Nationaltheater, Munich

|

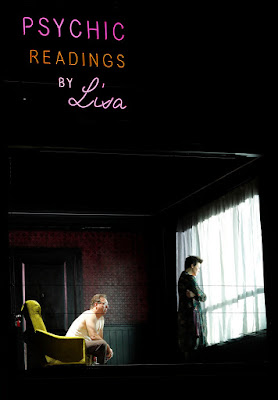

| Gutrune (Anna Gabler, Brünnhilde (Nina Stemme) Images: © Wilfried Hösl |

Siegfried – Stefan Vinke

Gunther – Markus Eiche

Hagen – Hans-Peter König

Alberich – John Lundgren

Brünnhilde – Nina Stemme

Gutrune, Third Norn – Anna

Gabler

Waltraute, First Norn – Okka

von der Damerau

Woglinde – Hanna-Elisabeth

Müller

Wellgunde – Rachael Wilson

Flosshilde, Second Norn –

Jennifer Johnston

Andreas Kriegenburg (director)

Georgine Balk (revival

director)

Harald B. Thor (set designs)

Andrea Schraad (costumes)

Stefan Bolliger (lighting)

Zenta Haerter (choreography)

Marton Tiedtke, Olaf A. Schmitt

(dramaturgy)

Bavarian State Opera Chorus and

Extra Chorus (chorus master: Sören Eckhoff)

Bavarian State Orchestra

Kirill Petrenko (conductor)

What I am about to write must

be taken with the proviso that I have not seen, this year or any other, the

rest of Andreas Kriegenburg’s Munich Ring.

Friends tell me that would have made little difference, yet I cannot know for

certain. It is also an odd thing, perhaps, to start as well as to end with Götterdämmerung, although that oddness

may well be overstated. Wagner’s initial intention was, after all, to write a

single drama on the death of Siegfried; after a certain point in the formulation

of the Ring project, much of what had

been written as Siegfrieds Tod

remained as Götterdämmerung. Might

one even be able to recapture something of that initial intent, relying on the

narrations here as they might originally have been conceived? Perhaps – and it

is surely no more absurd intrinsically to watch – and to listen to – one of the

Ring dramas than it is to one part of

the Oresteia. On the other hand, a Götterdämmerung conceived as a one-off –

whether in simple terms or as part of a series such as that presented some time

ago by Stuttgart, each by a different director, glorying in rather than

apologising for disjuncture and incoherence – will perhaps be a different thing

from this. Anyway, we have what we have, and I can only speak of what I have

seen and heard.

|

In that respect, I am afraid,

this Götterdämmerung proved sorely

disappointing – especially, although not only, as staging. Indeed, the apparent

vacuity of the staging combined with what seemed a distinctly repertoire

approach – yes, I know there will always be constraints upon what a theatre can

manage – combined to leave me resolutely unmoved throughout. This did not seem

in any sense to be some sort of post-Brechtian strategy, a parallel to where

parts at least of Frank

Castorf’s now legendary Bayreuth Ring

started out – if not, necessarily, always to where they ended up. I distinctly

had the impression that what acting we saw had come from a largely excellent

cast. Is that at least an implicit criticism of the revival direction? Not

necessarily. I know nothing of how what few rehearsals I suspect there were had

been organised. I could not help but think, though, that once again Wagner’s wholesale

rejection – theoretical and, crucially, practical too – of the ideology and

practices of ‘normal’ theatres had once again been vindicated. This, after all,

is the final day of a Bühnenfestspiel.

At one point, he even wrote of post-revolutionary performances in a temporary

theatre on the banks of the Rhine, after which it and the score would be burnt.

Did he mean that? At the time, he probably did, just as we mean all sorts of

things at the time we might not actually do in practice. Nevertheless, his

rejection of everyday practice points us to an important truth concerning his

works. As Pierre Boulez, whilst at work on the Ring at Bayreuth, put it: ‘Opera houses are often rather like cafés

where, if you sit near enough to the counter, you can hear waiters calling out

their orders: “One Carmen! And one Walküre! And one Rigoletto!”’ What was needed, Boulez noted approvingly, ‘was an

entirely new musical and theatrical structure, and it was this that he [Wagner]

gradually created’. Bayreuth, quite rightly, remains the model; Bayreuth, quite

wrongly, remains ignored by the rest of the world.

Such unhelpfulness out of the

way, what did we have? Details of Kriegenburg’s staging seem to borrow heavily –

let us say, pay homage to – from other productions. The multi-level,

modern-office-look set is not entirely unlike that for Jürgen Flimm’s (justly

forgotten) Bayreuth staging. Brünnhilde arrives at the Gibichung Court with a

paper bag over her head, although it is sooner shed than in Richard Jones’s old

Covent Garden Ring. I shall not list

them all, but they come across here, without much in the way of conceptual

apparatus, more as clichés than anything else. Are they ironised, then? Not so

far as I could tell. I liked Siegfried’s

making his way through a baffling – to him – crowd of consumers, as he entered

into the ‘real world’, images from advertising and all. Alas, the idea did not

really seem to lead anywhere.

A euro figure (€) is present; perhaps it has been before. First, somewhat bafflingly, it is there as a rocking horse for Gutrune; again, perhaps there is a backstory to that. Then, it seems to do service – not a bad idea, this – as an unclosed ring-like arena for some of the action, although it is not quite clear to me why it does at some times and not at others. Presumably this is the euro as money rather than as emblematic hate-figure for the ‘euroscepticism’ bedevilling Europe in general and my benighted country in particular. (That said, I once had the misfortune to be seated in front of Michael Gove and ‘advisor’, whose job appeared to be to hold Gove’s jacket, at Bayreuth; so who knows?) There also seems to be a sense of Gutrune as particular victim, an intriguing sense, although again it is only intermittently maintained. Doubtless her behaviour earlier on, drunk, hungover, posing for selfies with the vassals, might be ascribed to her exploitation by the male society; here, however, it comes perilously close to being repeated on stage rather than criticised. That she is left on stage at the end, encircled by a group of actors who occasionally come on to ‘represent’ things – the Rhine during Siegfried’s journey, for instance – is clearly supposed to be significant. I could come up with various suggestions why that might be so; I am not at all convinced, however, that any of them would have anything to do with the somewhat confused and confusing action here.

A euro figure (€) is present; perhaps it has been before. First, somewhat bafflingly, it is there as a rocking horse for Gutrune; again, perhaps there is a backstory to that. Then, it seems to do service – not a bad idea, this – as an unclosed ring-like arena for some of the action, although it is not quite clear to me why it does at some times and not at others. Presumably this is the euro as money rather than as emblematic hate-figure for the ‘euroscepticism’ bedevilling Europe in general and my benighted country in particular. (That said, I once had the misfortune to be seated in front of Michael Gove and ‘advisor’, whose job appeared to be to hold Gove’s jacket, at Bayreuth; so who knows?) There also seems to be a sense of Gutrune as particular victim, an intriguing sense, although again it is only intermittently maintained. Doubtless her behaviour earlier on, drunk, hungover, posing for selfies with the vassals, might be ascribed to her exploitation by the male society; here, however, it comes perilously close to being repeated on stage rather than criticised. That she is left on stage at the end, encircled by a group of actors who occasionally come on to ‘represent’ things – the Rhine during Siegfried’s journey, for instance – is clearly supposed to be significant. I could come up with various suggestions why that might be so; I am not at all convinced, however, that any of them would have anything to do with the somewhat confused and confusing action here.

|

| Siegfried (Stefan Vinke), Hagen (Hans-Peter König), Gutrune |

Kirill Petrenko led a far from negligible account of the score, which, a

few too many orchestral fluffs aside – it nearly always happens in Götterdämmerung, for perfectly obvious

reasons – proved alert to the Wagnerian melos. It certainly marked an advance

upon the often hesitant work I heard from him in the Ring at Bayreuth. However, ultimately, it often seemed – to me – observed

rather than participatory, especially during the Prologue and First Act. The emotional

and intellectual involvement I so admired in, for instance, his performances of

Tannhäuser and Die Meistersinger here in Munich was not so evident. Perhaps some at

least of that dissatisfaction, however, was a matter of the production failing

to involve one emotionally at all. The Munich audience certainly seemed more

appreciative than I, so perhaps I was just not in the right frame of mind.

|

| Waltraute (Okka von der Damerau), Brünnhilde |

Much the same might be said of the singing. Nina Stemme’s Brünnhilde

redeemed itself – as well, perhaps, as the world – in the third act, recovering

some of that sovereign command we know, admire, even love,

although even here I could not help but reflect how surer her performance at

the 2013

Proms under Daniel Barenboim had been. There is nothing wrong with using

the prompter; that is what (s)he is there for, as Strauss’s Capriccio M. Taupe might remind us.

Stemme’s – and not only Stemme’s – persistent resort thereto, however,

especially when words were still sometimes confused, was far from ideal during

the first and second acts. Stefan Vinke ploughed through the role of Siegfried,

often heroically, sometimes with a little too grit in the voice, yet with

nothing too much to worry about. It was not a subtle portrayal, but then, what

would a subtle Siegfried be?

|

| Hagen and Gunther (Markus Eiche) |

Some might have found Hans-Peter König a little too kindly of voice as

Hagen; I rather liked the somewhat avuncular persona, with a hint of

concealment. Again, there was no doubting his ability to sing the role. Markus

Eiche and Anna Gabler were occasionally a little small of voice and, in Eiche’s

case, presence as his half-siblings, but there remained much to admire: Gabler’s

whole-hearted embrace of that reimagined role, for one thing. Okka von der Damerau made for a wonderfully

committed, concerned Waltraute: as so often, the highlight of the first act. John

Lundgren’s darkly insidious Alberich left one wanting more, much more. The

Rhinemaidens and Norns were, without exception, excellent. I especially loved

the contrasting colours – Jennifer Johnson’s contralto-like mezzo in particular

– and blend from the latter in the opening

scene. If there are downsides to repertory systems, casting from depth as here

can prove a distinct advantage. Choral singing was of the highest standard too.

|

| Brünnhilde, Gunther, and the vassals |

If only the production, insofar

as I could tell, had had more to say and more to bring these disparate elements

together. Without the modern look, it might often as well have been Robert Lepage or Otto Schenk.