at the Rotes Rathaus (Berlin City Hall) and the Bode Museum, will be continued. The Werkstatt studio stage at the Schiller Theater, whose first season last year was enthusiastically received as a venue for innovative musical theater in Berlin, will present a John Cage cycle entitled Die Musik ist los – 100 Jahre Cage as part of the INFEKTION! festival, in addition to five premieres and one revival: Lucia Ronchetti’s Last Desire based on Oscar Wilde’s Salome, Manfred Stahnke’s Wahnsinn, das ist die Seele der Handlung based on texts by Edgar Allan Poe, Lehrstück by Paul Hindemith and Bertolt Brecht, and the Junge Staatsoper’s productions of Aschenputtel (Cinderella) by Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari and Moskau Tscherjomuschki, a musical comedy by Dmitri Shostakovich. Following more than 40 soldout performances, the opera Der gestiefelte Kater by César Cui is once again on the programme. The highly successful “Satie” evening Wissen Sie, wie man Töne reinigt? Satiesfactionen – with actors Jan Josef Liefers, Stefan Kurt and Klaus Schreiber – will also be revived.

And finally, the Staatsoper will return both this year and next year to the Bebelplatz. Against the backdrop of the opera building Unter den Linden, as impressive as ever despite reconstruction work, we are looking forward to celebrating STAATSOPER FÜR ALLE with many thousands of visitors - made possible by our partner BMW Berlin. On Sunday 26 June 2011 at 1:00 pm, Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin will perform an open-air concert. On 30 June 2012 the performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni with Anna Netrebko at the Schiller Theater will be shown live on wide screens on the Bebelplatz, followed on 1 July 2012 by a concert with Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin.

The complete 2011/2012 programme and all information is now online at: http://www.staatsoperberlin.de/.

Advance sales for all performances of the 2011/2012 season will begin on 14 May 2011.

Subscription sales start on 30 April 2011. FESTTAGE 2012 cycle tickets are on sale now.

Members of the Staatsoper Association (Förderverein), subscribers and StaatsopernCard holders enjoy advance purchase rights for all performances starting on 7 May 2011.

Tickets are available online at http://www.staatsoper-berlin.de/, by phone at 0049 30 20 35 45 55 and at the Staatsoper box office at the Schiller Theater.

Parsifal, Oper Leipzig, 22 April 2011

Leipzig Opera House

Parsifal – Stefan Vinke

Gurnemanz – James Moellenhoff

Klingsor – Jürgen Kurth

Kundry – Lioba Braun

Amfortas – Tuomas Pursio

Titurel – Roman Astakhov

First Knight of the Grail – Tommasso Randazzo

Second Knight of the Grial – Roman Astakhov

Esquires – Soula Parassidis, Jean Broekhuizen, Timothy Fallon, Norman Reinhardt

Alto solo – Claudia Huckle

Flowermaidens – Elena Tokar, Diana Schnürpel, Kathrin Göring, Soula Parassidis, Ines Reintzsch, Claudia Huckle

Roland Aeschlimann (director, designs)

Susanne Raschig (costumes)

Lucinda Childs (movement)

Ilka Weiss (assistance with designs and movement)

Lukas Kaltenbäck (lighting)

Chorus and Supplementary Chorus of the Leipzig Opera (chorus master: Volkmar Ulbrich)

Children’s Choir of the Leipzig Opera (Sophie Bauer)

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

Ulf Schirmer (conductor)

Parsifal on Good Friday, in the city of Wagner’s birth: how could one resist? I had enjoyed Roland Aeschlimann’s 2006 production, a Leipzig co-production with Geneva and Nice, when seeing it two years previously, and for the most part did so again, though there were perhaps some passages, especially during the third act, when its status as a repertory piece was now a little too evident. A little sharpening up of the stage direction would do no harm. This remains, however, an interesting and attractive production, which continues to remind me of Herbert Wernicke’s woefully underrated – at least by critics – Tristan for Covent Garden (not least when one recalls the reductionist Christof Loy staging that has succeeded it). Abstraction is not only the way to proceed in Wagner: the greatest current stage interpreter of his works, Stefan Herheim, is anything but abstract. Nevertheless, abstraction works well – especially when contrasted with the irrelevant pseudo-psychology that infects a good number of current Wagner productions.

Colour, as I wrote last time around, plays an important role, both in demarcating locations and in the dramatic transformations – an especially important concept in this of all Wagner’s dramas – that occur within particular scenes. That is the aspect which perhaps above all puts me in mind of the aforementioned Wernicke Tristan. I remain intrigued and equally uncertain about Aeschlimann’s Grail. Amfortas uncovers something mysterious – no problem there – and holds up a sheet which, by a trick of lighting presents what continues to remind me of a Turin Shroud-vision of Christ. I still wonder whether, even at this stage, we need something a little more substantial – in more than one sense – to offer sustenance for Monsalvat’s community Yet, by the same token, something else, again mysterious, is revealed, which clearly replenishes the community. The open-endedness of what is going on is very much in Wagner’s spirit of intellectual exploration and continual self-questioning. Visual centrality of the spear remains very much to the benefit of the second act, though I cannot help but regret the usual awkwardness at the end, when Parsifal refers to a sign (of the Cross) that he does not make. It need not be that particular Christian sign, of course, though it may be, but to have nothing at all simply does not seem to work very well.

Musically there was much to admire. The Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra sounded very much in its element, rich and dark of tone, especially in the strings. There were, especially during the first act, a few too many fluffs, not least during the Prelude, but once things had settled down, this ceased to be a problem. Much the same could be said of Ulf Schirmer’s direction. He may not come across as a great Wagnerian, but he is a dependably good one. Line is generally maintained, though parts of the third act dragged a little (not, I should stress, a matter of speed, but of dramatic momentum), though the Prelude to that act was world-weary indeed. Much of the cast was the same as I heard two years ago. Stefan Vinke’s Parsifal has gained a certain edge, or at least it had on the present occasion: there is still much to appreciate, but I hope the loss of freshness was temporary. James Moellenhoff’s Gurnemanz and Tuomas Pursio remain distinguished, though I sensed a certain lack of stage direction when contrasted with 2009. The major difference in the cast was Susan Maclean’s replacement by Lioba Braun, whom I had heard before as Kundry in Dresden, also in 2009. Then she was excellent, and so she was on this occasion, ever-attentive to the alchemic marriage of words and music, and notably more seductive – a matter of the production as much as anything else? – during the second act. Praise ought also to be offered to the excellent chorus, supplementary chorus, and children’s choir. Wagner’s interest in earlier music, not least as reflected in his early Das Liebesmahl der Apostel and his arrangement of Palestrina’s Stabat Mater, was evoked and translated into modern terms. Clarity and weight worked in tandem, to sometimes overwhelming effect.

Parsifal – Stefan Vinke

Gurnemanz – James Moellenhoff

Klingsor – Jürgen Kurth

Kundry – Lioba Braun

Amfortas – Tuomas Pursio

Titurel – Roman Astakhov

First Knight of the Grail – Tommasso Randazzo

Second Knight of the Grial – Roman Astakhov

Esquires – Soula Parassidis, Jean Broekhuizen, Timothy Fallon, Norman Reinhardt

Alto solo – Claudia Huckle

Flowermaidens – Elena Tokar, Diana Schnürpel, Kathrin Göring, Soula Parassidis, Ines Reintzsch, Claudia Huckle

Roland Aeschlimann (director, designs)

Susanne Raschig (costumes)

Lucinda Childs (movement)

Ilka Weiss (assistance with designs and movement)

Lukas Kaltenbäck (lighting)

Chorus and Supplementary Chorus of the Leipzig Opera (chorus master: Volkmar Ulbrich)

Children’s Choir of the Leipzig Opera (Sophie Bauer)

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

Ulf Schirmer (conductor)

|

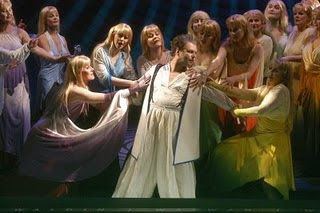

| Images: Andreas Birkigt Stefan Vinke (Parsifal) with the Flowermaidens |

Parsifal on Good Friday, in the city of Wagner’s birth: how could one resist? I had enjoyed Roland Aeschlimann’s 2006 production, a Leipzig co-production with Geneva and Nice, when seeing it two years previously, and for the most part did so again, though there were perhaps some passages, especially during the third act, when its status as a repertory piece was now a little too evident. A little sharpening up of the stage direction would do no harm. This remains, however, an interesting and attractive production, which continues to remind me of Herbert Wernicke’s woefully underrated – at least by critics – Tristan for Covent Garden (not least when one recalls the reductionist Christof Loy staging that has succeeded it). Abstraction is not only the way to proceed in Wagner: the greatest current stage interpreter of his works, Stefan Herheim, is anything but abstract. Nevertheless, abstraction works well – especially when contrasted with the irrelevant pseudo-psychology that infects a good number of current Wagner productions.

Colour, as I wrote last time around, plays an important role, both in demarcating locations and in the dramatic transformations – an especially important concept in this of all Wagner’s dramas – that occur within particular scenes. That is the aspect which perhaps above all puts me in mind of the aforementioned Wernicke Tristan. I remain intrigued and equally uncertain about Aeschlimann’s Grail. Amfortas uncovers something mysterious – no problem there – and holds up a sheet which, by a trick of lighting presents what continues to remind me of a Turin Shroud-vision of Christ. I still wonder whether, even at this stage, we need something a little more substantial – in more than one sense – to offer sustenance for Monsalvat’s community Yet, by the same token, something else, again mysterious, is revealed, which clearly replenishes the community. The open-endedness of what is going on is very much in Wagner’s spirit of intellectual exploration and continual self-questioning. Visual centrality of the spear remains very much to the benefit of the second act, though I cannot help but regret the usual awkwardness at the end, when Parsifal refers to a sign (of the Cross) that he does not make. It need not be that particular Christian sign, of course, though it may be, but to have nothing at all simply does not seem to work very well.

|

| End of Act II: Petra Lang is pictured here; on the present occasion, she was replaced by Lioba Braun |

Musically there was much to admire. The Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra sounded very much in its element, rich and dark of tone, especially in the strings. There were, especially during the first act, a few too many fluffs, not least during the Prelude, but once things had settled down, this ceased to be a problem. Much the same could be said of Ulf Schirmer’s direction. He may not come across as a great Wagnerian, but he is a dependably good one. Line is generally maintained, though parts of the third act dragged a little (not, I should stress, a matter of speed, but of dramatic momentum), though the Prelude to that act was world-weary indeed. Much of the cast was the same as I heard two years ago. Stefan Vinke’s Parsifal has gained a certain edge, or at least it had on the present occasion: there is still much to appreciate, but I hope the loss of freshness was temporary. James Moellenhoff’s Gurnemanz and Tuomas Pursio remain distinguished, though I sensed a certain lack of stage direction when contrasted with 2009. The major difference in the cast was Susan Maclean’s replacement by Lioba Braun, whom I had heard before as Kundry in Dresden, also in 2009. Then she was excellent, and so she was on this occasion, ever-attentive to the alchemic marriage of words and music, and notably more seductive – a matter of the production as much as anything else? – during the second act. Praise ought also to be offered to the excellent chorus, supplementary chorus, and children’s choir. Wagner’s interest in earlier music, not least as reflected in his early Das Liebesmahl der Apostel and his arrangement of Palestrina’s Stabat Mater, was evoked and translated into modern terms. Clarity and weight worked in tandem, to sometimes overwhelming effect.

Tuesday, 26 April 2011

Thomanerchor/Gewandhaus/Schwarz - St John Passion (1749 version), 21 April 2011

St Thomas's Church, Leipzig

Sibylla Rubens (soprano)

Marie-Claude Chappuis (contralto)

Johannes Chum (Evangelist and tenor arias)

Stephan Loges (Christ)

Hans-Christoph Begemann (bass arias)

Choir of St Thomas’s, Leipzig

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

Gotthold Schwarz (conductor)

The Thomanerchor’s Maundy Thursday and Good Friday Passion performances alternate annually between the St John and the St Matthew. This year, for a little variety, Bach’s 1749 (fourth) version of the former was presented. I do not recall hearing it before; there is little, however, about which to become excited, the most noteworthy changes being a matter of alterations to three aria texts. ‘Ich folge dir gleichfalls’ has some changes, arguably reflecting a less Baroque or Pietistic pictorial sensibility, likewise ‘Betrachte, meine Seel’. The text for ‘Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken’ is entirely replaced, the following words providing the new text:

An undeniable ‘rightness’ to the sound of boys’ voices was illustrated throughout. I do not mean to imply that mixed voices should not sing the work; I am happy to leave such fundamentalism to the ‘authenticke’ brigade, though commercial self-interest tends to render its practitioners oddly reluctant to employ what should surely be the ‘historically informed’ voices. Nevertheless, it is something very special to hear Bach’s own choir and – more or less – orchestra in his own church on Maundy Thursday, not least whilst beholding, as I did, Bach’s own countenance immediately opposite in one of St Thomas’s beautiful stained-glass windows – and that of Mendelssohn a little closer to the organ loft, in which the performances take place. It would, moreover, be ludicrous to claim that women’s voices sound the same as boys’, or indeed that a more mature chorus sounds as fresh as a youthful choir. Different choirs are possessed of different qualities. There was, moreover, no wanting of vigour in the turba choruses, Bach’s searing chromaticism proving as terrifying as anything in Tristan or Parsifal, the bloodlust if anything all the more chilling when expressed by young voices. ‘Sei gegrüßet, lieber Jüdenkönig!’ was, I am happy to report, taken at a relatively sedate tempo, allowing the words their full force. Bach’s writing, the Gospel itself, and the choral singing combined to impart an almost overwhelming sense of predestination as the performance progressed.

The question of soloists might be thought vexed, though only really if one adopts a fundamentalist approach: better to have professional soloists drawn from outside the choir than to have boys struggle, though it would be interesting on occasion to hear the soprano and alto arias taken by trebles. (Members of the choir did take smaller parts, such as the Maid and Peter.) Johannes Chum was an excellent Evangelist. Neither words nor music were unduly privileged; instead, one not only noted but experienced the miracle of Bach’s alchemic combination. Occasional strain with respect to the higher notes in his range was put to expressive use rather than jarring. Rainer Trost was listed in the programme booklet as the soloist for the tenor arias, but they were also sung by Chum. Though I should have been interested to hear the former, Chum proved an able replacement. It was not his fault, for instance, that a warmer, more Romantic string sound was not forthcoming in ‘Ach, mein Sinn’; nor, I am sure, was it the fault of the Gewandhaus Orchestra. The same could be said of the somewhat underpowered violin sound in ‘Mein Jesu, ach!’ Some ‘period’ practices die hard, alas. The entire continuo group proved distinguished throughout, however, not least David Petersen’s fruity bassoon.

Stephan Loges was a richly toned, expressive yet dignified Christ. Bach’s writing here lacks the celebrated string halo of Christ’s words in the St Matthew Passion, yet Loges ensured that one never felt the loss. Sibylla Rubens did not have a great deal to do as the soprano soloist. (What a contrast with the St Matthew!) Nevertheless, she proved radiantly beautiful in the pain of ‘Zerfließe, mein Herze’. Marie-Claude Chappuis was warmly expressive as contralto soloist. ‘Von deinen Stricken’ was more urgent than reflective, but that was doubtless Schwarz’s decision. Chappuis employed considerable ornamentation upon her da capo. Excellent cello and woodwind playing should also be noted. She navigated well the terrible contrasts of ‘Es ist vollbracht!’, aided by splendid solo gamba playing from Thomas Fritzsch. It seemed heartbreakingly apt that, by this hour, darkness had fallen in Leipzig too, Bach’s window image no longer visible. Hans-Christoph Begemann generally sounded more comfortable as Pilate than in the bass arias, where his tone tended towards the cloudy, in unfortunate contrast with Loges.

This was, however, not only an impressive but a moving performance. I can conceive of no better Holy Week observance.

Sibylla Rubens (soprano)

Marie-Claude Chappuis (contralto)

Johannes Chum (Evangelist and tenor arias)

Stephan Loges (Christ)

Hans-Christoph Begemann (bass arias)

Choir of St Thomas’s, Leipzig

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

Gotthold Schwarz (conductor)

The Thomanerchor’s Maundy Thursday and Good Friday Passion performances alternate annually between the St John and the St Matthew. This year, for a little variety, Bach’s 1749 (fourth) version of the former was presented. I do not recall hearing it before; there is little, however, about which to become excited, the most noteworthy changes being a matter of alterations to three aria texts. ‘Ich folge dir gleichfalls’ has some changes, arguably reflecting a less Baroque or Pietistic pictorial sensibility, likewise ‘Betrachte, meine Seel’. The text for ‘Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken’ is entirely replaced, the following words providing the new text:

Mein Jesu, ach! Dein schmerzhaft bitter LeidenGeorg Christoph Biller, the Thomaskantor, had been due to conduct; illness led to his replacement by Gotthold Schwarz. Schwarz’s approach was clearly ‘period’-informed, but not oppressively so, and was capable of variation. For instance, the great opening chorus was taking at a fast-ish though not absurd tempo; more importantly, the choir’s cries of ‘Herr’ pierced to the core against a properly turbulent backdrop as furnished by the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. I feared the worst when the ‘B’ section was terminated quite abruptly – always, to be fair, a difficult return to bring off convincingly – but other phrase- and section-endings were rounded off more naturally, for instance Christ’s recitative at the end of no.2. Likewise, chorales sounded unhurried – at least by today’s preposterous standards – and pauses were usually employed at ends of phrases. I was certainly impressed at the way Bach’s myriad of harmonic subtleties shone through – though one might well ask, how could it not? – in a chorale such as ‘Wer hat dich so geschlagen…?’ I did wonder, however, at the precedence of words over line in the penultimate line of ‘Christus, der uns selig macht’. Certainly the meaning of ‘verlacht, verhöhnt, und verspielt’ came across vividly, but the effect was arguably disruptive. The climactic chorus, ‘Ruht wohl,’ maintained its noble dignity, even if Schwarz’s imagination was somewhat less all-encompassing than that of a conductor such as Eugen Jochum (still my first choice for a recording).

bringt tausend Freuden,

es tilgt der Sünden Not.

Ich sehe zwar mit vielen Schrecken

den heiligen Leib mit Blute decken;

doch muss mir dies auch Lust erwecken,

es macht mich frei von Höll und Tod.

An undeniable ‘rightness’ to the sound of boys’ voices was illustrated throughout. I do not mean to imply that mixed voices should not sing the work; I am happy to leave such fundamentalism to the ‘authenticke’ brigade, though commercial self-interest tends to render its practitioners oddly reluctant to employ what should surely be the ‘historically informed’ voices. Nevertheless, it is something very special to hear Bach’s own choir and – more or less – orchestra in his own church on Maundy Thursday, not least whilst beholding, as I did, Bach’s own countenance immediately opposite in one of St Thomas’s beautiful stained-glass windows – and that of Mendelssohn a little closer to the organ loft, in which the performances take place. It would, moreover, be ludicrous to claim that women’s voices sound the same as boys’, or indeed that a more mature chorus sounds as fresh as a youthful choir. Different choirs are possessed of different qualities. There was, moreover, no wanting of vigour in the turba choruses, Bach’s searing chromaticism proving as terrifying as anything in Tristan or Parsifal, the bloodlust if anything all the more chilling when expressed by young voices. ‘Sei gegrüßet, lieber Jüdenkönig!’ was, I am happy to report, taken at a relatively sedate tempo, allowing the words their full force. Bach’s writing, the Gospel itself, and the choral singing combined to impart an almost overwhelming sense of predestination as the performance progressed.

The question of soloists might be thought vexed, though only really if one adopts a fundamentalist approach: better to have professional soloists drawn from outside the choir than to have boys struggle, though it would be interesting on occasion to hear the soprano and alto arias taken by trebles. (Members of the choir did take smaller parts, such as the Maid and Peter.) Johannes Chum was an excellent Evangelist. Neither words nor music were unduly privileged; instead, one not only noted but experienced the miracle of Bach’s alchemic combination. Occasional strain with respect to the higher notes in his range was put to expressive use rather than jarring. Rainer Trost was listed in the programme booklet as the soloist for the tenor arias, but they were also sung by Chum. Though I should have been interested to hear the former, Chum proved an able replacement. It was not his fault, for instance, that a warmer, more Romantic string sound was not forthcoming in ‘Ach, mein Sinn’; nor, I am sure, was it the fault of the Gewandhaus Orchestra. The same could be said of the somewhat underpowered violin sound in ‘Mein Jesu, ach!’ Some ‘period’ practices die hard, alas. The entire continuo group proved distinguished throughout, however, not least David Petersen’s fruity bassoon.

Stephan Loges was a richly toned, expressive yet dignified Christ. Bach’s writing here lacks the celebrated string halo of Christ’s words in the St Matthew Passion, yet Loges ensured that one never felt the loss. Sibylla Rubens did not have a great deal to do as the soprano soloist. (What a contrast with the St Matthew!) Nevertheless, she proved radiantly beautiful in the pain of ‘Zerfließe, mein Herze’. Marie-Claude Chappuis was warmly expressive as contralto soloist. ‘Von deinen Stricken’ was more urgent than reflective, but that was doubtless Schwarz’s decision. Chappuis employed considerable ornamentation upon her da capo. Excellent cello and woodwind playing should also be noted. She navigated well the terrible contrasts of ‘Es ist vollbracht!’, aided by splendid solo gamba playing from Thomas Fritzsch. It seemed heartbreakingly apt that, by this hour, darkness had fallen in Leipzig too, Bach’s window image no longer visible. Hans-Christoph Begemann generally sounded more comfortable as Pilate than in the bass arias, where his tone tended towards the cloudy, in unfortunate contrast with Loges.

This was, however, not only an impressive but a moving performance. I can conceive of no better Holy Week observance.

Friday, 22 April 2011

Die Walküre, Staatsoper Berlin, 17 April 2011

|

| Images: Monika Rittershaus Siegmund (Simon O'Neill) and Sieglinde (Anja Kampe) |

Siegmund – Simon O’Neill

Sieglinde – Anja Kampe

Hunding – Mikhail Petrenko

Wotan – René Pape

Brünnhilde – Iréne Theorin

Fricka – Ekaterina Gubanova

Gerhilde – Danielle Halbwachs

Ortlinde – Carola Höhn

Waltraute – Ivonne Fuchs

Schwertleite – Anaïk Morel

Helmwige – Erika Wueschner

Siegrune – Leann Sandel-Pantaleo

Grimgerde – Nicole Piccolomini

Rossweisse – Simone Schröder

Dancers – Guro Nagelhus Shia, Vebjorn Sundby

|

| Wotan (René Pape) |

|

| Wotan and Brünnhilde (Iréne Theorin) |

Guy Cassiers (director, set design)

Enrico Bagnoli (set design, lighting)

Tim van Steenbergen (costumes)

Arjen Klerkx, Kurt D’Haeseleer (video)

Michael P Steinberg, Detlef Giese (dramaturgy)

Csilla Lakatos (choreography)

Staatskapelle Berlin

Daniel Barenboim (conductor)

Guy Cassiers’s production of the Ring continues, in its second instalment, to baffle, but the nature of my bafflement is different from any other Ring I can recall. If ever there were a work overflowing with ideas – the overflowing and the conflict being part and parcel of the experience – it is surely the Ring. Yet the Belgian director, making his first foray into the opera house, seems to have none at all, let alone any sympathy with the strenuous intellectual and emotional demands presented by Wagner’s score. I was highly critical of the Weimar Ring, released on DVD, but at least it tried to present some conceptual framework, however confused. The concern of the present production, already staged at La Scala, seems to be to present a pleasant backdrop for what otherwise might as well be a concert performance. (Of course a staged performance never quite feels like that, since one tends to be more frustrated than one would in the concert hall, which possesses its own, symphonic virtues.) Lack is keenly felt here. The production is not ‘traditional’ in the sense of Otto Schenk’s mindless, ‘restorationist’ production for the Metropolitan Opera; it merely seems empty, devoid of meaning, whether political or otherwise. Quite what two dramaturges, Michael P Steinberg and Detlef Giese, did to earn their crust I cannot imagine. Taking the politics out is one thing, and the urge to be something other than a second-generation epigone of Joachim Herz or Patrice Chéreau is comprehensible, yet surely something then needs to be put in place of Wagner’s revolutionary socialism.

Take the Ride of the Valkyries. I recall Deryck Cooke’s wise retort to Eric Blom’s jibe about ‘the most tasteless piece of music ever written’: namely, ‘what could have been the use of a tasteful Ride of the Valkyries?’ This seems to be it, or at least to approach it: a scenic backdrop of elegant black horses, not entirely dissimilar from what one might find emblazoned on a Baroque fountain. That is it. At a push, one might speculate whether a point were being made concerning representational culture, a feudal order on the verge of being overthrow; however, there is no real suggestion of that being the case. A little later, we see ‘tasteful’ video projections of a male nude, credited as a dancer, almost Old Master-ish; I have no idea why. It seemed as though it were intended to do anything but épater les bourgeois. The Staatsoper has, after all, moved for the period of the Unter den Linden house’s closure, to the bürgerlich security of Charlottenburg’s Schillertheater, but a few hundred yards from the Deutsche Oper. Whereas Das Rheingold had at least provided novelty, if questionable, in the form of dancers on stage, their brief filmed sublimation here suggested running out of already limited steam. Video projections of René Pape’s (Wotan’s) face occasionally surfaced during the first act, when Wälse was mentioned; otherwise, it was difficult to note any other feature to the production. Red poles descend from the ceiling during the third act: they are not unpleasant to look at, yet do not seem to signify anything. Tim van Steenbergen’s costumes tend to be expensive-looking but unflattering, Brünnhilde’s taffeta-style bustle a case in point. Make of that, perhaps in West Berlin terms, what you will.

The performance proved considerably superior. Daniel Barenboim led a warmly Romantic account, starkly contrasting with the startling Neue Sachlichkeit objectivism he had imparted to Das Rheingold. I assume contrast between the frigid world of the gods and the purely human love of the Volsungs to have intended; that, at any rate, is how it came across, to the benefit of the present drama if not to that of the cycle’s Vorabend. It may be of interest to note that Barenboim has insisted upon a semi-covered pit for the Schillertheater, in partial imitation of Bayreuth. I am not sure what good this does; it is difficult to tell whether the somewhat restrained – or constrained – result is a product of the less than sensational acoustic of the Staatsoper’s temporary home or a matter of deliberate intent. What I can say is that Barenboim’s reading proved full of momentary incident whilst maintaining the necessary longer line, an especially difficult task in the second and third acts. This seemed to me the best conducted Walküre I had heard since Bernard Haitink’s account with the Royal Opera at the Royal Albert Hall; no one I have heard live has managed the melos of the second act of this drama quite so flawlessly as Haitink, but Barenboim was far from disgraced by the comparison. The Staatskapelle Berlin’s performance was not faultless – as it had arguably proved for the previous night’s Wozzeck, also conducted by Barenboim – but a number of errors were more than compensated for by the rich and variegated tone that emanated from the pit.

The cast was generally strong. Simon O’Neill’s Siegmund slightly disappointed, though O’Neill certainly did not lack power. His metallic timbre is not to my taste and his stage presence might best be described as old-fashioned gestural. (On the other hand, it was not clear that any of the singers received any assistance from the director.) Anja Kampe proved an increasingly spirited Sieglinde, improving in each act, her performance culminating in a radiant ‘O höchstes Wunder!’ Mikhail Petrenko maintained the high standards I noted from him as Hunding in Aix – and Hagen there in Götterdämmerung too. Most Hundings have been blacker of tone, yet Petrenko’s malevolent stage presence and delivery of text are ample substitute for the accustomed sound. Ekaterina Gubanova presented an imperious, wounded Fricka: the woman within and the stern moralising presence without were placed in finely judged counterpoint. The excellence of her Lyubasha in Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Tsar’s Bride, which had opened in London just three nights earlier (!), was admirably maintained. Iréne Theorin, Bayreuth’s current Isolde, overcame the handicap of her strange costume to portray a Brünnhilde gaining in humanity throughout her two acts, Wagner’s Feuerbachian conception of the ‘purely human’ being finely served. I have heard Valkyries more beautiful of tone, but Theorin presented no particular reason for complaint and displayed considerably more dramatic commitment than the production might have led one to expect.

René Pape’s Wotan, however, proved somewhat frustrating. He had sung Wotan in the Scala Rheingold but, already booked to sing Boris in New York, had ceded to the excellent Hanno Müller-Brachmann for Berlin. Müller-Brachmann’s Papageno-baritone was unlikely, however, to prove suitable for the Walküre Wotan, though perhaps the voice of a fabled Sarastro erred in the opposite direction, the tessitura sometimes sounding awkward. There is a tendency to sound wan in higher notes, though there is ample – too ample? – richness in the true bass register. I heard Pape a few years ago as Don Giovanni, again in Berlin under Barenboim. Then he merely seemed miscast; that was less apparent on this occasion, though doubts remained. That said, Pape’s beauty of tone certainly came very much to the fore at times; there was painful bitterness to be heard too. A more serious concern was apparent straying of his attention, most persistently during his ‘Farewell’ scene, in which a good number of words were the victims of substitution. I am told that there had been a greater number of errors during the final rehearsal. A great hope for the role, surely the summit for any pretender’s career, has yet, it seems, to fulfil the promise in which many of Pape’s admirers have long believed.

Under the terms of the co-production with La Scala, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung will be seen first in Berlin and subsequently in Milan. Those final two evenings will be staged during the Staatsoper’s 2012-13 season, culminating in complete cycles scheduled for Holy Week and Eastertide of the composer’s bicentenary.

Birtwistle and Dowland - 'Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben,' Montalvo/Klangforum Wien/Rundel, 18 April 2011

Werner-Otto-Saal, Konzerthaus Berlin

Birtwistle – Nine settings of Celan, for soprano and chamber ensemble

interspersed with:

Dowland – Lachrimae, arranged by Andreas Lindenbaum for violin, two violas, cello, and double bass

Marisol Montalvo (soprano)

Klangforum Wien

Peter Rundel (conductor)

Yes, you did read that correctly: ‘Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben,’ as in the final movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony. The Berlin Konzerthaus is organising something rather more interesting, indeed original, than many halls for the Mahler anniversary, a cycle of concerts in three parts of ‘Musik mit Mahler’. If the anniversary must be marked, then to use Mahler’s symphonies as a way of exploring other repertoire seems just the ticket.

Here resurrection took on a decidedly darker hue, with Birtwistle’s settings of Paul Celan, as translated by Michael Hamburger, scored for soprano, two clarinets, viola, cello, and double bass. Klangforum Wien gave the first performance of the complete work in 1996 and clearly has the music in its collective bones. The present performance was inspired and inspiring, not least on account of Peter Rundel’s intelligent direction. Marisol Montalvo made a generally good impression as soprano, though sometimes her American accent sounded a little out of place – at least to an Englishman. At the heart of Birtwistle’s music is a melancholy that Montalvo’s more showy delivery did not always quite capture, though the final sound of her unaccompanied voice, deserted by instruments, was chilling, likewise the iridescence of her voice in combination with instruments during ‘Mit Brief und Uhr’ . Clarinets are a typical vessel of Birtwistle’s expression, here (Reinhold Brunner and Bernhard Zachhuber) harking back on occasion to the hieratic timelessness of Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments as well as to the violence of Birtwistle’s own Punch and Judy, later arabesques ably echoed by soprano, and vice versa. ‘Tenebrae’ seemed to acquire further meaning when heard at the beginning of Holy Week – even when, perhaps particularly when, performed in one of the most atheistic cities in the world.

Every bit as inspired was the decision to perform the Celan settings interspersed with John Dowland’s Lachrymae, here arranged for strings by cellist Andreas Lindenbaum, on hand to perform, alongside Gunde Jäck-Micko on violin, violists Andrew Jezek and Dimitrios Polisoidis, and double bassist Uli Fussenegger. Vibrato was avoided, though I thought I heard a little more as time went on. Perhaps it was; perhaps my ears had adjusted. The motivation in recreating the world of the viol consort was clear, though I could not help but wish for a little more variation in tone quality on occasion. That said, the excellent players afforded ample opportunity to luxuriate in the plangent melancholy of Dowland’s harmonies. This was not quite Haydn’s Seven Last Words: for one thing, there is greater variety of tempo. However, the effect was not entirely dissimilar, suggesting another possible companion piece for Birtwistle’s settings. Dowland, however, remains closer in spirit to his great English successor than Haydn will ever be, with Purcell’s Fantazias another ghost at the feast.

Birtwistle – Nine settings of Celan, for soprano and chamber ensemble

interspersed with:

Dowland – Lachrimae, arranged by Andreas Lindenbaum for violin, two violas, cello, and double bass

Marisol Montalvo (soprano)

Klangforum Wien

Peter Rundel (conductor)

Yes, you did read that correctly: ‘Sterben werd’ ich, um zu leben,’ as in the final movement of Mahler’s Second Symphony. The Berlin Konzerthaus is organising something rather more interesting, indeed original, than many halls for the Mahler anniversary, a cycle of concerts in three parts of ‘Musik mit Mahler’. If the anniversary must be marked, then to use Mahler’s symphonies as a way of exploring other repertoire seems just the ticket.

Here resurrection took on a decidedly darker hue, with Birtwistle’s settings of Paul Celan, as translated by Michael Hamburger, scored for soprano, two clarinets, viola, cello, and double bass. Klangforum Wien gave the first performance of the complete work in 1996 and clearly has the music in its collective bones. The present performance was inspired and inspiring, not least on account of Peter Rundel’s intelligent direction. Marisol Montalvo made a generally good impression as soprano, though sometimes her American accent sounded a little out of place – at least to an Englishman. At the heart of Birtwistle’s music is a melancholy that Montalvo’s more showy delivery did not always quite capture, though the final sound of her unaccompanied voice, deserted by instruments, was chilling, likewise the iridescence of her voice in combination with instruments during ‘Mit Brief und Uhr’ . Clarinets are a typical vessel of Birtwistle’s expression, here (Reinhold Brunner and Bernhard Zachhuber) harking back on occasion to the hieratic timelessness of Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments as well as to the violence of Birtwistle’s own Punch and Judy, later arabesques ably echoed by soprano, and vice versa. ‘Tenebrae’ seemed to acquire further meaning when heard at the beginning of Holy Week – even when, perhaps particularly when, performed in one of the most atheistic cities in the world.

Every bit as inspired was the decision to perform the Celan settings interspersed with John Dowland’s Lachrymae, here arranged for strings by cellist Andreas Lindenbaum, on hand to perform, alongside Gunde Jäck-Micko on violin, violists Andrew Jezek and Dimitrios Polisoidis, and double bassist Uli Fussenegger. Vibrato was avoided, though I thought I heard a little more as time went on. Perhaps it was; perhaps my ears had adjusted. The motivation in recreating the world of the viol consort was clear, though I could not help but wish for a little more variation in tone quality on occasion. That said, the excellent players afforded ample opportunity to luxuriate in the plangent melancholy of Dowland’s harmonies. This was not quite Haydn’s Seven Last Words: for one thing, there is greater variety of tempo. However, the effect was not entirely dissimilar, suggesting another possible companion piece for Birtwistle’s settings. Dowland, however, remains closer in spirit to his great English successor than Haydn will ever be, with Purcell’s Fantazias another ghost at the feast.

Thursday, 21 April 2011

Wozzeck, Staatsoper Berlin, 16 April 2011

Schillertheater

Wozzeck – Roman Trekel

Drum Major – John Daszak

Andres – Florian Hoffmann

Captain – Graham Clark

Doctor – Pavlo Hunka

Marie – Nadja Michael

Margret – Katharina Kammerloher

First Apprentice – Jürgen Linn

Second Apprentice – James Homann

Idiot – Heinz Zednik

Marie’s Child – Fabian Sturm

Andrea Breth (director)

Martin Zehetgruber (stage designs)

Silke Willrett, Marc Weeger (costumes)

Olaf Freese (lighting)

Jens Schroth (dramaturgy)

Staatskapelle Berlin

Staatsopernchor Berlin (chorus master: Eberhard Friedrich)

Children’s Choir of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden

Daniel Barenboim (conductor)

Though it was the first opera I saw in the theatre – bar a reduced Don Giovanni – it had been quite a while since I had seen a staged performance of Wozzeck, most likely the greatest of all twentieth-century operas. Certainly its stature seems somehow to grow with every hearing. Keith Warner’s Covent Garden production had its detractors, but I thought it in many respects impressive. Andrea Breth, in her first production for the Berlin State Opera, presented a more ‘faithful’ reading, but fidelity should not be confused in this instance with lack of commitment. It was indeed in the cases where she presented a different interpretation from that suggested in libretto and score that the production seemed weaker. In what came across – even if it were not intended this way – as a strangely misogynistic reading, Marie’s inner conflict was minimised: she did not appear to struggle at all with her conscience in the context of the Drum-Major’s advances, and indeed submitted a few inches away from her son, in full view of him. (I did wonder, without being prudish, whether this was really something appropriate for a child to witness, though I have no reason to think that Fabian Sturm’s fear was not acted.) Moreover, not having Marie read from the Bible, but simply recall it from memory, eliminated an important point that she has struggled to attain literacy. Margret, meanwhile, seemed merely a tart, and a paralytic one at that. The other odd decision was to have Wozzeck, presumably dead, tell his son that his mother was dead; no other children were on stage, their rhyme being delivered from the pit. Presumably a point about the cyclical nature of the tragedy was being made, but the chilling nature of children’s callous insouciance was lost.

Otherwise, the oppressive nature of an inhuman society was portrayed starkly. There could be no doubt that the singers had been properly directed, a welcome contrast with the previous night’s Salome at the Komische Oper. Actions and scene changes were well choreographed throughout in a thoroughly professional display. Martin Zehetgruber’s dark stage designs were simple, unfussy, and always apt. Militarism was present, as it should be, but never overplayed. The form it takes is, after all, a product of capitalist society, not its cause. The same could and should be said of the Doctor’s nasty experiments and his lust for bourgeois renown. As for the miserable depravity of proletarian life, whether in the barracks or for Marie, ‘wir arme Leut’ indeed… But never were such broader themes, undoubtedly present in the work itself, trumpeted over and above it: this was Berg’s Wozzeck, not, with the exceptions outlined above, Andrea Breth’s.

Daniel Barenboim was on excellent form in the pit, likewise the Staatskapelle Berlin. I might have expected a more overtly ‘Wagnerian’ reading, but then Barenboim’s Wagner has always been more variegated than many seem to think, and his Berg followed suit. There were power and punch when required, which of course includes the wrenching D minor climax of the final Interlude: tonality aufgehoben in a way Schoenberg may sometimes have attempted but never quite accomplished. (Webern never tried.) Not once was there any doubt as to Barenboim’s command of line, but equally impressive were an ear for colour surely born of his experience in French music, not least Debussy, and his characterisation of the closed forms and genres of which the greater structure is composed.

Roman Trekel’s was one of the best performances I have heard him give, a great improvement upon his disappointing Eugene Onegin, on a par with his fine Doktor Faust. The dryness that has sometimes affected his voice was not at all in evidence on the present occasion. His was not an overtly emotional Wozzeck, not perhaps as searching nor as terrifying as Matthias Goerne’s, but Trekel’s Lieder-singer attention to detail paid dividends nevertheless. Nadja Michael gave her all as Marie. At her best, she is a fine singing actress; here, her vocal power proved generally as impressive as her stage presence. It would have been good to have had more of the right notes, but she is far from the only singer in this role to stand guilty in that respect. The Captain is a role made for a Mime such as Graham Clark; he did not disappoint, nor did Pavlo Hunka in the dangerous, deranged role of the Doctor. John Daszak, replete with plastic muscles, made a virile thug indeed of the Drum-Major, though never at the expense of musical values. Florian Hoffmann proved fair of voice indeed as Andres, as well as convincing on stage: this is clearly a young singer to watch. And finally, it was a genuinely moving pleasure to welcome back Heinz Zednik to the stage in a typically finely observed performance as the Idiot. But the whole was so much more than the sum of the parts: a description of performance as well as work.

Lulu will follow during next year’s Festtage, again conducted by Barenboim and directed by Breth. Barenboim said at a press conference a couple of days later that he hopes to conduct both works over a number of weekends, to allow visitors to experience a Berlin ‘Berg Weekend’, a mouth-watering prospect indeed.

|

| Captain (Graham Clark) and Wozzeck (Roman Trekel) Images: Bernd Uhlig |

Wozzeck – Roman Trekel

Drum Major – John Daszak

Andres – Florian Hoffmann

Captain – Graham Clark

Doctor – Pavlo Hunka

Marie – Nadja Michael

Margret – Katharina Kammerloher

First Apprentice – Jürgen Linn

Second Apprentice – James Homann

Idiot – Heinz Zednik

Marie’s Child – Fabian Sturm

Andrea Breth (director)

Martin Zehetgruber (stage designs)

Silke Willrett, Marc Weeger (costumes)

Olaf Freese (lighting)

Jens Schroth (dramaturgy)

Staatskapelle Berlin

Staatsopernchor Berlin (chorus master: Eberhard Friedrich)

Children’s Choir of the Staatsoper Unter den Linden

Daniel Barenboim (conductor)

|

| Marie (Nadja Michael) with her child (Fabian Sturm) |

|

| Wozzeck and the Doctor (Pavlo Hunka) |

|

| Andres (Florian Hoffmann) and Wozzeck |

Otherwise, the oppressive nature of an inhuman society was portrayed starkly. There could be no doubt that the singers had been properly directed, a welcome contrast with the previous night’s Salome at the Komische Oper. Actions and scene changes were well choreographed throughout in a thoroughly professional display. Martin Zehetgruber’s dark stage designs were simple, unfussy, and always apt. Militarism was present, as it should be, but never overplayed. The form it takes is, after all, a product of capitalist society, not its cause. The same could and should be said of the Doctor’s nasty experiments and his lust for bourgeois renown. As for the miserable depravity of proletarian life, whether in the barracks or for Marie, ‘wir arme Leut’ indeed… But never were such broader themes, undoubtedly present in the work itself, trumpeted over and above it: this was Berg’s Wozzeck, not, with the exceptions outlined above, Andrea Breth’s.

|

| In the barracks |

Daniel Barenboim was on excellent form in the pit, likewise the Staatskapelle Berlin. I might have expected a more overtly ‘Wagnerian’ reading, but then Barenboim’s Wagner has always been more variegated than many seem to think, and his Berg followed suit. There were power and punch when required, which of course includes the wrenching D minor climax of the final Interlude: tonality aufgehoben in a way Schoenberg may sometimes have attempted but never quite accomplished. (Webern never tried.) Not once was there any doubt as to Barenboim’s command of line, but equally impressive were an ear for colour surely born of his experience in French music, not least Debussy, and his characterisation of the closed forms and genres of which the greater structure is composed.

|

| Tavern scene |

Roman Trekel’s was one of the best performances I have heard him give, a great improvement upon his disappointing Eugene Onegin, on a par with his fine Doktor Faust. The dryness that has sometimes affected his voice was not at all in evidence on the present occasion. His was not an overtly emotional Wozzeck, not perhaps as searching nor as terrifying as Matthias Goerne’s, but Trekel’s Lieder-singer attention to detail paid dividends nevertheless. Nadja Michael gave her all as Marie. At her best, she is a fine singing actress; here, her vocal power proved generally as impressive as her stage presence. It would have been good to have had more of the right notes, but she is far from the only singer in this role to stand guilty in that respect. The Captain is a role made for a Mime such as Graham Clark; he did not disappoint, nor did Pavlo Hunka in the dangerous, deranged role of the Doctor. John Daszak, replete with plastic muscles, made a virile thug indeed of the Drum-Major, though never at the expense of musical values. Florian Hoffmann proved fair of voice indeed as Andres, as well as convincing on stage: this is clearly a young singer to watch. And finally, it was a genuinely moving pleasure to welcome back Heinz Zednik to the stage in a typically finely observed performance as the Idiot. But the whole was so much more than the sum of the parts: a description of performance as well as work.

|

| Final scene |

Lulu will follow during next year’s Festtage, again conducted by Barenboim and directed by Breth. Barenboim said at a press conference a couple of days later that he hopes to conduct both works over a number of weekends, to allow visitors to experience a Berlin ‘Berg Weekend’, a mouth-watering prospect indeed.

Salome, Komische Oper, 15 April 2011

Komische Oper, Berlin

Salome – Morenike Fadayomi

Herodias – Christiane Oertel

Page to Herodias – Karolina Gumos

Herod – Andreas Conrad

Narraboth – Thomas Ebenstein

Jokanaan – Egils Silins

First Nazarene – Jan Martinik

Second Nazarene – Raphael Bütow

First Soldier – Hans-Peter Scheidegger

Second Soldier – Adam Cioffari

First Jew – Christoph Schröter

Second Jew – Peter Renz

Third Jew – Matthias Siddhartha Otto

Fourth Jew – Thomas Ebenstein

Fifth Jew – Marko Spehar

A Cappadocian – Ipca Ramanovic

A Slave – Sven Goiny

Thilo Reinhardt (director)

Paul Zoller (set designs)

Katharina Gault (costumes)

Ingo Gerlach (dramaturgy)

Franck Evin (lighting)

Orchestra of the Komische Oper, Berlin

Alexander Vedernikov (conductor)

Confusion reigned in the ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’, the idea apparently being to substitute Herod’s weird and wonderful fantasies, though can anyone actually think of quite so many things during that time? John the Baptist and, I think, Jesus competed for attention, perhaps leaders of rival cults. Was one a false prophet or both? Who was who? And with whom would Salome throw in her lot? The cars and phalluses were too silly to be offensive, though one could imagine some finding it all blasphemous. A veiled woman suggested something more daring, but she did nothing more than stand there; clearly Christian sensibilities are fairer game than certain others. So far, so fantastical; perhaps it was revealing to some. However, confusion reigned throughout Thilo Reinhardt’s production, suggesting that the former chaos might have been more by default than a product of intention. Salome was reduced to cartoon status, replete with captions, and not only in terms of Paul Zoller’s garish designs. There seemed on one level to be plenty of ideas, or at least thoughts, but they never cohered into any particular idea, let alone Konzept; nor even did there appear to be any effort made to make them cohere.