Felsenreitschule

Katěrina Kabanova – Corinne Winters

Marfa Ignatěvna Kabanova (Kabanicha) – Evelyn Herlitzius

Varvara – Jarmila Balážová

Boris Grigorjevič – David Butt Philip

Váňa Kudrjáš – Benjamin Hulett

Tichon Ivanyč Kabanov – Jaroslav Březina

Savël Prokofjevič Dikoj – Jens Larsen

Kuligin – Michael Mofidian

Glaša – Nicole Chirka

Fekluša – Ann-Kathrin Niemczyk

Rufus Didwiszus (set designs)

Victoria Behr (costumes)

Franck Evin (lighting)

Concert Association of the Vienna State Opera Chorus (chorus director: Huw Rhys James)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra,

Jakub Hrůša (conductor)

|

| Images: SF / Monika Rittershaus |

For me, Barrie Kosky has often been at his best when staging more serious operas, which do not lend themselves to his trademark ‘showbiz’ treatment, and for which he has shown a single-mindedness again quite different from what other stagings may have led us to expect. Pelléas, Rusalka, Eugene Onegin, and Iphigénie en Tauride spring immediately to mind. Others differ strongly, I know, so it is probably more a matter of taste as anything else (though not in the case of that breathtakingly dishonest Bayreuth Meistersinger). This new Salzburg production of Katya Kabanova broadly falls, I suppose, into that category. There was certainly nothing to object to, nothing to distract; and yet, I could not help but feel—more feel than think—that something was missing.

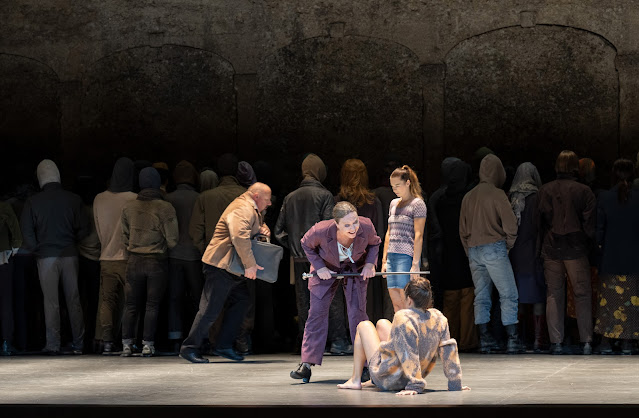

Theatre is not, of course, made in a vacuum. Experience of the pandemic—far from over, of course, whatever our overlords may tell us—is still raw and its consequences are still very much with us (he wrote, typing, FFP2-mask-clad, on a train out of Salzburg). No need to worry: this is not a Katya full of masks, Microsoft Teams, and parties chez Johnson and Simmonds, though surely it will come. (My bet is on a Zoom Tristan by 2025.) But rather, the vast stage of the Felsenreitschule seemed strangely underused, as if to allow for social distancing, save—a crucial exception, I grant—for a vast, immobile (boundaries occasionally altered between scenes) crowd, backs turned to us throughout. Extremely realistic, of all shapes and sizes, this wall of puppets could well have been taken for actual human beings, had one not known—or suspected, given the lack of movement. It was an arresting image, walling in the community, Katya’s horizons, and indeed those of everyone else, although Kosky’s interest, not unreasonably, seemed to lie in the heroine. A large stage with nothing else to detain us: on second thoughts, one could readily have had set designs and kept the characters apart as necessary, so perhaps it was not Covid at all. Words from a programme interview lend credence to that view, Kosky saying that he did not want to ‘do Kátá Kabanova as an Ibsen or Strindberg drama – it’s not just about the family.’ He says he and his production team needed ‘to consider how we could represent this village or small town and Kátá’s feeling of isolation within this place, and at the same time concentrate on Kátá and the immediate family around her, without turning it into a chamber piece with walls, doors, tables, chairs and a samovar – which wouldn’t work anyway in the Felsenreitschule.’

So maybe the pandemic and the horrific loneliness it brought for many of us haunts responses rather than intention; or maybe, just maybe, the one does not exclude the other, especially in the work of so experienced a man of the theatre. For whilst Kosky verbally acknowledged the role of the community, and that puppet-wall was ever-present, the impression—present, I think, in much of the Personenregie too—was of a more existentialist drama than either we are accustomed to or those words imply. True, there were at the beginning of each act other, sonic hints of something, whether natural or social, lying beyond. Birdsong preceded the first act, bells the second, and thunder the storm of the third. Beyond a light bit of sado-masochism, as Kabanicha walked Dikoj around on a leash and poured liquid on him, the abiding feeling for me remained loneliness in a vast space.

In the title role, Corinne Winters proved an estimable contributor to this concept, determined to make her own way in the role, never remotely reliant on post-Hardy (at least for an English speaker) cliché. If I observed and was duly repelled by her treatment, only really at the end was I moved. I say this not as adverse criticism; that seemed to be the dramatic strategy, to emphasise the final breakdown. It seemed to be Jakub Hrůša’s conception too, in the pit. Goal-orientation is not only a musical strategy for Beethoven and his followers. There was never an ounce of sentimentality, never a moment to enjoy the excellent, if not to my ears always entirely idiomatic, playing of the Vienna Philharmonic for itself. Sometimes, I may have wished the music, the drama, would linger just a little, but that was surely the point. And surely they were right.

Where I had a few doubts was with some of the Czech language heard. I cannot really say more than that, speaking not a word of the language myself, but I wonder whether it is a coincidence that, without knowing who they were beforehand, I often felt a greater immediacy from those whose first language it was. First and foremost was Jarmila Balážová: an outstanding Varvara, glowing with an infectious zest for life in such sharp contrast with Katya’s fate and, yes, that of the society around them. Presented with considerable vocal beauty and undeniable sincerity, David Butt Philip’s Boris was another fine portrayal—from an artist who seems never to give anything but. Evelyn Herlitzius gave a duly terrifying star turn as Kabanicha, surely one of the most unremittingly evil characters in all opera. As is her wont, this was a powerfully committed performance throughout. Benjamin Hulett’s idea of Kudrjáš and his communication of that idea seemed almost designed to vindicate the description in Ivana Rentsch’s excellent programme essay of his character’s ‘mellow detachment’, as much expressed through sonority as gesture.All contributed, though, to the sharply delineated drama unfolding; there were no exceptions, nor even weak links. And whether the pandemic coloured conception, response, or both, is perhaps unimportant, given the tragic power of the denouement.