|

| Images unless otherwise stated: (c) Jakob Tillmann |

Klytämnestra – Waltraud Meier

Elektra – Ricarda Merbeth

Chrysothemis – Vida Miknevičiūtė

Orest – Lauri Vasar

Aegisth – Stephan Rügamer

First Maid – Bonita Hyman

Second Maid, Train-bearer – Natalia Skrycka

Third Maid – Katharina Kammerloher

Fourth Maid – Anna Samuil

Fifth Maid – Roberta Alexander

Overseer, Confidante – Cheryl Studer

Young Servant – Siyabonga Maqungo

Old Servant – Olaf Bär

Orest’s Tutor – David Wakeham

Vincent Huguet (assistant director)

Richard Peduzzi (set designs)

Caroline de Vivaise (costumes)

Dominique Bruguière (lighting)

For many of us, she has always been there. Not only ‘there’, somewhere, but there—at the top. It is difficult not to romanticise a little, though it is certainly not her style. She spoke briefly and with customary professionalism: she had had a wonderful career, done what she wanted to, and now it was time to say goodbye. ‘Tschüss.’ And with that, Waltraud Meier – the reason all of us, however avid Straussians we might be, were there – bade farewell to the stage. I saw her last Kundry and her last Isolde. I even heard her Marcellina last year, reuinted with Siegfried Jerusalem as Don Curzio (!) We had just heard and, crucially, seen her final Klytämnestra.

Like the queen she portrayed with

intelligence, dignity, a fresh eye and ear, and as keen a collaborative

instinct as ever, this queen of the stage bewitched us once last time—and let

us go. The audience, however, did not seem inclined to let her go, however many

times the curtain fell. Bouquets continued to fly on to the stage, or

sometimes, not quite reaching their target, into the pit. The ensemble –

whatever fans might have felt, this was never a solo show – continued to come

forward to receive applause. Then, once again, she briefly stepped forward,

this time without microphone, to pay tribute to that constant presence in her

career and in the musical lives we (felt we) had spent together: Daniel

Barenboim. He had been in her thoughts all evening—and in her heart. Letting go

is a difficult thing. Like her career, difficult decisions such as ruling

Brünnhilde was not the right role for her included, this was supremely well

judged and directed, as joyful as it was poignant. She never played the

Marschallin, though she had offers; for some of us, at this moment she did.

Life, music, theatre, go on. ‘Tschüss.’

The Klytämnestra we saw and heard was not

the same as that

of 2016 in this same Patrice Chéreau production, nor that (in my case at

the cinema) from its incarnation slightly earlier that year in

New York, still less that of Salzburg

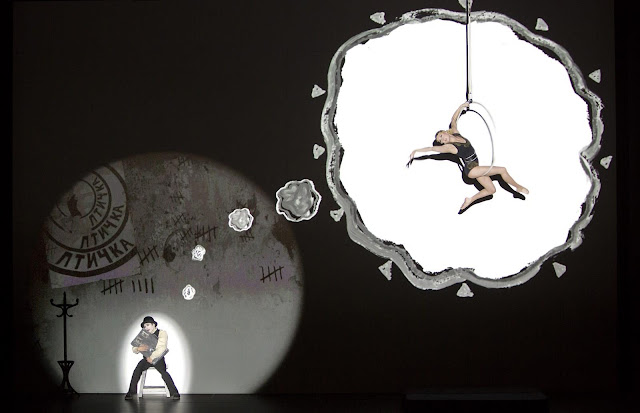

(Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s staging) in 2010. Chéreau’s production remains impressive

in its provision of a frame – literally, in the case of Richard Peduzzi’s set –

for human interactions. Fate can take care of itself. It may or may not be

something more than the sum total of individual characters and their decisions,

but here they are given due weight. And that includes the decisions of those

playing their roles. Perhaps inevitably, in this performance the relationship

between Elektra and Klytämnestra seemed still more central, more crucial than

ever. Yet there was absolutely no grandstanding, indeed little even in the way

of grandeur to it. The Staatskapelle Berlin may have prepared the way for a

grand entrance, or better provided one, for the woman who emerged was a

distressed, even disoriented mother, finding her way according to the text

(Strauss and Hofmannsthal) and acting according to the precept that she

needed her daughter – it was definitely her daughter, not just some other

character – more than the other way around. There was a degree of pride: all

that said, she remained a queen. But this was a queen in private, insofar as

her attendants would ever permit a private sphere to exist, not in public: a

woman compelled to transfer her political wiles to the domestic sphere.

Sometimes she came as close to speech than to song: not because she could not

sing, but rather because she realised she could speak. She held the stage

through artistry, not image; through what she did on this occasion, not through

what she had done in the past.

|

| (c) Monika Rittershaus (2016) |

Ricarda Merbeth’s Elektra offered an

interesting complement, almost a child who retreated into the womb, or rather

who would were it still available. That it was not was a large part of the

problem—at least in this scene. Elsewhere, hers was a performance that lacked

nothing in power yet likewise never forsook the realm of humanity. Vida Miknevičiūtė’s Chrysothemis brought further characteristics of both, as well as

her own, into sharp relief: a portrayal as vividly sung as it was conceived. Lauri Vasar’s dark-toned Orest, brutalised, dangerous,

and yet with more than a hint of his own fragility and neurosis, was similarly

excellent. Throughout a cast that included singers such as Cheryl Studer,

Roberta Alexander, and Olaf Bär, each seemed to bring out something new and

interesting in another.

If Markus Poschner’s direction of the

Staatskapelle Berlin tended often to be fleshing out, even making sense of, a

world created by characters on stage rather than creating it – worlds away

from, say, Daniele Gatti’s Salzburg cataclysm – that seemed in context at one

with this general approach: almost a Kammerspiel. It was certainly not

that the orchestra failed to speak, but not only did it owe as much to

Mendelssohn as to Wagner, it reacted as much as it delineated. The stars, one our inevitable lodestar, may have been on stage but this proved the most collaborative of

dramas. That, surely, was the proper and ultimate tribute. Tschüss.