(Article, ‘Über Staat und

Religion,’ first published in The Cambridge Wagner

Encyclopedia, ed. Nicholas Vazsonyi

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013))

|

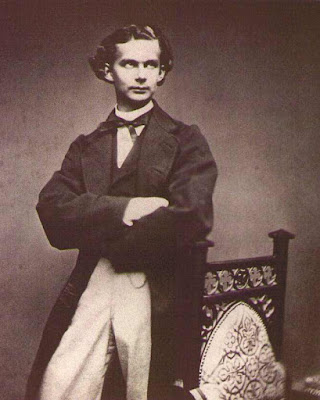

| Ludwig II, 1864 |

The

strategy resembles that of the contemporary Mein

Leben. Not least on account of the works’ common – royal – addressee,

Wagner presents himself as a revolutionary primarily for the sake of (his) art.

Such an attitude would eventually also characterize the Bayreuth Circle; some may even have believed that.

Nevertheless, the strong relationship between politics

and aesthetics endures. Wagner

claims political interest to be a reflection and product of artistic concerns;

ensuing discussion of his aesthetics immediately renders the relationship

dialectical, just as when he had tilted the scales towards politics earlier.

Moreover, Wagner does not disavow but revisits and sometimes reiterates certain

key socialist themes from Dresden

and Zurich, for instance abolition of the state and overcoming the

constrictions of modern labor. He distances himself from a form of “newer socialist”

distribution to which he had never subscribed in the first place (SSD 8:5). The word is killed that the

spirit might live.

Schopenhauer is the principal agent of

intellectual as opposed to circumstantial transformation, though the

distinction is not always clear. The blind striving of Schopenhauer’s Will

paints humanity less optimistically: egoistic individualism requires societal

stability (Stabilität), which

individuals have for their own protection invested in the state. Schopenhauer’s

Wahn (illusion) bids individual hopes

express themselves in patriotism, embodied in the monarch. (This need not

entail a nation-state; Bavarian particularism would be just as well served

here.) Monarchical independence furthers a number of related purposes,

including restraint of the base commercial imperatives of the press – Wagner

would soon be in need of that – and inspiration to redeem life by rising above

it. Monarchy appears a political and

metaphysical necessity. No revolution

– Wagner cannot quite bring himself to use the word – has ever failed to result

in restoration of that ideal representation of the state.

In

a new twist upon his idea of republican monarchy as adumbrated in the 1849

speech to the Dresden Vaterlandsverein, the king, as self-sacrificing “saint” –

in the vein of Schopenhauerian renunciation – dispenses “grace” (Gnade), rising above any particular

interest, his own or others’. State power is mitigated and ultimately negated

by two higher, ascending forms of Wahn: religion

(avowedly not theology: Feuerbach’s distinction still holds) and

art. Art’s superiority over religion as announced in the opening of Religion

und Kunst – no one believes art must be “true” – is foreshadowed.

Reading between the lines, artistic patronage would seem a good practical

example of how Wahn might be

harnessed, Hans Sachs-like, to

public good as well as princely salvation. Ludwig’s response seems to have been

of that ilk.