‘Yes, I should like to perish in Valhalla’s flames! — Mark well my new poem — it contains the beginning of the world and its destruction!’ Wagner’s words in an 1853 letter to Liszt, a copy of the Ring poem enclosed, express abiding theatricality, often overlooked, despite Nietzsche’s vicious attack on Wagner as ‘actor’. They point also to his framing of the Ring dramas on which he had been at work since 1848 and whose completion would lie more than two decades hence, in 1874.

|

| The Immolation Scene from the 'Centenary' Ring Copyright: Bayreuth Festival |

It is well known that Wagner wrote his poems in reverse order, beginning with Siegfrieds Tod, soon to become Götterdämmerung, and needing to write three prequels, before composing the music in the order we know today: the trilogy ‘with preliminary evening’. Likewise that he broke off composition of Siegfried to write Tristan and Die Meistersinger; likewise that he found it necessary to write a number of verbal endings to Götterdämmerung between 1848 and 1856 before resolving upon the ‘wordless’ solution, or rather enigma, with which he continues to tantalise us. But the consequences for his dramas are often misunderstood. Wagner’s thought always tended towards an amalgam of the agglomerative and the synthetic. That characteristic renders him especially attractive to the historian of the nineteenth century. Ideas and influences overlap, not necessarily supplanting or resolving, but heightening conflict, the very stuff of drama, thereby rendering him especially attractive to audiences and to performers. Not every idea and influence need be reflected in every performance; were that attempted, we should most likely end up with an unholy mess. However, not only will any production, indeed any audience, have to make choices; they also need to consider what is being left out, or at least played down.

Feuerbach, Bakunin, Marx

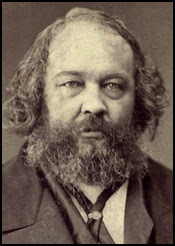

|

| Bakunin |

|

| Feuerbach |

Wotan and Alberich, Valhalla and Nibelheim

And so, in

the Ring, Wagner unmasks – a favourite

Young Hegelian conceit – the realm of the gods, built not upon that first

‘natural’ opening to the cycle, but arising from the second, counterpoised genesis,

as told by the Norns in the Prologue to Götterdämmerung.

Not that the first is so straightforward as it might seem, for Nature, in the

guise of the Rhinemaidens, acts cruelly to Alberich, denies the misfit dwarf

love, and is violated by him in turn; there is no golden age in the Ring-cosmos. That said, the natural

world stands preferable to the deeds of Wotan, chief of the gods and thus in

some sense a representation of the godhead itself. Inscribing runes upon his

spear, Wotan commits the primal sin of politics, defining principles which,

even had they once been good in themselves, become outdated as soon as they

find themselves represented in dead wood. Fricka, according to Wagner the voice

of ‘custom’, simply cannot understand this, lamenting with all the outworn

moralism of a believer who has forgotten quite why she believes, that Siegmund

and Sieglinde should love one another. We never see her again, though she will

be invoked, off-stage – out of Heaven? – by Hunding, not that she can help him,

and as the recipient of vain burnt offerings in Götterdämmerung. Her day has passed.

The spear is also an instrument of domination; it is with military force as well as ideology that Wotan rules the world. Yet ideology in a sense comes first, which is why Valhalla is built, as much a religious as a political fortress, a classic instance of European ‘representational’ culture, which ‘re-presents’ its power to subjects who must be overawed. For, as Wagner and Bakunin were convinced, the ‘critique of religion is the essential precondition for all criticism’ (Marx on Hegel): that of Alberich’s capitalist tyranny of Nibelheim with its golden hoard, the modern factory incarnate, as well as Wotan’s more sumptuous, more ideologically complex castle in the air. It is intended, in the words of the celebrated Lutheran chorale, as ‘ein’ feste Burg’ (‘a stronghold sure’), yet note that it appears first of all to Wotan in a dream. In Feuerbach’s proclamation: ‘Religion is the dream of the human mind,’ in which ‘we only see real things in the entrancing splendour of imagination and caprice, instead of in the simple daylight of reality and necessity,’ a view lent Wagnerian credence by Pierre Boulez’s observation, voiced whilst working on the Bayreuth ‘Centenary’ Ring, that our first musical encounter with Valhalla ‘is not clearly delineated but belongs to a world of dream, phantasmagoria, and mirage.’ Moreover, the forced, disturbingly empty grandeur, or rather grandiosity, of Das Rheingold’s closing bars tells already of desperation, unnatural prolongation, deceit, and, as Erda has already foretold, ‘a dark day [that] dawns for the gods’. Freia and her golden apples may have been regained, but we have seen behind the throne, as has Alberich. Both Alberich and Licht-Alberich – the Wanderer, in his riddle-confrontation with Mime styles himself ‘Light-Alberich’, his ‘black’ antagonist’s power-seeking alter ego – commit crimes against Nature, one despoiling the Rhine, one sapping the life from the World-Ash Tree; both wish to extend that power through possession of the ring, forged in denial of that love, which was for Feuerbach the foundation of a true, human religion; both can be unmasked and thereby overthrown by extension of religious criticism beyond the ‘merely’ theological; and both have their deeds dialectically connected in the musical metamorphosis between the first two scenes of Das Rheingold of Alberich’s ring into Wotan’s Valhalla.

Loge, critic and god of fire

Built upon false contracts, entered into with Fasolt and Fafner,

which was for guaranteed by Wotan’s very own spear of domination, and

perpetuated by continued denial of the gold to the Rhine and its daughters,

Valhalla and the gods’ rule are fatally compromised from the outset. The gods’ entrance,

punctured by the Rhinemaidens’ plaints and Loge’s (Young Hegelian) criticism –

‘They hasten to their

end, they who imagine themselves so strong and enduring’ – is already a dance of death, rendered all the more slippery by

the destabilising, negating, almost Faustian chromaticism of Loge’s motif. Not

for nothing has he been identified as the Ring’s

sole intellectual, and, when one bears Bakunin and indeed the Wagner who

prescribed a ‘fire-cure’ for Paris in mind, one realises that there lies no

contradiction whatsoever between Loge’s twin roles as critic and as god of fire.

Moreover, Loge’s ‘imagine’ (wähnen)

is crucial not only in the Feuerbachian sense, but also in that it provides, in

its anticipation of the Wahn

(‘illusion’) of Schopenhauer, whom Wagner had not yet read, a textbook example

of a concept that would acquire additional layerings of meaning as Wagner’s

work on the cycle and elsewhere proceeded: recall Hans Sachs’s ‘Wahn, Wahn,

überall Wahn!’

The ‘purely human’ Volsungs

The contrasting

world of the ‘purely human’, a term Wagner often employed in his theoretical

writings, is experienced with vernal, magical immediacy in Die Walküre: ‘You are the Spring,’ Sieglinde exults, before

submitting to her brother, the curtain falling only just in time, as the music’s

passion requires us all to take a metaphorical cold shower during the interval.

Feuerbach abides here, for not only does this celebrate love between Siegmund

and Sieglinde; it commemorates Siegmund’s rejection of Valhalla, echoing

Feuerbach’s Thoughts on Death and

Immortality, whose opening pages include a ‘Humble petition to the exalted,

wise, and honourable learned public to receive Death into the Academy of

Sciences’:

He is

the best doctor on earth;

none of his cures has yet failed;

and no

matter how sick you become,

he

completely heals Nature.

To be

sure, he never has concerned himself

with

Christian theology,

yet he

will have no peer

in

understanding philosophy.

So then

I implore you to receive

Death

into the academy,

and, as

soon as possible, to make

him doctor of philosophy.

What Siegmund accepts, celebrating death and his love for Sieglinde in heroic defiance of the illusory promise of immortality in Valhalla, Wotan struggles towards, at one point willing ‘the end’ and yet, even at the last in Siegfried, making a stand, unwilling quite to ‘die in the fullest sense of the word,’ according to Wagner’s words in an 1854 letter. It takes, moreover, a free act, albeit unconsciously free, by Siegfried, revolutionary hope of Engels and Wagner alike, finally to shatter Wotan’s spear of law, and to return the god for good to Valhalla, to await, in Schopenhauerian resignation, the end. Siegfried’s undoing will be his lack of consciousness, though that spontaneity will also point to his greatness, a dilemma which, as revolutionary hopes faded yet never entirely died, became all the more pressing for Wagner. Indeed, it is only in memoriam, in the shattering Funeral March, that Siegfried proves worthy of the hopes invested in him, of Wagner’s stated desire in the Ring ‘to make clear to the men of the Revolution the meaning of that Revolution, in its noblest sense’. No longer quite the hero of the drama that he had been in the more straightforwardly revolutionary Siegfrieds Tod, Siegfried has neither quite triumphed nor quite been supplanted: again, Wagner’s intellectual method poses rather than answers questions.

Concluding, thinking,

making sense of uncertainty

To have written that the dramas were

completed in 1874 was in a sense misleading, for they remain magnificently

open-ended, whether in performance or staging. The composer was notably

dissatisfied with scenic realisation at Bayreuth. Wagner’s great effort to

conclude remains, whatever his own ambitions towards Hegelian totality,

stubbornly necessitates further questioning. This may be of the nature, ‘What

happens to Alberich?’, not at all a silly question. Does such uncertainty of

plot, hardly accidental, suggest that, whatever the ‘watchers’, the mysterious

‘men and women moved to the very depths of their being’, at the end of Götterdämmerung may have experienced,

even learned, that we are doomed to repeat the cycle ad infinitum? Such, after all, is the implication of a cycle,

though what of Warner’s and Stefanos Lazaridis’s double helix, perhaps

suggestive of Hegel’s favoured spiral? Indeed, whilst the ring itself tempts us

to think in circular form, we should always bear in mind that, more often than

not, its powers are ‘unmasked’ as

illusory. All forms of power, love included, fall prey to Wagner’s deconstruction

and savage indictment – his encounter with the philosophy of Schopenhauer here

fuses with prior disillusionment with the more naïve aspects of Feuerbach’s

‘love-communism’ – and yet we continue

to ask ourselves whether a world without power is even conceivable, or merely

‘utopian’, to borrow from Marx and Engels. Siegfried is never better off than

when he values the ring at naught; Brünnhilde is never worse off than when she

considers it to betoken marriage, another form of property-based power. (The

socialism of French writers such as Charles Fourier, with its celebration of

something akin to what another generation would call ‘free love’, was always a

potent ingredient in Wagner’s intellectual mix, likewise that of Pierre-Joseph

Proudhon, whose most famous slogan remains ‘Property is theft’, instantiated in

Alberich’s conversion of value-free Rhinegold into capital.)

Thus particular questioning readily transforms itself into the more general, conceptual variety, and vice versa. That whole ‘world’ of which Wagner wrote to Liszt develops before our very eyes and ears, both in performance and in subsequent contemplation. The Ring’s web of motifs encourages us to think in such a way, to dart back and forth, reminding us of its world’s past, hinting at its future, and tantalising us with alternative paths of development, which intriguingly become all the more ‘real’ the more strongly we know that they will be denied. What if…? This is not a work one can know too well, or even well enough. And yet, we know ,with Hegel, that the owl of Minerva only spreads its wings at dusk; or, with Marx, that it is folly to write recipes for the cookery books of the future. It is no coincidence that Hegel and Marx were so taken with early theories of evolution, with their strong facility of backward explanation and their weak predictive powers. Wagner might speak theoretically of the ‘artwork of the future’, but he is wise enough in that artwork to stick to the past and present; he does not present us with science fiction. The world is rightly given over to the ‘watchers’.

What

about us? We might do well to heed Warner’s words, ‘When you are torn apart at

the end of Die Walküre – as I think

you should be – it’s because you’ve had five hours of profound information

about these people, not because you’ve been manipulated into weeping by mere

theatrical or musical devices.’ Wagner, in his own words, aims at

‘emotionalisation of the intellect’, not at its abdication. The Ring acts as a standing rebuke to those

people – Nietzsche might have called them ‘Wagnerians’ – who wish merely to

wallow. An audience, just as much as a performer or a director, which fails to

think is unworthy of the Ring, yet

that incitement affords an extraordinary opportunity. There is clearly

identification, albeit uncertain, to be had between us and the ‘watchers’ – we

are all survivors – and a crucial clue here is that they are human. The end of

Wotan’s rule is not hymned with words of revolutionary jubilation as it had

been in one of Wagner’s projected endings, the so-called ‘Feuerbach ending’,

yet there nevertheless remains a strong sense that, human though we may be in

our failings as well as our strengths, our world is that Nietzsche would herald

in The Gay Science:

We philosophers and ‘free spirits’ feel,

when we hear the news that ‘the old god is dead,’ as if a new dawn shone upon

us; our heart overflows with gratitude, amazement, premonitions, expectation.

At long last the horizon appears free to us again, even if it should not be

bright; at long last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any

danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our

sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an ‘open sea’.

There have been endless discussions as to

whether this conclusion is pessimistic or optimistic [in our shorthand,

‘Feuerbach or Schopenhauer?’]; but is that really the question? Or at any rate

can the question be put in such simple terms? [Patrice] Chéreau has called it

‘oracular’, and it is a good description. In the ancient world, oracles were

always ambiguously phrased so that their deeper meaning could be understood

only after the event, which, as it were, provided a semantic analysis of the

oracle’s statement. Wagner refuses any conclusion as such, simply leaving us

with the premisses for a conclusion that remains shifting and indeterminate in

meaning.