Komische

Oper, Berlin

|

| Images: Iko Freese | drama-berlin.de |

Petrushka – Tiago Alexandre

Neta Fonseca

Ptitschka – Pauliina RäsänenPatap – Slava Volkov

L’Enfant – Nadja Mchantaf

Le Feu, La Princesse, Le Rossignol –Talya LiebermanMaman, La Tasse Chinoise, La Libellule – Exgi Kutlu

Une Pastourelle, La Chauve-Souris – Elizabeth Holmes

La Chatte, L’Ecureuil – Maria Fiselier

L’Horloge comtoise, Le Chat – Denis Milo

La Bergère, La Chouette – Mirka Wagner

Le Fauteuil, L’Arbre – Carsten Sabrowski

Le Petit Vielliard, La Théière, La Rainette – Ivan Turšić

Un Pâtre – Katarzyna Włodarczyk

Suzanne Andrade and Esme Appleton (directors)

Paul Barritt (animations)1927, Pia Leong (set designs)

1927, Katrin Kath (costumes)

Diego Leetz (lighting)

Ulrich Lenz (dramaturgy)

Vocalconsort Berlin (chorus master: Andrew Crooks)

Children’s Choir (chorus mistress: Dagmar Fiebach) and Orchestra of the Komische Oper

Markus Poschner (conductor)

1927’s Magic Flute has been

well-nigh universally lauded, both at the Komische Oper and subsequently on

tour. I say ‘well-nigh’, since I

felt more ambivalent, applauding some aspects of the reworking, whilst

lamenting a lack of seriousness at its heart: for me a perennial problem with many

stagings of that work. Maybe I was not in a very good mood, or maybe the

combination of æsthetic and work was just not for me; maybe I missed the point.

Or perhaps I was right: who knows? I am not terribly easy to please when it

comes to Mozart. At any rate, I am delighted to welcome its successor, a

double-bill of Petrushka and L’Enfant et les sortilèges.

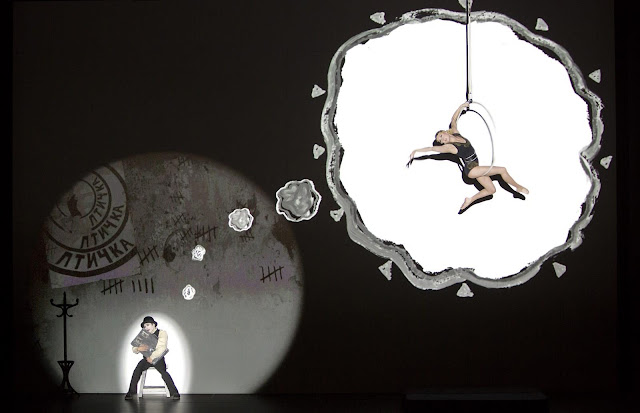

Petrushka is 1927’s

first completely non-verbal work, and, of the three I have seen, I think it

comes off best of all. (A counter-argument might be that I know less of ballet

than I do of opera, but I should like to think that I know a little about

Stravinsky, at least.) Here we see it via the offices, once again, of Paul

Barritt’s animation – and with three humanised puppets: Petrushka as ‘awkward clown’,

alongside a ‘sensitive acrobat’, Ptitschka, and an ‘unrefined but good-natured

muscle-man,’ Patap. The animations are a period-influenced, but not period-restricted,

delight: from a little later than the writing of the work, as the company’s

name, ‘1927’, might suggest. Russian constructivism and the world of silent

films more generally loom large. Colours, aptly, are gloriously bright (even if

the curmudgeon in me might have wished for the original score rather than the

more ‘practical’ 1947 revision), yet monochrome plays its part too. We tumble

headlong – not unlike Petrushka himself, a little later – into the world of the

fairground. ‘Roll up, roll up,’ the Russian speech-bubble (thank goodness for

the Komische Oper’s multi-lingual titles) beckons us; it really felt to me as

though we were making an individual and collective decision to attend the show

within a show.

That show is beautifully presented, not only showing but dramatising a

keen sense of the thin line between comedy and tragedy. Puppet shows have

always done that brilliantly, or at least the best ones have, so why should not

a multi-media reimagining of the format, a work about puppetry? Petrushka is the latter anyway, of

course, and here the figure of the puppeteer looms large – not visually,

although his (I think we can presume ‘his’) actions certainly do. The

heartlessness with which Petrushka is toyed with – which yet endears him to

Ptitschka, and indeed also elicits sympathy from Patap, following his necessary

moments of self-display – moves us, as does the excellence of the onstage performers,

seemingly effortlessly moving between the worlds of stage and film. The sad

clown, for Barritt close to Buster Keaton, and dressed as such, is not for

nothing one of our culture’s perennially recurring figures. He lacks the grace

of Ptitschka, the physique of Patap, but he is human, he feels sadness even

when, particularly when, he amuses us. The manipulator of his emotions – the puppeteer,

that is – does not entirely succeed in manipulating ours.

As for the other manipulator, the composer who so notoriously declared

music’s inability to express anything other than itself, his score in

performance exuded colourful rigour, its opening nicely, intriguingly

deliberate, as if the forces were limbering up yet undoubtedly in control. Like

what we saw, what we heard sounded audibly ‘Russian’ in origin and spirit, but

with some degree of distance from time to time as well: not unlike Stravinsky,

one might say. A few minor frayed edges aside – one can readily forget what a

difficult piece this is – the orchestra under Markus Poschner did it proud, reminding us that recreation is

not simply a matter of a new production; it happens, or should happen, every

time we play and hear Petrushka.

In a programme

interview, Suzanne Andrade likens the figure of the puppeteer in Petrushka to that of the Mother in L’Enfant et les sortilèges. It makes for

a good connecting motif: meaningful rather than merely neat. It also helps make

the ‘moral’ of Colette’s story – I think Ravel remains more circumspect; does

he not always? – both more explicit and open to question. (Perhaps it

criticises itself anyway; I am genuinely not sure. If so, that tendency is

stronger here.) Andrade says that she and her collaborators had originally

intended the boy (sung by a woman, let us never forget) to be like ‘one of

those upper-class boys from Great Britain … they are naughty and learn nothing

from the experience, because the societal status quo is such that they need not

learn anything.’ If those overgrown schoolboys (and their aspirant hangers-on)

have ‘had enough of experts’, we, not least those of us recently pushed into

exile, have had more than enough of their running amok with our lives and

futures; it is therefore something of a relief to experience contrition and

forgiveness, before asking ourselves: ‘but whose, and on what authority?’ Who

is the Mother, whether personally or more broadly, and what does she intend to

be the outcome of those trials through which she means to get her own way?

The visual

inspiration here comes from comics and films involving naughty little boys.

Andrade names Dennis the Menace and

the American film series, Our Gang

(which began in the 1920s). Again, the transitions between animation and

staging are deftly, wittily presented. (They also help with doubling or

tripling of parts: one need not always see the singer in costume.) If I did not

feel that as much was added to my thoughts about the work as in Petrushka, beyond that intellectual and

dramaturgical question of overarching agency, perhaps I am showing myself a

little more resistant, as I suggested, in opera than ballet (if, indeed we

consider Stravinsky’s work primarily as such). Perhaps I also missed the

nostalgia evident in Ravel’s sophisticated conception of childhood: no child

could or would ever think of its ‘hood’ like that. One might counter that the

score is there to do that anyway.

The Komische

Oper’s welcome change of language policy – are you listening, ENO? – meant that

we did not have to hear Ravel in German. If not everything was delivered with

the most assured sense of what we have come to accept as French style, it

rarely, or never is, even with Francophone singers. Moreover, one could hear

every word – which is not always the case with such singers. Nadja

Mchantaf made for a splendidly tomboyish boy – if that makes any sense. As

hapless and as clumsy as Petrushka, he will at least have another chance.

(Those privileged boys always do.) Orchestra and conductor seemed – or perhaps

this was just my imagination, given the context – to play the score as if

informed by some Stravinskian elements, rhythm perhaps playing a more prominent

role than harmony at times, although such hierarchies will always be a matter

of degree. In keeping with what we saw, there was much in bright, primary

colours, and an evident delight in the mastery of that ‘Swiss watchmaker’, as

Stravinsky called him. The rest of the cast proved very much more than the sum

of its parts. If I do not relist the singers, it is not out of disrespect, but

at least in part to emphasise, as so often in this house, the nature of the

achievement of the company in an emphatic sense.