|

| Images: Clive Barda / ROH |

Hermann, Landgrave of Thuringia – Mika Kares

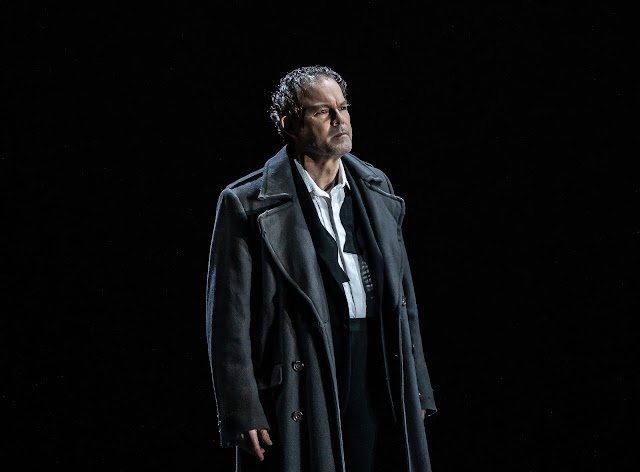

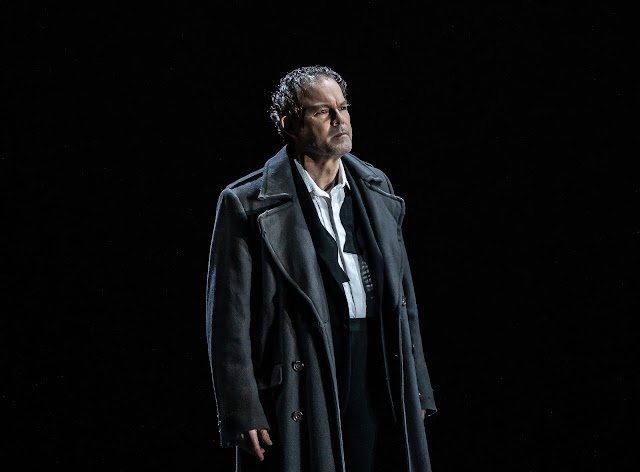

Tannhäuser – Stefan Vinke

Wolfram von Eschenbach – Gerald Finley

Walther von der Vogelweide – Egor Zhuravskii

Biterolf – Michael Kraus

Heinrich der Schreiber – Michael Gibson

Reinmar von Zweter – Jeremy White

Elisabeth – Lise Davidsen

Venus – Ekaterina Gubanova

Young Shepherd – Sarah Dufresne

Elisabeth’s Attendants – Kathy Bathko, Deborah Peake-Jones, Louise Armit, Amanda Baldwin

Dancers – Matthew Cotton, Camilla Curiel, Donny Ferris, Evelyn Hart, Liudmila Loglisci, Risa Maki, Sean Moss, Andrea Paniagua, George Perez, Thomas Kerek, Hobie Schouppe, Juliette Tellier

Tim Albery (director)

Jasmin Vardimon (choreography, Venusberg scene)

Michael Levine (set designs)

Jon Morrell (costumes)

David Finn (lighting)

Maxine Braham (movement)

Royal Opera Chorus (chorus director: William Spaulding)

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

Sebastian Weigle (conductor)

‘R. slept well and has decided to have a massage only once a day,’ writes Cosima Wagner in one of her last diary entries, from Venice, only twenty days before Richard’s death (when Cosima’s world and thus her diary came to an end). The day took its course, via Cosima’s characteristic desire ‘not to thwart or overburden the cherished workings of his mind,’ a ride to the Piazzetta during which Wagner extols Bach’s fugues, luncheon, visitors, R. yet again reading Gobineau, to: ‘Chat in the evening, brought to an end by R. with the “Shepherd’s Song” and “Pilgrim’s Chorus” from

Tannhäuser. He says he still owes the world a

Tannhäuser.’

With those celebrated words—and the tantalising prospect of hearing Wagner, even at that stage in his life, playing from his

Grosse romantische Oper at the piano, perhaps singing along—the composer pointed not only to ongoing dissatisfaction with the form

Tannhäuser, revisions notwithstanding, had yet reached. He also drew attention to the potential he believed his material, musical and dramatic, still had to reach a more satisfactory, perhaps more ‘finished’ state. Should one agree with Wagner—a sizable contingent has long preferred to shun changes made for Paris and Vienna, adhering to something close to what was originally given in Dresden—these twin, related issues will inevitably inform musical performance and staging alike. (Arguably, even if one returns to Dresden, less easy than some claim, one cannot forget what comes after, and that will continue to colour in one way or another the approach one takes. ‘Authenticity’ is always an illusion and usually a pernicious one.) Whether problem, opportunity, or both, it was difficult not to sense such questions hanging over what was seen and heard in the second revival of Tim Albery’s production for Covent Garden, now conducted by Sebastian Weigle.

It is certainly difficult to imagine a

Tannhäuser in which the dichotomy between Venusberg and Wartburg does not loom large—some might say damagingly so, crushing the prospects for more plausible psychological motivation. (Some, equally might say this is Wagnerian myth, not Ibsen; psychological realism is hardly at issue here, at least not straightforwardly so.) Take the opening Venusberg scene, where the greatest difference between ‘Dresden’ and ‘Paris’—whatever qualifications we can and should add, still the fundamental distinction between versions—will always be seen and heard. It is rare,

though not quite unheard of, in my experience not to regret the loss of the additional music written for Paris, should director and/or conductor opt for Dresden. In many ways, the Overture and Bacchanale were promising. Weigle’s way with the former, in particular, seemed to look (listen) back, a more Mendelssohnian Wagner than one often hears, with what at times sounded like—though surely were not—more chamber orchestral forces. What, surely, one then should hear is an invasion from the realm of Tristan; one—or I—never quite did. The stylistic incongruity of later material, such as it is, should be enabled to present immanent critique. Here, I am afraid, it simply seemed to go on for a bit too long: surely missing one of several points. It was, to a certain extent, made up for by the excellence of the dancers, strangely choreographed by Jasmin Vardimon, in a way that more often suggests school PE lessons than something more conventionally erotic. (Maybe that is the point, but it is probably better not to go there.) The dancing itself, though, deserves credit as first-rate; without that, it would have been a long trudge, and without the excuse of being a pilgrimage.

Albery’s production itself has its moment of greatest promise here—probably not coincidentally. The opera house, however many times we have seen this before, is fruitfully reflected onstage. Whether Tannhäuser has made it as artist and stands in need of a fresh, perhaps less sticky, challenge, or whether he was mad to leave is left to us, which is fair enough. But the conflation of Venusberg, Royal Opera House, and, in couplings with dancers, the Paris Jockey Club too has something to be said for it—if only its implications had been pursued. For, apart from when it necessarily returns close to the end, the idea of Tannhäuser as artist seems pretty much to be dropped. The proscenium arch lies as a ruin in the second act, but why we are in what seems to be a guerrilla war zone—Bosnia, we originally thought, perhaps now Ukraine—I have no idea. I cannot imagine the idea is that, without Covent Garden, love it as we may, there will be civil war, but who knows? No one I have spoken to, at any rate. Much of what unfolded seemed barely directed at all, as if the singers had been left to fend for themselves; perhaps they had.

Weigle proved more variable. The first act increasingly dragged. I do not know how long it actually lasted on the clock, but it seemed to last longer than any I could recall. Part of that, doubtless, was the production, but there was a near-fatal lack of inner, musical tension, recovered, albeit fitfully, during the second and third acts. What was ultimately lacking, though, was any real sense of the musical architecture. This can, arguably should, be understood in various ways. It need not all be Klemperer (though what I should give to hear that putative performance), nor for that matter Furtwängler (likewise). Likewise, it need not all be Wagner’s various musical inheritances, grand opéra included, just as it need not all be aspiration towards music-drama proper. But some sense of being more than number opera joined up is surely essential, or at the very least strongly desirable. The orchestra, likewise, came and went, strings sometimes sounding scrawny, at others blooming nicely. Offstage brass, however, was magnificent. There were many pleasures to be heard from vernal woodwind too.

Another, more prosaic, type of problem was presented by Stefan Vinke in the title role. Four nights previously, on the first night, he had withdrawn through illness. This time, he sang, but his voice and, with it, the drama came close to being lost altogether in the Venusberg scene. He rallied and, a similar yet less extreme example in the Rome Narration notwithstanding, showed great professionalism in doing so. It was not a great omen, though, and seemed to unsettle audience and cast alike—maybe, to be fair, it did the conductor too. Otherwise, Vinke’s straightforward way with the role had much to be said for it: no great revelations, but capable of despatching it, clear of words and musical line, and physically enthusiastic. Lise Davidsen, though, was the true star of the show, as she was when I saw her previously in this role, at Bayreuth in 2019. She strikes a wonderful balance between Nordic cool (a reprehensible yet perhaps inevitable cliché) and warm humanity, as indeed she has in everything in which I have heard her. There is no doubting her ability to sing Elisabeth; that is a given. But she does much more with it too, whilst leaving the character open to our own thoughts. Arguably, Elisabeth will always remain something of an enigma, and that is no bad thing; or, alternatively, for her to be more than that, Wagner would have to have rewritten the part, and he did not.

%20LISE%20DAVIDSEN%20%C2%A9ROH%20Tannh%C3%A4user%2023%20Ph.Clive%20Barda-250%20adj.jpg)

Anyone daring to succeed Christian Gerhaher as Wolfram as his work cut out, but Gerald Finley succeeded in making the role his own through song; not, I hasten to add, that this was not a well-acted performance too, for it was, but rather that it was musically and, indeed, verbally conceived in the first instance. Ekaterina Gubanova’s Venus held the stage through abundant personality, of stage and vocal varieties. Mika Kares’s Landgrave cut a powerful presence. Sarah Dufresne’s beautifully sung Shepherd had one wish the part might be extended. The Royal Opera Chorus was on very good form, well prepared by William Spaulding.

Nevertheless, firmer hands on the ultimate rudders, both scenic and musical, would have lifted the evening considerably. Is Wagner, as sometimes I have heard claimed, to blame, here, for still owing us his later thoughts on (and with) the work? That would be far too easy a get-out clause.

Tannhäuser may not be perfect; it may not even be finished, or capable of being finished. But I am not the only one to have seen and heard other, more convincing near-solutions to its riddles. From Barenboim to Thielemann, from Götz Friedrich to Tobias Kratzer, it can be done. Oddly, though, my impression is that a number of the shortcomings on offer here, as well as the virtues, may actually have set many in the audience thinking about the nature of the work and its problematical dramaturgy. Perhaps it is time to intone, affecting an Anglican rather than Catholic or Lutheran voice, that we all, ‘in a very real sense’, still owe the world a

Tannhäuser.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20LISE%20DAVIDSEN%20%C2%A9ROH%20Tannh%C3%A4user%2023%20Ph.Clive%20Barda-250%20adj.jpg)