Grand Théâtre de Provence

Renata – Aušrine Stundytė

Ruprecht – Scott HendricksSorceress, Mother Superior – Agnieszka Rehlis

Mephistopheles, Agrippa of Nettesheim – Andreï Popov

Faust, Heinrich, Inquisitor – Krzysztof Bączyk

Jakob Glock, Doctor – Pavlo Tolstoy

Mathias Wissmann, Host, Porter – Łukasz Goliński

Hostess – Bernadetta Grabas

First Young Woman – Bożena Bujnicka

Second Young Woman – Maria Stasiak

Mariusz Treliński (director)

Boris Kudlička (set designs)Kaspar Glarner (costumes)

Felice Ross (lighting)

Bartek Macias (video)

Tomasz Jan Wygoda (movement)

Małgorƶata Sikorska-Misƶcƶuk (dramaturgy)

Dancers

Chorus of the Polish National Opera (chorus master: Miroslaw Janowski)

Orchestre de Paris

Kazushi Ono (conductor)

|

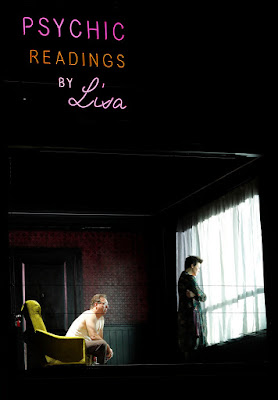

| Images: Festival d’Aix-en-Provence 2018 © Pascal Victor / artcompress |

The footballing World Cup final

made it unusually challenging to walk between the Théâtre

du Jeu de Paume and the Grand Théâtre de Provence in time for my last Aix

performance this year. Various thoroughfares were blocked as crowds gathered to

watch the proceedings on screens across the city. Still, tired, overheated, and

at times deafened by the noise of car horns, my friend and I made it, the

journey definitely worth the struggle for this Fiery Angel. Mariusz Treliński did what he seems to do best: a

‘modernised’ yet essentially straightforward production, Boris Kudlička’s often

spectacular set designs, Kaspar Glarner’s costumes, and Felice Ross’s lighting

very much an integral part of that. Generally excellent vocal and stage

performances offered much to enjoy and to provoke too.

Probably Prokofiev’s greatest

opera, The Fiery Angel is, almost

incredibly, based on a true story, that of Nina Petrovskaya, as told in Valery

Bryusov’s Symbolist roman à clef. And

yet, on the other hand, one might say it would have to be, for who on earth

could invent so bizarre and seemingly incoherent a tale of demonic possession?

Bryusov, again, one might say, for the tale is also invention, purporting to be

a translation of a sixteenth-century manuscript, glorying in the excessive

title, The

Fiery Angel; or, a True Story in which is related of the Devil, not once but

often appearing in the Image of a Spirit of Light to a Maiden and seducing her

to Various and Many Sinful Deeds, of Ungodly Practices of Magic, Alchemy,

Astrology, the Cabalistical Sciences and Necromancy, of the Trial of the Said

Maiden under the Presidency of His Eminence the Archbishop of Trier, as well as

of Encounters and Discourses with the Knight and thrice Doctor Agrippa of

Nettesheim, and with Doctor Faustus, composed by an Eyewitness (translation, Richard Taruskin). Treliński

captures that dichotomy well in some ways, less well in others. Perhaps,

however, that will be the fate of any attempt to manage this unmanageable work,

all the more so when it assumes operatic form.

His method is very much to emphasise

realism until he can do no other, and to explain away or, perhaps better,

account for some of the most surreal aspects, again until he can really do no

other. Renata, then, is a very sad case already: a product of disadvantage of

abuse, whose hallucinations, like those of many in the society around here,

seem very much to be the product of narcotic substances. The charlatanry of the

incomprehensible – to me, anyway – figure of Agrippa of Nettesheim is clear; or

is it? How much are his multiple appearances, both to Renata and to the

well-meaning if lustful Ruprecht, entirely the doing of a trip induced by their

dealer, Jakob Glock? That we cannot entirely make sense of what is going on

seems to me all to the good. Hallucinatory (we think) appearances of characters

on all three levels of the set are far too much for any of us to take in at one

setting: they are frighteningly real and yet at the same time clearly not at

all real. Or some of them are, and some of them are not; we never really know. Yet

is this perhaps not what might have been going on all along in the ‘original

manuscript’? There is an oddly prevalent modern belief that drugs, their use

and abuse, are somehow something new. Extreme, erotic ‘religious’ experiences

and such causes, are anything but new, however. One only has to think of the

visions of saints – who so very often had also been the basest of sinners. And

so, the updating to a tawdry, flashy modern world of design hotels, sex shops,

and gurus, is both true and untrue to the work – which, I think, is probably

how it should be. One may make something of the knock-down Vegas walk-on parts

or not, just as one might or might not in ‘real’ or ‘hallucinogenic’ life (or

death).

Doublings are put, as if in Lulu, to excellent dramatic and not

merely practical use. (If one wants ‘practical’, one might be better off opting

for another opera.) Jakob Glock is also the Doctor; we think, perhaps, they are

narcotic accomplices. Perhaps indeed they are, for are we quite sure that one

is not an ‘actor’ – whatever that might mean in this context – and one is not?

Mephistopheles and Agrippa of Nettesheim are one and the same – perhaps. Quite

what we are to make of the scene in which Mephistopheles and Faust appear is in

any case anyone’s guess. Perhaps most

tellingly, Heinrich, the object of Renata’s fixation is also not only Faust but

the final act’s Inquisitor. There is something not only of the charlatan but,

chillingly, the blind Jimmy Savile (!) to him too. Not for nothing do further visions

– Renata’s, presumably, but who knows? – hark back to childhood, to gymnastic

exercises, to an army of little Renatas in preparation for – well, preparation

presumably for this. The notorious concluding convent orgy both does and does

not happen. Is it all in her imagination, and is she now in hospital? Those

expecting the acrobatic experiences of David Freeman’s celebrated Mariinsky

production will be disappointed, which seems in part to be the point, but

perhaps also intrigued, even moved to reflect. We do not always see and

experience what we want to, however potent the drug, the magic, the God.

Prokofiev places Renata very

much at the centre of the work: too much, some have said. Taruskin refers to ‘one of the reasons for the opera’s

continued neglect’ beingf its unusual fixation on a single very difficult – and

dramatically static – role,’ a state of affairs Prokofiev may well have

rectified had he proceeded with his intended 1930 revision. I am less convinced

that it is a problem, although lessening – I should not go so far as to say

removal – of the novel’s autobiographical focus on Ruprecht certainly has its

consequences. Whatever one thinks about the undoubted domination of the opera

by the soprano in the abstract, it was surely vindicated in performance by the

magnificent Aušrine Stundytė: obsessive, hysterical, and alarming, yes,

but also vulnerable, human, and above all capable of expending an extraordinary

range of colour, emotion, and dynamic contrast. Scott Hendricks’s Ruprecht had

its moments, but he seemed less comfortable in the role. (Not that comfort is

really the thing, here, I suppose.) ‘Weak’ roles are a difficult thing, of

course; ask any Don Ottavio. However, I could not help think that he might have

projected his own dilemma more strongly in musical terms. His Russian also

seemed to me – this was confirmed by a friend who actually knew! – often quite

indistinct. Otherwise, the host of bizarre characters came and went, starring

as and when they could, almost all of them making strong impressions in their

weird and wonderful ways. Andreï Popov, Pavlo Tolstoy, and Bernadetta Grabas,

were perhaps first among equals here, but in such an ensemble piece, in such an

ensemble performance, the whole proved considerably greater than the sum of its

parts.

The other slight disappointment

lay in Kazushi Ono’s direction of the Orchestre de Paris, especially earlier

on. This was a fluent enough reading, which achievement deserves praise in

itself, but a lack of bite in the first two acts in particular was often

noticeable. Perhaps it was a reluctance to overpower the singers: surely a

misguided reluctance in an opera such as this, in which so much is a manic

struggle that may or may not ultimately make sense. The Polish National Opera

Chorus sang splendidly, however, full of heft and far from without subtlety –

except, of course, where subtlety is the last thing one wants to see or hear.

Which, in this work…