York Hall, Bethnal Green

|

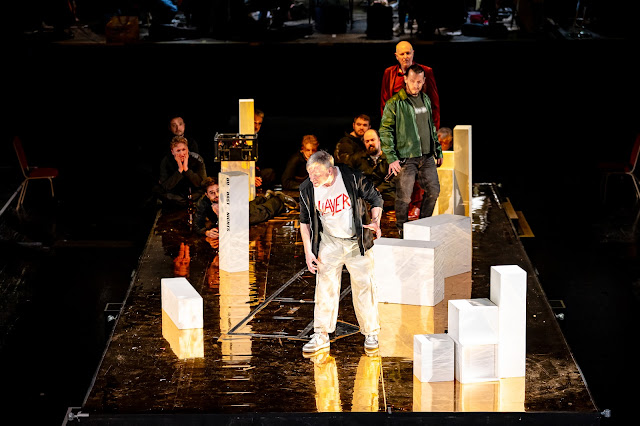

| Images: Steve Gregson Siegfried (Peter Furlong), Hagen (Simon Wilding), Gunther (Andrew Mayor) |

First Norn - Ingeborg Novrup Børch

Second Norn, Flosshilde – Mae Haydorn

Third Norn, Woglinde – Jillian Finnamore

Brünnhilde – Catharine Woodward

Siegfried – Peter Furlong

Gunther – Andrew Mayor

Hagen – Simon Wilding

Gutrune – Justine Viani

Waltraute – Catherine Backhouse

Alberich – Oliver Gibbs

Wellgunde – Elizabeth Findon

Vassals – Davide Basso, Max Catalano, Anthony Colasanto, Jacob Dyksterhouse, Tim Sawers, Alfred Mitchell, Ed Walters, Robin Whitehouse, Guy Wood-Gush

Assistant directors – Eleanor Strutt, Keiko Sumida

Designs – Isabella van Braeckel

Lighting – Patrick Malmström

Producer – CJ Heaver

Members of London Gay Men’s Chorus

.jpg) |

| The Norns (Ingeborg Novrup Børch, Mae Heydorn, Jillian Finnamore) |

Wagner’s Ring is the drama of our time, yet it is surely the drama of every time. Seeing Opera North’s concert Rheingold only five days after the fateful 2016 referendum, the work seemed to take its leave from that. In our present malaise, Götterdämmerung inevitably seems closer than ever. Wagner, after all, pointed to the great virtue of myth being its alleged truth for all time, its content inexhaustible for any age. He is not saying quite the same thing there, although nor is he saying something entirely different. Tempting though it might be to proceed down that road, the particularity of this particular production and performance should be our primary concern. If my personal experience was less than ideal, in that I was unable to see Die Walküre and Siegfried, the final day of Wagner’s Ring spoke mostly for itself, with tantalising suggestions of what I might have missed—and dearly wish that I had not.

Caroline Staunton’s production continues to tell the story with great intelligence and clarity, further framing refreshing rather than distracting. The sense of a collection of objects, a museum or gallery even, has developed since Rheingold’s contest of Valhalla and Nibelheim, to something less distant, incontestably ‘present’, as many of the best Götterdammerungen have always been. In any Ring, thoughts almost inevitably turn to that of Pierre Boulez and Patrice Chéreau: testament not only to its extraordinary quality, almost taking upon itself that mythical quality to which Wagner referred, but also to its historical fortune, falling in the right place at the right time, and with the right technology (television) spreading its word. This is unquestionably, as Chéreau remarked and showed, a post-religious society of increasingly desperate rituals, which knows no morality and finds it difficult, perhaps impossible, to ‘know’ at all. Here, the sense of objects curated, possessed, and, like the gold, fatefully valued – an ‘art market’ not so very different from what one might encounter, say, in the Tate Modern’s Turner Prize – entwines with Wagner’s epic, genealogical method, verbal and musical, of telling, retelling, adding standpoints and perspectives, never repeating. The world of the Norns seeks, perhaps, to protect objects gathered from earlier instalments. One can see and feel this when, as a gallery spectator, one ventures during the intervals to inspect the saucepan and tins, presumably Mime’s, from Siegfried, and other such objets.

|

| Hagen, Gunther, Brünnhilde, (Catharine Woodward) Gutrune (Justine Viani) |

The following world of the Gibichungs glories, trivially yet palpably, in their extraction and abstraction, in the fetishist need to add to the collection, as Alberich needed to add to his hoard, Wagner’s furchtbare Not turned Lacanian. (We might reflect on that as we seek to add to the collection of Ring performances we have seen. Why are we doing this? Is it as mere collectors, perhaps closer to Nietzsche’s ‘Wagnerians’ or as something more active, as participants, as the revolutionary audience Wagner himself demanded?) I could not help but think of the denizens of Frank Castorf’s Götterdämmerung safeguarding their Picassos as Brünnhilde, purposely underwhelmingly, set Wall Street (slightly) ablaze. That consumerism appears to be what drives Gunther and Gutrune to wish to acquire Siegfried and Brünnhilde, though Hagen of course knows better and deeper. When all is returned to the Rhinemaidens, one can read this in all manner of ways; an ecological imperative is not necessarily to the scenic fore, though it hardly need be, since it will surely present itself to any thinking person in the midst of our climate emergency.

Instead, we are prompted to think of the role art and its commodification, as well as more general sliding into the ‘mere’ craft, indeed ‘effect without cause’ Wagner diagnosed in the more meretricious would-be art of his own time. Paris, the capital of the nineteenth century, is transposed to the Ring in a Bethnal Green boxing ring. And the ring itself, like various of these objects more akin to Loge’s Rheingold toyland ‘Tand’ than the fearsome object we have been led to believe, gains whatever power it might have through the act of investing. It is less a matter of it working on account of belief, than on account of its valuation, or perhaps better a financialised, late-capitalist merging of the two; until, that is, the bottom falls out of the market, as it always will, rope of Fate or otherwise.

|

| Gunther, Brünnhilde |

Conductor Ben Woodward and his small ensemble continued to work wonders. Of course there are times when one longs for a full orchestra, just as in a large theatre, there are times when one longs to be able to see the faces of those onstage. What surprised was how relatively few they were. Götterdämmerung surely presents the toughest challenge in this sense of the four dramas. Das Rheingold as Kammerspiel makes considerable sense, but the cosmic scale and grand opéra hauntings of this tale of Siegfried’s death and Brünnhilde’s redemption, heard through all that has passed before, seem to require something different. Maintaining tension over its vast span is difficult enough at Bayreuth or Covent Garden. Even the most exalted orchestras will slip here and there. This, however, was decidedly not the moment for Beckmesserish quibbles. Musical drama unfolded with care and intelligence, in tandem with the staging yet far from enslaved to it. Opportunities to hear it anew, sometimes even a little ‘inside out’, were gladly taken, forming part of an overall refreshment for the jaded, as well as a riveting introduction for those enabled to attend for the first time. The instrumentalists deserve nothing but praise for their contributions throughout, and choral forces brought welcome and, in this context, all the more telling contrast, permitting that larger-scale operatic world thrillingly to burst in.

|

| Hagen |

None of this could, of course, have been achieved without the contributions from an excellent set of singing-actors. Different audience members will have had different favourites, and all contributed to a drama that was very much greater than the sum of its parts. Nonetheless, I was particularly struck by Simon Wilding’s Hagen and Catharine Woodward’s Brünnhilde (partly the roles, no doubt, though only partly). Wilding’s Hagen, dark and dangerous, simply owned the stage, a study in evil and its undeniable charm. The scene with his father proved especially moving, Oliver Gibbs not so much reprising as developing his outstanding Alberich for new, still darker times. Woodward’s Brünnhilde was similarly blessed of stage presence. Art in many respects conceals art: it was difficult not to feel that this simply ‘was’ the Valkyrie, and these simply ‘were’ the final phases of her journey. She could certainly sing too, offering an Immolation Scene of equal humanity and grandeur, in tandem with conductor and orchestra. It seemed, then, in many ways fitting that, at the end of the second-act trio, perhaps haunted here more by Verdi than Meyerbeer, Staunton should offer the twist of an unexpected passing union between Hagen and Brünnhilde.

Gunther and Gutrune offer different challenges, of course. Vocal portrayal of weak characters is always a tough call, to which Andrew Mayor and Justine Viani rose very well indeed. The key, it seemed, lay in portrayal arising from the text, as was also the case with Peter Furlong’s tireless Siegfried, the character clearly, intriguingly traumatised. I suspect a clue to this would have been found in Siegfried; even without, it pointed to the difficulties our age and indeed Wagner’s (later Attic tragedy too, for that matter) have found in heroism. Catherine Backhouse gave a heartfelt reading of Waltraute’s pleading. Norns and Rhinemaidens emerged in fine ensemble, without sacrifice to individual voice.

To conclude, then, may I once again suggest that any reader feeling able to do so might consider supporting this extraordinary venture, thrice denied Arts Council funding? The ecology of opera in this country is now as parlous as that of the world around us. Maybe, just maybe, Götterdämmerung can still be averted.