Leipzig Opera House

|

| Samiel (Verena Hierholzer) and Kaspar (Tuomas Pursio) Images: © Ida Zenna |

Agathe – Gal James

Ännchen – Magdalena

HinterdoblerSamiel – Verena Hierholzer

Max – Thomas Mohr

Kaspar – Tuomas Pursio

Kuno – Jürgen Kurth

Kilian – Patrick Vogel

Ottokar – Jonathan Michie

Hermit – Rúni Brattaberg

First Hunter – Andreas David

Second Hunter – Klaus Bernewitz

Bridesmaids – Katrin Braunlich, Estelle Haussner, Eliza Rudnicka, Teresa Maria Winkler

Christian von Göltz (director)

Dieter Richter (set designs)Jessica Karge (costumes)

Heidi Zippel (dramaturgy)

Verena Hierholzer (Samiel’s choreography)

Leipzig Opera Chorus (chorus master: Alexander Stessing)

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra

Christian Gedschold (conductor)

‘It seems to be the poem of

those Bohemian woods themselves, whose dark and solemn aspect permits us at

once to grasp how the isolated man would believe himself, if not prey to a

dæmonic power of Nature, then at least in eternal submission thereto.’ With

those words, the homesick, indigent Richard Wagner, revolted by what he had experienced

as the base superficiality of Parisian musical culture, reported on an 1841 performance

of Le Freischütz (Berlioz’s version,

with ballet music that was at least Weber’s own). In a piece addressed ‘to the

Paris public’, Wagner ostensibly tried to explain the work to that public, yet

seemed unable to prevent himself from turning his article into an attack upon –

yes, you have guessed correctly – Parisian and, more broadly, French culture.

|

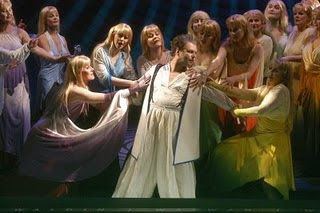

| Kaspar, Samiel and her spirits, Max (Thomas Mohr) |

The Freischütz (most certainly Der) we know and love is the quintessential

German Romantic opera, and Wagner’s advocacy has played no little role in that.

Upon returning to Saxony, to Dresden, he assumed a leading role in the longstanding

if hitherto unsuccessful campaign to have Weber’s bones returned from London

and reburied in the city whose German opera (as opposed to its long-flourishing

Italian version) he had done much to build. Wagner eulogised his predecessor

with music and a flowery address, proclaiming that there had never been a more

German musician. Whilst the younger Wagner had stood far more critical, his

first opera, Die Feen

notwithstanding, of Weber and earlier German opera, now he placed his work in

that tradition, as would others theirs. That is far from nonsense, of course,

yet it is also far from unproblematical. For one thing, it is impossible, living

in the face of what Friedrich Meinecke called in 1948 the ‘German catastrophe’,

to assent to such nationalism any more, however differently it may have been

intended. For another, much of Weber’s music, still more than Wagner’s, and

perhaps still more in this than in Weber’s subsequent two ‘German Romantic’

operas, often questions, even resists, such identification.

|

| Kaspar and Max |

Why do I mention all that?

Because it was very much in that spirit that, almost whether I wished to or no,

I approached this new production of Weber’s opera in Wagner’s home city (itself

long ambivalent concerning its greatest son, its concert tradition long,

somewhat frustratingly, enjoying a higher profile to the fruits of its still

lengthier operatic history). What struck me upon hearing the Overture from the excellent

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Christian Gedschold was, first, how fresh,

how vernal (it had been a beautiful, almost spring-day in Leipzig) Weber’s

score sounded from every section: the strings an ideal combination of the

golden and something darker, the woodwind at times heartbreakingly

characterful, almost as if partaking as woodland creatures in Wagner’s fancy,

the brass as euphonious as one could hope for, horns tender to a degree. And

yet, Gedschold’s direction did not, for me, take its place in the tradition I

think of here as ‘German Romantic’: at least not wholeheartedly, or perhaps it

was my mindset that had me hear it differently. Where Furtwängler, in his

outstanding Salzburg life recording, puts us momentarily at peace, and has it,

perhaps, sound more ‘German’ than the music ‘in itself’ always is, where Carlos

Kleiber somehow makes his objectively hard-driven Dresden account sound equally

at ease with itself, breathing where the tempi might suggest otherwise, this

performance sounded more internationalist, perhaps even more at home with the

French models Weber – and Wagner – so eagerly adopted in individual numbers. (I

mean here a number of the arias and ensemble pieces, although even the Huntsmen’s Chorus, soon to become a

staple of German books of allegedly ‘popular song’, actually derives from part

of an eighteenth-century French street song, ‘Malbrouk s’en va t’en guerre’.)

What sometimes, then, I missed in the seemingly unaffected German Romanticism that

would grow into Wagnerian music drama an aural reassessment of the work as the

number opera it undoubtedly is.

|

| Opening scene |

It

was with such thoughts that I also set about watching Christian von Götz’s

production, in part, I think, on account of his brilliantly

thought-provoking Capriccio, in

which Strauss’s work engaged with its own time to an extent, and to a fruitful

extent, rarely seen. (Such are the perils, as well as the joys, of reception,

whether of a composer, a director, or anyone else!) Perhaps, then, I was too

preoccupied with understanding what I saw as part commentary on German history,

but this is perhaps one of those works in which such a path is inevitable, and

ultimately requires no apology. What struck me from its later

nineteenth-century setting was how it enables, perhaps even invites, one to

consider the work’s Rezeptionsgeschichte.

Indeed, to begin with, I understood it more as a deliberately sanitised version

of the period of composition, the hunting lodge too spick and span, even too

grand (rather as one might visit such a place touristically today, or indeed in

the later nineteenth century). Be that as it may, such sanitisation,

displacement, alienation, however one might consider it, served to remember the

work such as it never was, even if we have ‘always’ known it as such, something

of a ghost, setting the scene for what became still more of a ghost story than

one often sees.

|

| Ännchen (Magdalena Hinterdobler), Agathe, and Samiel |

It is

here, though, a ghost story with a very particular twist, or at least

standpoint. Looking at, if not listening to, Weber from a standpoint not so

distant from Mahler (recall Die drei

Pintos) and his world – the

designs hint as much at Franz Joseph and Bad Ischl as at the Bohemian Woods, at

least until we briefly enter the latter – we begin to understand the centrality

of female experience to the horror tale unfolding. Fear and hysteria reign,

Samiel – here, strikingly, a self-choreographed female dancer, Verena Hierholzer – seemingly a projection

of some evil deed from the past, haunting the present, just as untruths from

our retelling of history continue to haunt us. (Whatever the tribulations of

German history, it is the English who do not have a word for Vergangenheitsbewältigung, resulting

recently in a catastrophe that could hardly seem more likely over here.) Noting

that the opera was originally to be called Die

Jägersbraut, the director plays on Agathe’s fear of marriage, a fear born,

it seems, of living in so unhappy, so haunted, a place. Samiel’s delivery of

the funeral crown in the third act terrifies all the women; is it not, however,

actually the perfect symbol for patriarchal hegemony and the fantasies it

encourages? If the horror-film imagery of Samiel’s other appearances seemed

more silly than anything else, perhaps it is all too easy for a man to say that

in the face of female agency. (I am questioning myself more as Devil’s Advocate

here than because I really think so, but the openness of the staging to such

self-criticism is perhaps not the least of its strengths.)

|

| Max and Agathe |

Such would in itself count for

much less, had it not been for an excellent cast, whose performances would have

graced any stage. If Thomas Mohr, I am afraid to say, looked and acted too much

on the old side for Max – however one might have framed the performance – his

vocal delivery more than compensated. A tenor bright and clear, yet sensitive

too, he complemented very well the sopranos of Gal James and Magdalena

Hinterdobler, exhibiting many of the same qualities, and with fine coloratura

to boot, Hinterdobler’s especially expressive as well as merely impressive.

Tuomas Pursio’s darkly dangerous Kaspar stood very much in the line of other

fine performances I have heard him give (from Wagner

to Nono),

yet there was nothing generic about the malady of his pride and delusion. Jürgen

Kurth and Jonathan Michie offered intelligent, verbally acute performances as

Kuno and Ottokar, whilst Patrick Vogel’s lighter, nimbler tenor (by comparison

with Max) offered ample indication of why he might have won the title of king

of the marksmen. Rúni Brattaberg’s dark, sonorous Hermit did what he should,

although why anyone should necessarily take heed of the character’s words

remains something of a dramaturgical mystery. Choral singing throughout spoke of music well known, 'in the blood', if you will, yet never taken for granted: it was as fresh as it was 'traditional'.

|

| Final scene |

There was then, plenty, of

opportunity to rethink, to reassess, wherever that impulse may have originated.

And yet, for everything I have said, and for all the outstanding quality of orchestral

instruments’ ‘French’ solo moments (of which there are many), it remained the

dark, undeniably Wagnerian tones of the Wolf’s Glen that made the deepest

impression of all. Here, Saxon tradition spoke of an orchestra, one of the

greatest in the world, that knew where this music led, and which was happy to

guide us. Göltz made a better job of staging frankly impossible scenic

directions than many (‘Gothic’ horror notwithstanding), but Weber’s

extraordinary presentiments of Siegfried

remained an aural experience above all. Wagner’s truths may not always be

empirical; that does not necessarily render them untruths.

,+Soula+Parassidis+(liegend).JPG)