Variations on ‘Ich bin der

Schneider Kakadu’ for piano trio in G major, op.121a

Piano Trio in E-flat major,

op.70 no.2

Piano Trio in B-flat major, op.97,

‘Archduke’

Michael Barenboim (violin)

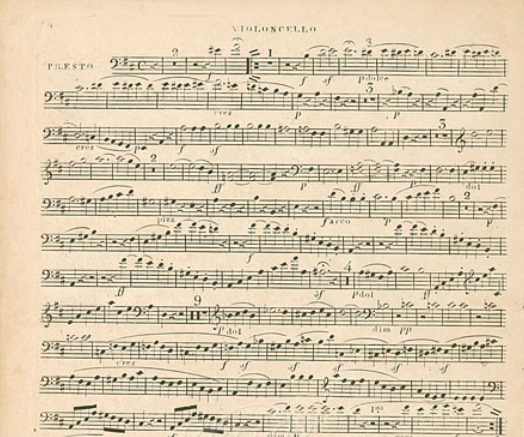

Kian Soltani (cello)

Daniel Barenboim (piano)

This, the second instalment of Beethoven

piano trios from Michael and Daniel Barenboim and Kian Soltani brought

almost as much joy as the first. If compelled to choose between the two, I

should have opted for the previous afternoon’s performances. Here, if only by comparison,

there were a few minor instances in which violinist and pianist seemed to lack

the final ounce of commitment we head heard previously, though such was never the

case from the outstanding Soltani on cello. Fortunately, there was no compulsion

to choose; instead, I learned much from hearing these works programmed and

performed as they were.

The performance of the opening ‘Kakadu’

Variations made as strong a case for this strange work as I have heard,

immediately announcing that this was once more to be the truest of chamber

music, listening, encouraging, and responding as equals. Daniel Barenboim as

pianist may have been the biggest ‘name’, yet he was here very much a

colleague. The introduction, so oddly out of kilter with the rest of the work,

was spacious, mysterious, expressive without exaggeration of an often

surprising degree of chromaticism. The advent of the theme, taken from Wenzel

Müller’s opera, Die Schwestern von Prag,

made me smile—though that did not seem to be the general audience response. We

heard a lovely, characterful parade of variations, all well pointed, and played

with all the care and attention that would have been lavished on more ‘serious’

music. I especially loved the syncopated exchange between Michael Barenboim and

Soltani in the sixth variation and the insouciant two-part writing, again

between violin and cello, in the seventh. Beneath and surrounding that lay Daniel

Barenboim’s lifetime’s experience not only in playing and conducting Beethoven,

but in thinking and rethinking about this music.

The introduction to the op.70

no.2 Trio spoke with all the depth and mastery of maturity: Beethoven’s, yes,

but surely these musicians’ too. What depth there was in particular to the

cello tone, Soltani as previously mentioned on very top form throughout. Both

here and elsewhere, I greatly appreciated the players relishing rather than in

any sense toning down the music’s difficulty. Those possessing performatively

jaded palates may complain about the composer’s prominence in concert

programming; if they truly listened, we should hear no more silly objections.

For here was classicism liquefying before the ears and fingers, the forms

Beethoven had inherited both negated and preserved: aufgehoben, to use that indispensable, untranslatable German term. (‘Sublated’ comes closest, I suppose, yet that seems better suited to philosophy than music,

insofar as the two may be disentangled.) The Wagnerian melos of the first movement’s development section could hardly be

faulted—and why should anyone try? If the second movement opened in strangely

casual fashion—perhaps a longer break between movements would have been better?—the

rest of the movement emerged in charming, sophisticated, yet never too

sophisticated fashion. Soltani’s lute-like pizzicato proved an especial joy.

Sterner passages were equally well handled, fine attention paid by all to their

specific demands. As ever, there was no hint of one size fitting all. The

minuet sang with a sunny integrity typical of Beethoven in this key (A-flat

major, rather than the ‘expected’ E-flat). Its C major trio’s strange

Romanticism seemed, quite rightly, more than a little suggestive of

Mendelssohn. Returning to the tonic, E-flat, for the finale, that return was

felt, not merely voiced, in a spirited, ebullient, yet variegated performance.

If occasionally I felt, especially earlier on, that it could have been more

clearly directed toward its goal, perhaps that was just me. In any case, there

was a great deal to absorb and, once again, no attempt to conceal the work’s

difficulties.

All good things must come to an

end, and what better way to do so than with the ‘Archduke’ Trio? The opening of

the first movement can readily sound too emphatic. Not here, Daniel Barenboim’s

relaxed wisdom just the thing as gateway to the work as a whole. There was, I

think, greater tempo variation here than previously, yet never for its own sake

and always rewardingly so. A particular type of middle-period Beethoven melodic

writing and its implications were captured to a tee in the development, Soltani

once more noteworthy in his combination of the moving and commanding. Sheer ‘naturalness’

of return to the tonic was something to be relished; so too, was ongoing

further development to the close. Throughout, detail and a sense of whole were

held in fine, productive balance. The scherzo sang and danced delightfully; its

trio’s counterpoint proved darkly even disconcertingly mysterious, piano

outbursts hinting intriguingly at Chopin. The slow movement’s ‘second

simplicity’ emerged in a reading of rapt sublimity. I could have done without snoring

from the row behind; such, I suppose, is part of life’s rich tapestry. What a

world, in any case, we had travelled from the variations with which the concert

had begun. Exalted good humour characterised the finale, both light and

profound as required, often in simultaneity.